Questions & answers on Ukraine crisis and energy in Europe

Russia has finally acted on its threat to stop the supply of gas to Ukraine, following Russia’s gas giant Gazprom raising the prices for Ukraine by 44% and protracted discussions over Ukraine’s energy bill.

This has happened amid escalating tensions between Russia and the West over the Crimea crisis – and reports in the media of renewed discussions around a 2030 energy savings target (read more below).

What does it mean for gas supplies to Ukraine and Europe? In the short-term, probably not much as both have gas in storage and it is summer.

Why does this matter?

Around 30% of the EU’s gas – 130 billion cubic metres in 2012 comes from Russia with around 15% of the gas imports flowing through Ukrainian pipelines.

In 2011 Bloomberg reported Russia’s gas sales to Europe were worth $57bn of which around $31bn went to Europe excluding Turkey.

In total the EU spent 545bn euros on energy imports in 2012 (421 bn in net terms) with Russia the largest exporter to the economic bloc, accounting for around a third of coal, oil and gas imports in 2010.

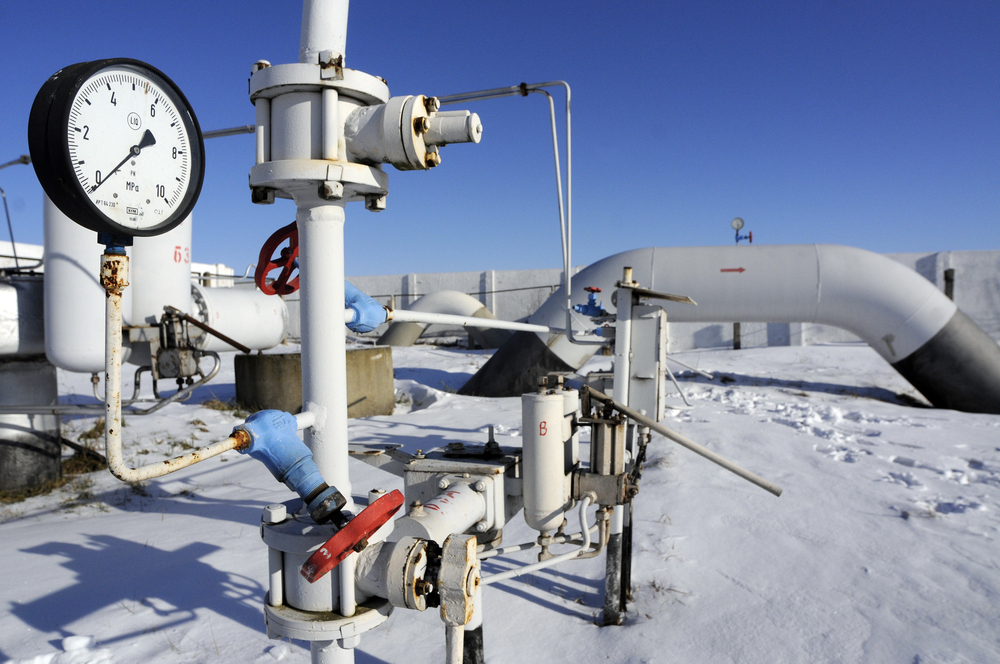

If the Kremlin do turn off the gas taps, some countries in Europe will be more affected than others, as you can see in the below graph from ING Bank analysts.

Countries in central and Eastern Europe are the worst hit, with Hungary and Slovakia relying on Russia for around a third of their energy. But the UK and Spain directly received almost nothing from Russia according to the 2012 figures, and Germany imported around 8% of its primary energy from Russia(working out at 36% of its gas imports).

Gazprom claims countries such as the UK could be indirectly buying as much as15% of its gas from Russia via other countries such as Germany. EU gas production is also falling with Denmark becoming a net importer last year due to declining production of oil and gas from the North Sea.

With EU gas storage at record levels – thanks to a mild winter – analysts are split as to how long Europe could withstand a complete Russian cut off with parts of Eastern Europe potentially struggling with supplies.

Is Russia likely to stop the supply of gas to Europe?

In January 2006 and 2009 Russia cut off gas supplies through the Ukraine causing a short term spike in EU gas prices, but apart from that Russia has beena reliable supplier.

But only some of Russia’s gas now flows through the Ukraine and Russia turning off the taps completely remains unlikely. On the Russian side of the equation, it seems it would be disadvantageous to stop its gas supply to Europe while oil and gas revenues make up around half of Russia’s state income and around70% of its exports are oil and gas. As German chancellor Angela Merkel observed, Russia exported gas to Europe even during the height of the cold war.

Also, there are more transport routes into Europe available now.

What is being proposed?

Various solutions have been touted by political leaders as the solution to the EU’s energy security.

In the medium term EU leaders are currently in the process of deciding over the next round of energy and climate targets – which could include cuts in gas use through energy efficiency and renewable energy.

However leaders are also discussing ways to substitute Russian gas for other fossil fuels, though most of these are difficult or expensive – otherwise we’d do them already.

For instance, EU officials asked US president Barack Obama to help with the supply of LNG (liquified natural gas) from shale gas from over the Atlantic on 26 March – LNG export infrastructure would need to be built.

The Polish prime minister Donald Tusk has urged the ‘rehabilitation’ of coal in Europe, as well as fracking, LNG imports and an EU energy union to negotiate for gas if Russia turns off the supply. Poland already sources more than 80% of its power from coal but much of its heating comes from gas.

Meanwhile, in the UK the prime minister David Cameron has argued fracking is the answer to the energy security issue, and Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel has advocated for fracking – however her Social Democrat environment minister recently called for it to be made effectively illegal.

Is LNG really an option?

In theory, yes. European Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) terminals can import as much as 199 billion cubic metres of gas a year. This is more than we currently import from Russia. And as a result of the Crimea crisis, shipped LNG imports could rise.

The political focus mainly on the US, which is planning to increase exports of shipped gas. The EU is currently working on a trade deal with the US which could pave the way for imports as well as harmonising environmental rules between the two economic blocks.

But LNG exports could see further fracking and/or higher gas prices in the US as a result. It would also would require new LNG terminals and pipelines to be built on both sides of the Atlantic, and for European countries the LNG would be expensive compared to Russian gas. Even if the economics made sense, US gas wouldn’t arrive in Europe for a few years.

Because of these issues, Qatar and North Africa – which also present geopolitical risks – are more likely export partners in the short term. Natural gas prices in Europe would have to double, however, in order to replace Russian gas with LNG from around the world, according to Bloomberg. The global market for gas is very competitive with Asian countries also increasingly vying for gas imports, such as Japan and China.

Another barrier to this possible solution is that in Europe the terminals and pipelines are not necessarily in the right places to get gas to all European countries, especially in the case of a prolonged Russian shutdown. EU storage could last a few months but after that it would get more complicated.

How about coal?

Another option could be to switch from Russian gas to coal – but obviously this is not great in terms of preventing catastrophic climate change.

To an extent this is already happening. Low carbon prices and relatively high gas prices in the past five to six years mean that Europe is burning more coal for power, largely at the expense of gas – making it hard for the EU to switch even further from gas to more polluting coal.

But a study by the German Frauhnhofer institute and a separate report by the UK government both suggest that new hard coal plants would be more expensive than onshore wind today. In future we are likely to face rising costslinked to the carbon emissions they produce.

And there is another, more fundamental, problem. Russia also exports coal to Europe (about 27% of EU demand) – with significant amounts going to both Poland and Germany, the two biggest consumers of coal in the EU, as well as the UK.

How about fracking?

Fracking is basically an unknown quantity right now with more reports written then exploratory wells drilled.

The early evidence suggests while it could provide some gas it would be too expensive, and too little and too late to have a major impact on Russian imports to the EU.

An industry backed study by energy consultants Poyry into European shale gas suggests supply will come on stream at scale in around a decade.

It also argues that by 2030 exploiting shale would provide less gas than Russia does today, reducing the EU’s gas import dependency by up to 10-18%.

The think-tank E3G echoes these concerns about the relatively small quantity of gas fracking in Europe could supply, noting: “Even under the most optimistic scenarios, shale gas is projected to meet just 10% of European gas demand by 2030. Most commentators agree that 2-3% by 2030 is a more realistic estimate.”

Indeed even if the most optimistic scenarios are realised the Poyry study notes that even a shale boom will have no impact on Russian imports until after 2030 because shale gas will be more expensive than Russian imports.

As Poyry’s shale gas report author told The Guardian: “There’s nothing in that level of shale gas production that will reduce the dependence on Russia from where we are now. In fact it would still be increasing over time. What you’d need to do, instead of looking at increases of shale gas production you would need to start trying to introduce more energy efficiency measures.”

A 2013 Ernst & Young report said “A shale gas boom in Europe could, in practice, weaken energy security in Europe through over-reliance on a single energy source.” Security of supply could be achieved through diversity of supply sources, it added.

And nukes?

Currently, 44% of European reactors are older than 30 years and need to be taken out of operation, since extending their lifetime represents a safety risk and increases costs. Meanwhile, the three nuclear reactors under construction in Europe – in Finland, France and Slovakia – are overshooting their budgets, and experiencing technical problems and suffering extended build times.

In terms of energy security, almost all of the uranium for nuclear in Europe comes from outside of the EU – 27% of which comes from Russia. Niger, Kazakhstan, Australia, Canada and Namibia are amongst other major exporters.

Can efficiency and renewables cut gas imports?

An alternative is to cut back on fossil fuels and subsitute them for other forms of energy.

The current crisis comes as EU leaders are set to decide on the next round of climate, energy efficiency and renewable energy targets up to 2030.

The combination of increased energy efficiency – the only tool able to deliver rapid cuts in gas use – and an increase in renewables uptake – already the fastest growing power source in the EU – will reduce natural gas use in Europe.

According the the European Commission’s impact assessment strong and binding renewable and energy efficiency targets could result in around a 28-29% reduction in natural gas consumption in Europe (see chart).

Whilst all the scenarios would reduce gas use, a more modest greenhouse gas target – without renewable or efficiency targets – could have a very limited impact with EU coal plants closing and being replaced by gas plants rather than cuts in energy use or clean energy.

A 2012 study commissioned by FOE shows the EU could save €200bn through efficiency measures while the roll out of renewables would decarbonise the power sector as coal plants shut down.

The Commission has recommended a 40% cut in domestic carbon emissions and a binding EU-wide target to increase the share of renewables to at least 27% by 2030. The Commission has excluded setting national renewables targets and has in the past delayed discussions on an energy efficiency target pending an ongoing review.

However, now the Ukraine crisis has put a robust energy efficiency target – of 30-35% less fuel used in 2030 than projected – back on the table. The push for the new target is being led by Germany – a major player in EU politics as the largest economy in the bloc – and Denmark.

A 25% efficiency saving target is expected to reduce EU gas imports by 9% by 2030; a 35% target would cut them by 33%; and a 40% target by 40% (the renewables target remained static for the purposes of the comparison), according to a draft figures in a European Commission analysis.

Green NGOs have called for an at least 55% GHG reduction, 45% renewables and 40% energy efficiency targets as part of a push for 100% renewable energy.

What about more (and better) interconnection?

It’s possible to get 77% of Europe’s electricity from renewable sources by 2030 through smart grids, demand management, gas backup and big changes in how our power grid works – according to a recently-published analysis by consultants Energynautics for Greenpeace based on European weather information for 2011 and data from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The model suggests that by taking a pan-European approach rather than planning by country and using a relatively new type of power cable the cost of integrating new renewables into the grid can be significantly cut.

This means you can meet three quarter’s of Europe’s power from renewable sources for slightly more than countries are currently planning to spend on grid upgrades delivering just 37% renewable power.

Updated 17 June 2014, first published 6 May