When the levies break: the problem with the UK’s clean energy subsidies

Joss Garman is a Senior Research Fellow on energy and climate change at IPPR @jossgarman

The question of how much funding the government should give to clean energy and home insulation schemes, and where this money will come from, is likely to be one of the trickiest challenges to resolve for the new Energy Secretary Amber Rudd.

The recent nosedive in the wholesale price of oil and gas brought a pause in the increases that billpayers have seen in recent years but the controversy over the cost of energy bills is unlikely to have gone away for good.

During the last parliament MPs voted almost unanimously to financially support clean energy generation paid for through higher levies on energy bills. The chancellor, George Osborne, has stated that by 2020 £7.6 billion will be raised this way and set aside to support low-carbon energy schemes like nuclear power stations, wind farms and carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology.

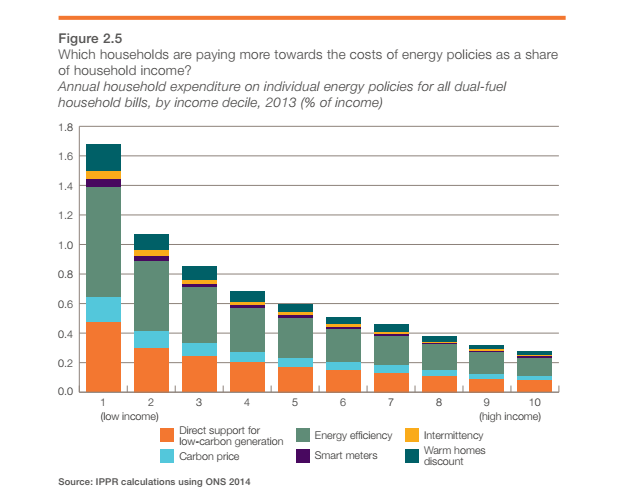

These levies exist alongside other significant charges that government places on energy billpayers – most significantly the carbon floor price, a tax to make dirtier energy sources more expensive, and the energy company obligation (ECO), a scheme to support energy saving.

“Something has gone badly wrong when the poorest households in Britain are paying six times more of their disposable income on government energy policies than the richest households.”

Charges on bills are already projected to more than double through this parliament to 2020. Beyond this point, if the government continues with this approach to financing the low-carbon transition it is expected that some of these levies will have to almost quadruple through to 2030.

This political problem may explain why Ministers have said very little about what they are proposing to do beyond 2020. The Conservative party ruled out adopting a legal target to decarbonise the power sector by 2030, despite pressure from the nuclear and renewables industries and advice from both the cross party House of Commons Energy and Climate Change select committee and their independent advisers on the Committee on Climate Change.

The Prime Minister David Cameron blocked the introduction of a new binding 2030 renewable energy target at the EU level on the grounds that it was ‘inflexible and unnecessary’. Meanwhile, Energy Secretary Amber Rudd has announced that subsidies for onshore wind generation will be ended altogether.

As a consequence of these decisions, there is now a high degree of uncertainty over how much support there is likely to be for any kind of new clean energy generation projects in the UK beyond 2020, and consequently over any energy investments in the next decade.

While opinion polling shows that public support for tackling climate change remains very strong, paying for it through a big hike in green taxes on bills is likely to be contentious. Indeed, the existing contributions extracted through levies on energy bills have already proven to be controversial. That these levies are regressive – being essentially flat consumption taxes which take no account of ability to pay – has prompted consumer groups and critics of action to address climate change to attack ‘green policy’ as something contrary to the interests of working people.

To maintain ambition on cleaning up the energy system, the government should overhaul the funding model for low-carbon technologies to make it fairer.

Ramping up these levies so significantly in coming years would lead to a high risk of a more sustained public backlash, which would be stoked and amplified by influential critics of climate policy in parliament and in the media. This could cause an unraveling of the entire policy framework that underpins the low-carbon transition in this country.

To maintain ambition on cleaning up the energy system, the government should overhaul the funding model for low-carbon technologies to make it fairer. New research from IPPR shows that publicly-owned, privately-run new nuclear power stations could save billpayers up to £5.5 billion. Adopting the development process that Denmark uses for offshore wind could save a further billion pounds. More savings could be made by extending emissions controls on coal-fired power stations, and allowing continued growth in the deployment of the most cost-effective renewable technology, onshore wind.

Something has gone badly wrong when the poorest households in Britain are paying six times more of their disposable income on government energy policies than the richest households.

Without change, the UK’s international leadership on climate change could be unnecessarily put at risk.

Unearthed content does not reflect the views of Greenpeace.