Factcheck: How to clean up an Arctic oil spill in four steps (and why it is unlikely to work)

UPDATE 17/6/2015: Shell’s spill response plan has been approved by an appeals court, after environmental groups challenged the its initial approval by the US government. The court held that stating that 10% of oil “will escape primary offshore recovery efforts at the blowout” does not mean that Shell claims to recover 90% offshore. The court’s view is that Shell is stating 90% will remain offshore but that Shell makes no claim as to how much oil it will actually recover at a blowout.

After a two-year hiatus Anglo-Dutch oil giant Shell is returning to drill in the frozen north, but what will happen if things go wrong? We’ve decided to take a look at the firm’s relatively little known spill response plan (see full Greenpeace analysis here).

The firm says that any spill could be contained – indeed 95% of it would be cleaned up – the problem is the plan appears to depend on equipment which hasn’t been tested and the weather holding out — even if everything else goes perfectly.

No company has successfully drilled for oil in the ice-covered and inhospitable waters of the Chukchi Sea, and Shell’s plan is nothing if not ambitious.

“Based on past experience, 95% recovery is very optimistic. To my knowledge, such recovery has never been accomplished, “ said Robert Bea, an engineering professor at the University of California, Berkeley, who testified at BP’s Deepwater Horizon trial in the US.

Bea also recently warned the low oil price could increase the risk of environmental accidents in offshore drilling by forcing contractors to cut costs, whilst a study commissioned by the US government suggested the harsh conditions in the Arctic would severely restrict the ability to respond to an oil spill in the region.

Clean up matters because, according to the latest environmental impact report, there is at least a 75% chance of at least one large spill releasing over 1,000 barrels of oil over 77 years – the period of oil exploration in the Chukchi Sea.

And the company now acknowledges the risk.

Shell’s own worst case scenario for a spill in the sensitive environment off the coast of Alaska would see 25,000 barrels per day released for 30 days. Just two years earlier the firm believed the worse-case was around 5,500 barrels per day.

So, how would they go about preventing environmental damage from a spill – and does it stand up?

Follow our Arctic oil and gas series

1) Put a lid on it (it may not hold)

Plan A, according to Shell’s most recent plan, is to fill the well with mud, then to employ the blowout preventers to stop a spill.

However the firm’s spill plan accepts that blow-out preventers may fail (as they did in the Deepwater Horizon case) so the company would deploy a capping stack, which is placed on top of the BOP, to try and stopper it. If necessary a containment dome would be dropped over the well to stem the flow of escaping oil.

Finally if all of that doesn’t really work out the firm could try to drill a second well to stem the flow using a second rig.

The problem is blow out preventers fail and when they do stemming a leak can take a long time.

BP had issues deploying containment domes at the Deepwater Horizon spill site. It took took the firm 87 days to put a capping stack in place after the blowout and the spill was finally stopped with a relief well after 152 days.

The Arctic drilling season – the period where the sea is relatively ice free – only lasts 38 days.

Lack of time isn’t the only hitch. A 2014 National Research Council report found “the lack of infrastructure in the Arctic would be a significant liability in the event of a large oil spill.”

It noted: “There is a need to validate current and emerging oil spill response technologies on operational scales under realistic environmental conditions.”

Shell doesn’t yet look like it’s tested its capping stack or containment dome in Arctic waters.

2) Skim it off the surface (there may be ice)

As it scrambles to stem the flow oil Shell’s plan envisages “primary offshore recovery operations”.

That means booms, skimmers and other methods designed to recover the oil before gets near the coastline.

Shell thinks the technology they have will trap 90% of the leaking oil this way, but they accept around 10% may get through.

They hope that half of the remaining 10% of the spill will be mopped up using more mechanical systems skimming the surface of the water.

The problem with their plan is it seems better suited to the climate of the Gulf of Mexico than the Arctic.

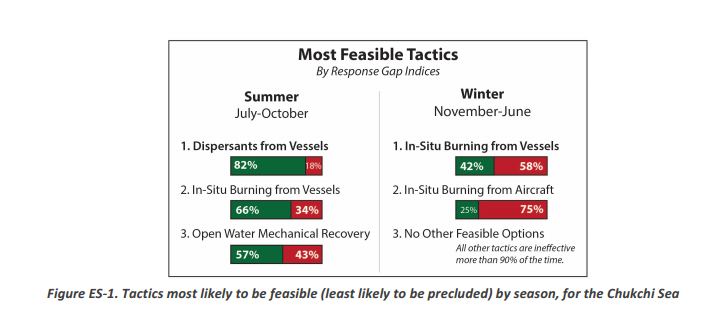

US government commissioned research by Nuka Research and Planning Group into the “oil spill response gap” found that, in their scenario, open water mechanical recovery such as skimming and the use of booms was only feasible about 57% of the time in the Summer drilling window (July to October) because of harsh weather and icy conditions.

“Overall, sea ice has a significant impact on response options, particularly open-water mechanical recovery,” the analysis found. Sea ice, ice flows and ‘skimmers’ don’t go together especially well, in short.

Even in the relatively benign waters of the Gulf of Mexico, a study estimates only 3% of the oil spilled in the Deepwater Horizon disaster was successfully skimmed near shore.

3) Fight ice with fire (you can’t burn under ice)

Shell does outline other ways to deal with the oil — though they are more extreme.

With the weather closing in and the oil still unrecovered, engineers could deploy dispersants or attempt to burn the oil off, both of these may work for a longer period of time in Arctic conditions (see chart below).

But dispersants perform less well in cold and less salty waters, and the toxicity of the chemicals used and oil treated with them could impact the Arctic’s fragile ecosystem.

The US government’s Final Impact Statement for drilling in the Arctic acknowledges this could impact grey whales by killing their food – which could in turn affect subsistence hunters in the region.

In situ burning is a viable recovery option only for two thirds of the summer and less than half the winter. As the weather closes in “the ability to respond degrades very rapidly”, according to Nuka.

4) Just leave it there (they may not know where it is)

By now Shell would be in every kind of trouble their plan simply states a spill would be monitored and the oil tracked so it could be cleaned up the next year.

The National Research Council identified the need for further investment to be able to track the spill under ice and to be able to respond making even this somewhat desperate option hard to implement.