How Brazil’s giant dam programme could actually increase emissions

Balbina Dam reservoir

Large hydroelectric power projects may be contributing to global warming – rather than helping to reduce greenhouse gas emissions – due to grossly underestimated methane emissions from dam-created reservoirs flooding forests, according recent research.

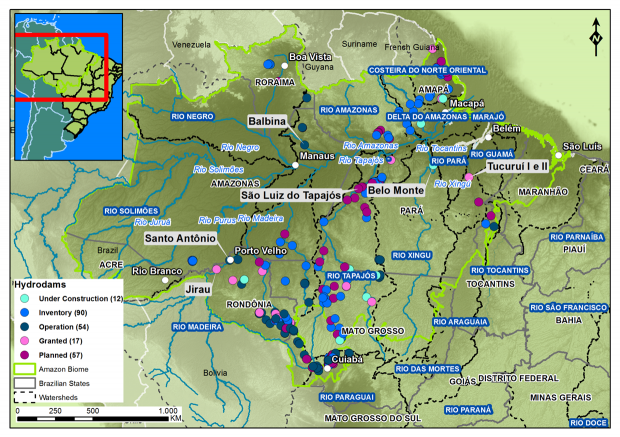

This could have serious ramifications for countries such as Brazil – which is in the process of building 12 dams on tributaries of the Amazon and has another 218 proposed.

The controversial Belo Monte dam, under construction, is the best-known of these – and current president Dilma Rousseff’s popular predecessor Lula Inacio de Silva declared the project would go ahead “na lei ou na marra [by fair means or foul]”.

A run off for Brazil’s presidential election will take place on 26 October – with Rousseff looking likely to win and continue championing the development of infrastructure projects, including dams. She has implemented more infrastructure projects during her presidency than at any time in Brazil’s history.

The problem is that until recently the emissions linked to dam projects – which largely come from methane – haven’t been properly measured.

Methane emissions from tropical “drowned forests” higher than expected

The first study to quantify methane released from dam reservoirs, published in Biogeosciences in August, concluded the amount of methane emitted from tropical reservoirs during their first years of operation “has most certainly been underestimated until now”.

The researchers monitored emissions from the NamTheun 2 reservoir in Laos – the largest in southeast Asia – finding a type of methane emission called “ebullition” was not fully accounted for.

Ebullition happens when bacteria break down organic matter in areas of flooded vegetation, which gives rise to large methane bubbles that rise up from the bottom and burst at the water surface.

The study showed that ebullition accounted for 60% to 80% of total methane emissions from the reservoir in the first few years following filling.

Filling reservoirs in tropical areas of Asia, South America and Africa can create “drowned forests”, which could be emitting over 10% of man-made methane around the world, say the researchers from French National Centre for Scientific Research – though in areas of low vegetation such as Iceland, hydro is a net benefit to climate change.

Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas, 84 times more warming than CO2 over 20 years according to the IPCC. That means if Brazil goes ahead with its programme of building large hydro dams, this could create a massive impact on the climate.

Map: Geolab Greenpeace Brazil

Map: Geolab Greenpeace Brazil

Belo Monte – a mega operation that will be the third-largest dam when it is fully completed – continues although an appeals court judge that the dam was unconstitutional in a 2012 ruling because of lack of consultation with the public – though this was overturned. Its construction has displaced 20,000 indigenous villagers.

The dam could now also be an imminent threat to the climate. The reservoir has now been filled and the water is at 97 metres above sea level, flooding 250 square miles of the Amazon forest – the world’s largest and arguably most precious carbon sink.

One concern is that because of the seasonal variation in water levels in the Amazon region, Belo Monte could be the most inefficient dam ever built hitting 10% of its theoretical maxiumum output of 11,233MW during the dry season and an average of only 39% of its nominal capacity throughout the year.

At a total cost running to over $14.4 billion, majority funded by the Brazilian Development Bank BNDES through loans to the public-private partnership known as the NESA (North Energy plc) Consortium, Belo Monte is looking economically risky.

Aerial view of the Belo Monte Dam construction site

Aerial view of the Belo Monte Dam construction site

Political will

Political support for the dam project remains – with little apparent interest in stopping emissions.

Marina Silva, former environment minister and green candidate has dropped out the presidential election. In spite of Silva’s work in bringing environmentalism –and an understanding of the ecological dangers of large reservoirs in the Amazon – into the heart of Brazilian politics, both main parties are expected to push ahead with building hydro dams as a sign of Brazil’s progress.

The PT, who are most likely to win, have promoted a model of developmentalism that has been less focused on environmental sustainability than large taxpayer-funded industrial projects, of which Belo Monte is the biggest.

Without the political will in Brazil to fund and implement mitigation strategies immediately, it seems increasingly likely that the continued industrialisation of the Amazon for hydroelectric dam building may become an unexpectedly devastating contributor to climate change.