Fracking in the UK (update 2)

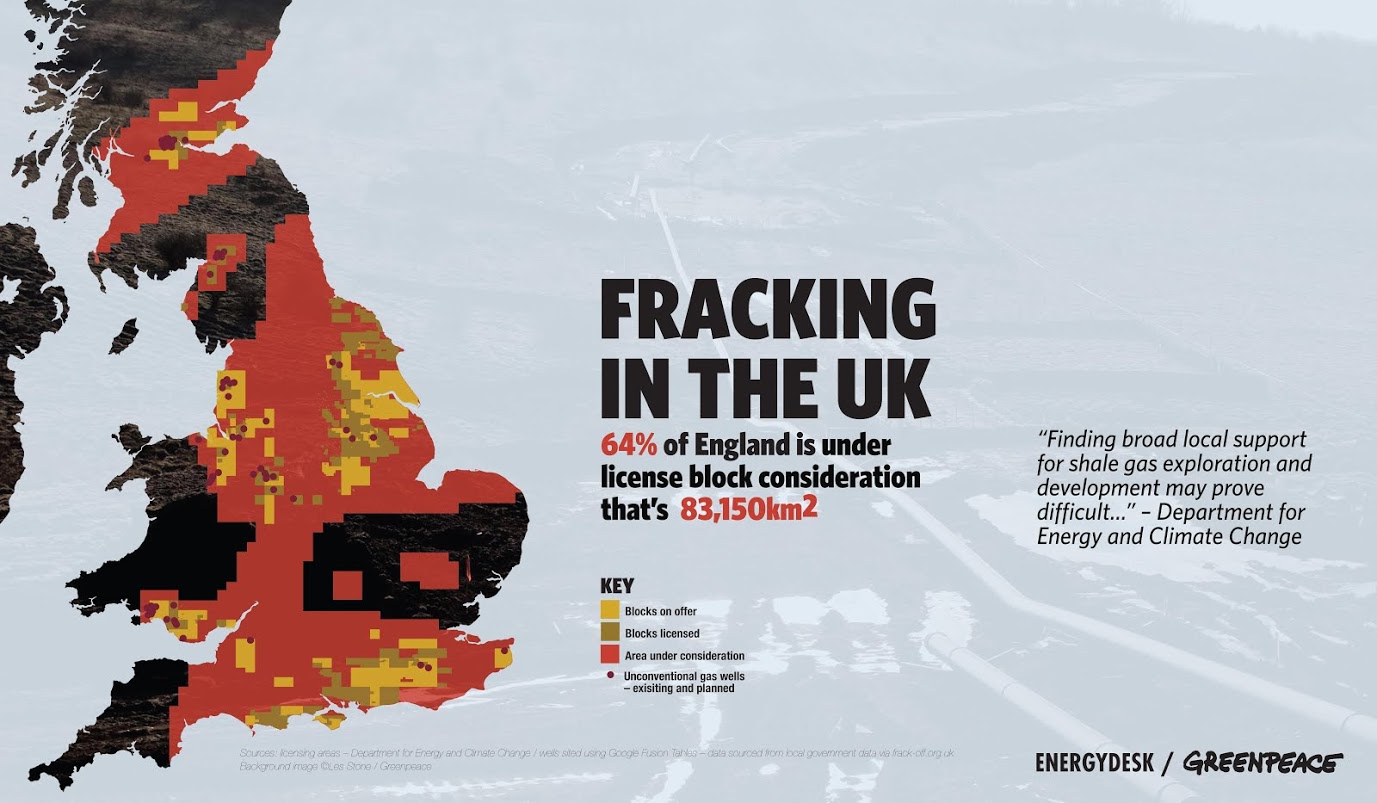

The map shows the land area either currently licensed to a fracking operator, up for license or included in the delayed 14th licensing round currently under consultation by DECC.

Most of the area highlighted in pink remains under consultation, with licensed blocks in the South East, South West, North East and North West under DECC’s previous, 13th round.

The 14th round, however, has been delayed – meaning that though much of the UK may be licensed for exploration its impossible to say how much shale there is, or how much fracking may take place.

The issue of the 14th round was raised by Nigel Smith, Seismic/Basin Analyst from the British Geological Survey (BGS) who told MPs earlier this month:

“I think one of the problems (with establishing the scale of the UK’s resource) is we have had the 14th round of licensing delayed. If that had been enacted, lots of companies would have taken out licences, probably covering most of the country.”

Whatever is found the map also shows how relatively few license blocks are likely to prove geologically feasable or socially and environmentally acceptable. The gas price will also play a major role.

The data doesn’t suggest that 64% or even a fraction of that area will actually be exploited for shale.

As a statement from the Department of Energy and Climate change made clear,

“There is a big difference between the amount of shale gas that might exist and what can be technically and commercially extracted.

“It is too early to assess the potential for shale gas but the suggestion more than 60 per cent of the UK countryside could be exploited is nonsense.

“We have commissioned the British Geological Survey to do an assessment of the UK’s shale gas resources, which will report its findings next year.”

What it does show is that the parts of the country which could be subject to exploration – including some test wells – are far larger than previously thought.

The analysis – and it’s illustration – has provoked criticism from some who argue it will only reinforce existing opposition to a range of measures, including wind power.

“The stat is designed to provoke defensive nimby opposition and raise political costs associated with shale gas – not to do anything that might help the climate,” said Michael Davis, commenting on the article.

How we worked it out?

The map was calculated by taking data from DECC’s 13th licensing round and overlapping it with Figure 2 in this DECC document, highlighting their 14th round consultation – which is far larger.

We then used local authority data obtained by a bot used by anti-fracking group, Frack Off to scan planning applications and so provide up to date information on applications for unconventional gas drilling.

That data is available via a Google fusion table and includes all the company and local authority information.

It should be noted that a large number of these sites (for drilling) are coal bed methane – which is different to shale gas fracking. The distinction is made clear in the table.

The 64% figure was calculated rather simply by adding up the land area available for fracking under the DECC data and calculating that as a proportion of England’s land area. It’s also pretty clear from the map.

What it means?

The data makes clear that licenses for the extraction of shale gas have been granted or made available throughout the South East, South West, Midlands, South Wales, North East and North West.

In fact one of the largest conurbation’s of granted licenses is around London and the commuter belt including the Sussex village of Balcome where residents have voiced strong opposition to plans by Cuadrilla (who started drilling in Blackpool) to drill for shale there.

However, the data doesn’t mean that a fracking rig is about to be assembled in your back yard – even if you reside in one of the areas under license.

To begin with those areas that are not licensed or are simply under consultation may never be bought up.

They simply correspond roughly to geological formations identified by the British Geological Survey (BGS) and identified in their report for DECC.

Even those area’s which have been bought up – and we’ll be publishing more about who owns what in future – may not lead to drilling.

Shale gas drilling in the UK is currently suspended, until wells are drilled (Cuadrilla currently has three near Blackpool) it is extremely hard to know the scale and availability of any resource.

As Mr Smith put it in his evidence; “It has taken Cuadrilla three years to get to the stage of drilling and getting a result, even if they have not published fully what we need.”

So someone will have to drill some ‘test wells’ in your area before you know whether you are going to carry on as usual or unwittingly find yourself in the midst of a great shale gas bonanza.

The evidence suggests that the British public, not known for it’s appreciation of countryside development, isn’t enamoured with the idea.

Indeed a recent opinion poll found 11% of the British public would support the development of a shale gas well near their home.

As Michael Liebreich, chief executive of Bloomberg New Energy Finance, put it recently

“The British public does not like onshore wind-farms near their homes. But then they do not like roads either. Or chemical plants. Or nuclear power stations. Or sewage treatment farms. Or homeless hostels. They are going to love fracking operations. ”

But that said, not everyone may see it that way.

Horizontal drilling has significantly reduced the number of wells needed to extract gas from shale and, in the US at least, drilling has become part of every-day life. They even drill under Dallas Airport. Some have argued that a drilling rig is less obtrusive than a wind turbine.

It may also prove hard for environmental groups – such as Unearthed owner Greenpeace, keen to promote wind power, to object to shale on grounds of the industrialisation of the landscape.

But then, in the US, you own the shale under your feet in the UK its owned by the state. It’s a small difference in law, likely to lead to a big difference in public acceptability, unless the Chancellor can make the case it will lower bills.

So we have lots of shale then?

No. We simply have lots of areas which DECC plans to license to companies looking for shale. There is fairly big difference.

More reserve estimates are expected over the next twelve months but by current estimates of extractable UK reserves is that there is between 20 and 40 trillion cubic feet of gas available for extraction.

It sounds a lot, but it works out at around 4 years at our current rate of consumption. Because it would not all be extracted at once it would not be sufficient to end our gas imports.

Which is probably lucky – for those who fear excessive development. A back of the envelope calculation by Bloomberg’s Mr Liebreich leads him to suggest that,

“In order to replace the decline of U.K. Continental Shelf gas production through 2030 you would need 2,400 fracked wells.”

“This number,” he adds, “would extend over an area the size of Lancashire.”

Perhaps it would, but they would likely never be drilled, or perhaps technology would change.

Either way, once the Chancellor fires the starting gun, we’ll finally get to find out.