Q&A: What does the TTIP trade deal mean for energy?

The Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (known hereafter as TTIP) , which is currently in the process of being negotiated may sound obscure – but it could have a big influence on how Europe meets its energy needs.

The deal could facilitate imports of shale gas from the US and Tar Sands from Canada, but it could also have far reaching impacts on Europe’s environmental regulations, effectively harmonising them with the US.

The negotiations, which take place behind closed doors, were launched last June and there have only been a few rounds of talks since then. The next EU-US summit on the topic will be held in Brussels on 26 March, which will be Obama’s first visit to the Belgium capital.

An initial EU position paper argues the World Trade Organisation “does not fully reflect issues” related to energy generation and trade, and that TTIP could provide stronger rules for the sector.

The trade agreement between the US and Europe could have wide-reaching impacts on how environmental regulations are written – and may already have influenced the Commission’s 2030 energy and climate package published last month.

There might also be a specific chapter on energy as part of the deal. The EU wants this text on energy, while the US is resisting this, reportedly.

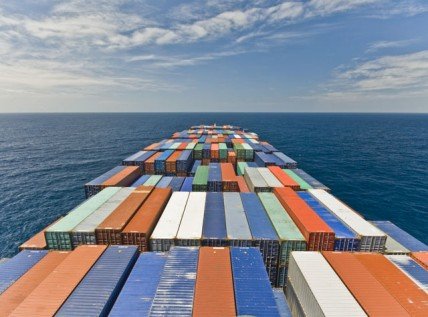

Whether it is through the main text of the agreement, and/or an energy chapter, TTIP could affect the energy sector by opening the door to the import of oil from US and Canadian tar sands (through the US) and imports of shale gas in the form of LNG (liquified natural gas). The EU highlighted that the new rules should adhere to the “fundamental principles of transparency, market access and non-discrimination”.

TTIP could also see European fracking regulations stymied.

And it’s all highly speculative at this stage, but all this could have knock-on effects to Europe’s energy mix.

But hang on, let’s go back to basics. What is TTIP and why do the EU and US want it?

The point of the deal – touted as the biggest in economic history – is to “liberalise trade and investment” between the regions. Put simply it aims to get rid of “trade barriers in a wide range of economic sectors to make it easier to buy and sell goods and services between the EU and the US”.

The EU and US generate 40% of global GDP and more than $2.2 billion of goods and services traded every day across the Atlantic.

One of two main ways the deal would work is by ’harmonising’ regulations that are considered to have an effect on trade. Proponents of the agreement argue10-20% of the cost of imported goods lies in dealing with bureaucracy, so removing red tape will help trade. But NGOs are highly concerned that cutting regulations, including environmental ones, could have detrimental effects.

A second mechanism would be to remove import tariffs – which were only 4% on average anyway – to make goods imported from the US cheaper in Europe and vice versa.

If signed, the Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) estimates global GDP would increase by €310 billion. A report for trade directorate predicts EU’s GDP will increase by between 68 and 119bn euros – EU Commission president Barrosso uses the 119 figure, which is around 1% of the EU’s GDP.

But, as the FT explains, it is difficult to quantify the benefits of trade deals, and figures are often exaggerated.

The European Environmental Bureau (EEB) say that the economic gains from TTIP are more uncertain than they appear.

It questions whether the impact assessments carried out by the EC complies with the Commission’s internal standards for these kinds of studies, and says “these figures are the result of a limited modeling exercise using highly unrealistic assumptions about levels of removal of Non Tariff Barriers (NTB) – without assessing the benefits such ‘barriers’ bring in terms of protection public health, environment or workers’ rights.”

So harmonising regulations is very significant. What does it mean?

EU trade commissioner Karel de Gucht speaks of ‘mutual recognition’ of standards.

In practice it will mean a set of rules and procedures to ensure closer regulatory co-operation or coherence. And the EU has proposed the establishment of aRegulatory Cooperation Council (RCC) to deepen regulatory co-operation.

One possible consequence is Europe having to lower the bar for its regulations, including environmental ones.

It could be that to create a level playing field between the EU and US, the EU’s long-established precautionary principle – which “presupposes that potentially dangerous effects deriving from a phenomenon, product or process have been identified” even where the science is uncertain – could be at risk because often the US’s standards are lower.

EU negotiators acknowledge that “the EU relies more on regulations” whereas “the US [relies] more on litigation”.

However, the EU has vociferously defended its backing of strong regulation stating “there will be no compromise whatsoever on safety, consumer protection or the environment. But there will be a willingness to look pragmatically on whether we can do things better and in a more coordinated fashion.” We’ll see.

So that’s how TTIP might affect regulation on a EU level – but what about individual countries?

TTIP may include a provision for multinational firms to be able to legally challenge member states’ laws, precipitating a deluge of environmental lawsuits. According to a draft document seen by Unearthed, TTIP could include similar parameters to the leaked Canada-EU trade agreement (CETA) which describes “legitimate expectations” of profit and “fair and equitable treatment” for investors.

The Canadian agreement is further along having been signed but not made public yet. A similar clause in the North American Trade Agreement has given rise to energy firm Lone Pine challenging a fracking ban in Quebec, Canada introduced in May 2013 in a $250m lawsuit.

Late last year, trade commissioner de Gucht said TTIP could include an‘Investor-State Dispute Settlement’ process.

The investor-state mechanism has proved so controversial that in late January the EC announced it was postponing talks on the topic with a view to launching a public consultation. Less than a week later the Commission launched a new advisory group with stakeholders to give input into all aspects of the TTIP talks.

The Greens in European Parliament called the clause a “massive Trojan horse”that could whittle away EU environmental standards and regulations, among others.

Is TTIP already having a chilling effect on EU regulation?

It’s possible. The regulation of unconventional fossil fuel extraction – including shale gas and tar sands – has been among those listed as a “technical barrier” to trade by those pushing for the TTIP deal, according to European Environmental Bureau.

This means the regulatory co-operation and investor-state dispute settlement provisions could come into play, as they relate to the aim to eliminate or reduce technical barriers to trade – assuming they are in the final deal.

Pieter de Pous, EEB’s policy director, who will represent the organisation at EC’s TTIP advisory group meetings, told Unearthed: “US and Canada have indicated they want to sell [unconventional fossil fuels] to the EU market… Tar sands and shale gas are probably some of the biggest drivers of TTIP from the US side.”.

What’s been going on in the case of tar sands trade?

In its 2030 energy and climate package, the European Commission killed off the Fuels Quality Directive post-2020 with the words: “The Commission does not think it appropriate to establish new targets for renewable energy or the greenhouse gas intensity of fuels used in the transport sector or any other sub-sector after 2020.”

The current directive requires EU fuel producers to reduce the carbon intensity of transport fuels by 6% between 2010 and 2020, and in theory limited imports into Europe of high-carbon fuels such as Canadian tar sands oil via US refineries. The export of crude oil and refined products derived from tar sands could raise the carbon intensity of Europe’s fuel stocks by up to 32.5 million metric tons annually from 2020, a recent report said.

In reality the FQD hasn’t been implemented yet, but the lack of a post 2020 target appears a concession to Canada and the US, which have lobbied hardagainst anything blocking a trade in the fuel.

A Brussels-based source suggested the looming TTIP negotiations were probably a further disincentive to extending the FQD.

There appears to be conflicting evidence on this: US trade representative Michael Froman denied that TTIP was a tool for deregulation but has also said:“I share your concerns regarding the EU’s development of proposals for amendments to the fuel quality directive… We continue to press the Commission to take the views of stakeholders, including US refiners, under consideration… We are seeking through the TTIP negotiations improvements in the EU’s overall regulatory practices.”

The minutes of the last-minute 2030 energy package negotiations confirmed trade was one of the key issues in the line that effectively squashed the FQD post 2020, noting “the need for a cautious approach because of the possible impact on international trade”.

What about shale gas?

Fracking regulations are quite different in the US and EU.

Without TTIP there have already been lawsuits aiming to break down fracking bans such as the one in France, these kinds of actions could become more likely and more successful with a deal – based on the Lone Pines example in Canada.

Also, if in the future the EC wants to introduce a legislative proposal on fracking in the EU, rather than the guidelines released in January, the line on closer US-EU co-ordination could mean having to consult with the US before doing so.

De Pous told Unearthed it’s all highly speculative, but TTIP could also open the door to shale gas LNG imports. He said this could be “Politically the single biggest detraction from high energy savings, high renewables policies that present better and cheaper alternatives for resolving energy security issues.” It could also further encourage countries to develop their own shale reserves, he said.

How likely are these LNG imports from fracking in the US? And what impact could they have?

Hardly any LNG is leaving the US yet, but deals have already been signed which could see shale gas imports in future – even without TTIP.

TTIP could make this easier, according to an analysis by Washington based think tank the Brookings Institution. It says US gas exports could be around 170 million cubic metres per day, which is half of the UK’s daily demand in winter, by 2020.

But there is a question mark over how cheap this LNG would actually be after the costs of liquifying the gas, transporting it and then re-gassifying it are taken into account.

Infrastructure is another barrier as there are a limited number of LNG import terminals in Europe – two are in the UK and Spain. Also, large amounts of LNG imports would create the need to reverse the flow of LNG – from Russia in the east to expert terminals in the west. E3G energy analyst Jonathan Gaventa told Unearthed this would involve a significant build-out of infrastructure in Europe.

In a 2012 report the International Energy Agency said it expects US gas to play a larger role in the EU energy market but for dependence on Russian gas to continue.

In terms of the impact of shale gas LNG imports in the EU energy market, Gaventa llikens it to “reading tea leaves”.

A lot hinges on the quantities of LNG that is imported. If it’s only small quantities, it might not affect the price of gas in Europe that much. “But large quantities might change the dynamics of the market and increase political pressure to try and re-negotiate Russian gas contracts,” Gaventa says.

LNG imports will mainly be competing with other sources of gas or coal, and may just end up displacing other sources so the net effect on gas prices could be neutral, while large quantities of coal-to gas-switching could depress coal prices, he added.