Comment: How Shell and BP’s tar sands plans went wrong

Dozens of projects in the Canadian tar sands have been put on-hold, delayed, or cancelled in the last two years, according to a new report by Greenpeace and Oil Change International.

Among these 42 projects is the Shell’s cancelled Carmon Creek project, and postponed phases of BP’s Sunrise venture.

Amid the rubble of their once much greater plans for Canada’s tar sands and whatever else they may claim, BP and Shell can’t say they weren’t warned.

In 2010 BP and Shell casually dismissed shareholder concerns about the assumptions underpinning their Alberta ambitions about fundamental issues such as long term oil price stability, Indigenous groups’ and local community opposition, and increasing regulation on GHG emissions.

Fast forward 6 years and such shareholder concerns have been vindicated.

After its balance sheet adjusting cancellation of Carmon Creek, Shell’s remaining plans for expanding its tar sands operations have moved into the realm of mere “ideas” according to CEO Ben van Beurden.

And despite BP claiming as recently as December 2014 that all three of its projects were growth opportunities to 2020 and beyond, Bob Dudley stated in April 2016 that “[BP] have one oil sands project. It is very questionable whether we’ll have any more”.

It would be easy to disregard BP’s and Shell’s stunted tar sands ambitions as the temporary and manageable consequence of a volatile oil price.

But to do so would be to miss the worrying signposts this reversal of fortune provides for the oil industry’s future.

It’s vital that the correct lessons are learned by the companies and their investors, for they extend beyond the tar sands to the very heart of the oil majors’ high-cost, frontier driven growth model.

Not just the oil price

Despite mainstream commentary, the swathe of cancellations and delays is not solely due to the fall in oil price but also to a number of other factors including lack of pipelines, increasing political action on climate and Indigenous community opposition.

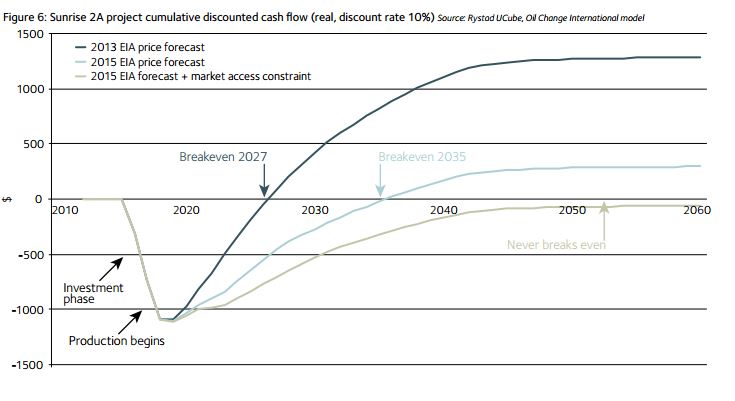

Of the 27 cancelled/postponed projects assessed, the report found that 14 – including BP’s Sunrise and Shell’s Carmon Creek – have been rendered uneconomic by the combination of 2015 oil prices and the additional cost of rail (arising from the absence of pipelines).

These projects are associated with over 60% of the reserves held in all 27 projects.

If no new pipelines are built there will be no pipeline space available for tar sands production growth beyond that which arises from the projects already under construction.

After the rejection of Keystone XL and Prime Minister Trudeau’s opposition to Northern Gateway there are only 2 remaining new pipeline proposals: Kinder Morgan and Energy East – both of which face significant opposition.

Energy East suffered a significant setback yesterday and some analysts rate its chances of proceeding at only 25%:

High costs

Even with a pipeline, break-even prices BP’s and Shell’s potential future projects are so high that while it is not implausible that oil prices could reach such a range in the coming years the projects would carry high risks of making losses if those prices do not persist:

Aside from the outliers of the cheaper Pike 1 and Terre de Grace pilot and the expensive Jackpine projects, BP and Shell’s future projects generally have break-even prices in the range of $75- 85, even if the Kinder Morgan pipeline is built.

This is significantly higher than the vast majority of the world’s proven oil reserves.

If forced to rely on rail, the projects’ economics become even more stark.

Apart from Pike 1 and Terre de Grace pilot, the breakeven price range increases to $95-110 – around the levels reached during the high price years of 2008-14.

Next stop: the Bight

The tar sands are the poster child for all that is wrong with the oil major’s business model: High-cost, technically challenging, long-life, vulnerable to climate policy, and vehemently and often physically opposed by Indigenous people and local communities.

Investors need to urgently rein in capital allocation to high-cost frontier projects or face the prospect of the current fate of the tar sands becoming the template for the industry.

Yet BP’s decision to head to the unexplored and ecologically significant Great Australian Bight suggests that it has not learned any lessons from the demise of its tar sands ambitions.

Louise Rouse is an investment campaign consultant to Greenpeace UK