Does the UK coal phaseout spell the end of opencast mining?

Guy Shrubsole is a climate campaigner for Friends of the Earth. Additional reporting by Michael Drax.

The UK government’s announcement last week that it will close all of its coal power plants by 2025 raises further tantalising questions, namely will the UK then also stop digging up coal?

Does it finally mean curtains for the destructive opencast mining industry?

UK mines extracted around 12 million tonnes of coal in 2014, supplying fuel to our 10 remaining coal power stations, plus some ‘metallurgical coal’ for Britain’s remaining steel industry.

Last year we imported some 42 million tonnes of coal from the US, Colombia and Russia. The days when coal mining employed hundreds of thousands of working-class men are long gone.

The UK’s last remaining deep mine, Kellingley in Yorkshire, is closing its doors on December 10th this year. Thirty years ago, at the close of the 1984-5 miners’ strike, coal mining employed around 200,000 men. Now, it employs fewer than 3,000.

The great majority of our domestically produced coal now comes from opencast mining — a process that employs far fewer people than deep mining and causes enormous environmental damage.

Opencasting scars the landscape, pollutes the air with coal dust, disrupts communities with blasting and heavy traffic, and frequently leaves major issues with restoration for years afterwards.

“The local effects of digging up more and more coal are devastating enough – and the global impacts are terrifying”, says Alyson Austin, a resident of Merthyr Tydfil in South Wales, who has lived with opencast mining on her doorstep for years.

Every time I mention to someone that we still do opencast mining in this country, they’re shocked: “I thought that had finished long ago.”

But it’s true: There are some 20-30 opencast mines are currently in operation, planning or restoration around the UK.

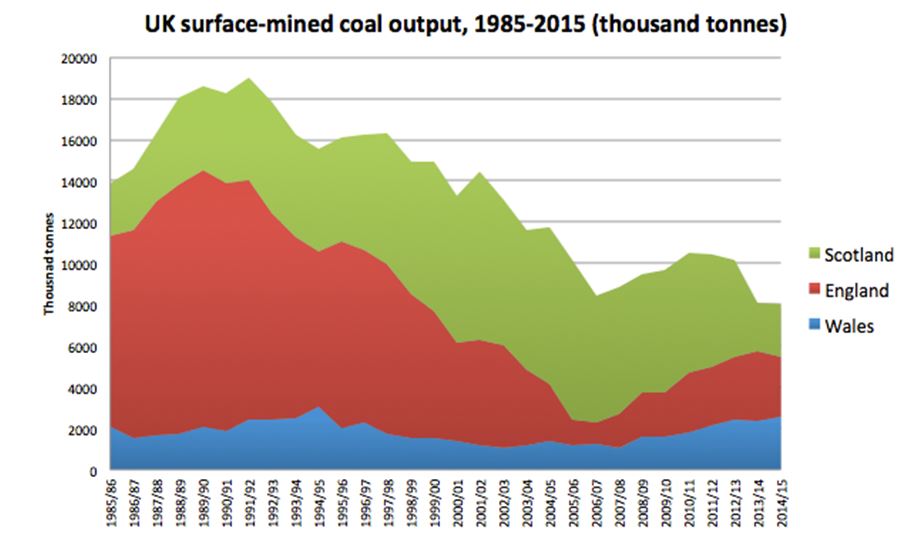

Despite rising concerns about climate change, opencast coal output even saw a resurgence in the mid-2000s which is only now starting to be checked – as the graph below shows.

After Thatcher defeated the miners, the coal mining industry was eventually privatised in 1994, leading to a handful of private companies buying up the mines.

Today, there are five main firms engaged in opencast coal mining in the UK: the wealthy family firm Banks Mining, who run mines on Lord Ridley’s land in Northumberland; Miller Argent, which runs a vast mine in Merthyr, south Wales; Celtic Energy, who own a range of sites across the Welsh valleys; Hargreaves Services Plc, who operate most of the remaining Scottish opencast sites; and the very complex web of successor companies to UK Coal, which restructured in 2012-14.

A handful of other companies operate individual mines.

Friends of the Earth investigations of these companies to date reveal a mixed picture of their financial health and likelihood of surviving a transition away from coal.

The 5 firms have a combined turnover approaching half a billion pounds, with annual profits of over £60m. But whilst some of the companies appear to be in rude health, others – like UK Coal – seem to be in dire financial straits, rocked by low coal prices as well as collapsing demand.

Prior to the government’s coal phaseout announcement, nearly all the firms were boldly asserting to their shareholders that coal still had a secure future into the late 2020s and that fears of an early phaseout were overblown.

It will be interesting to see if any of these firms respond to the government’s consultation next Spring on the details of the coal phaseout, seeking to prolong their unsustainable business models.

Projections from the Coal Authority obtained by Friends of the Earth also suggest the country’s opencast mines will nearly all be exhausted by 2020. So the industry’s output beyond then relies on new opencast mines being approved.

That is by no means a certainty.

Whilst recent years have seen a number of significant mines approved (such as a 500,000-tonne mine at Bradley in County Durham and a 1.2million tonne site at Bryn Defaid in south Wales), there have also been notable rejections of opencast applications.

This summer, for instance, saw the historic rejection of Miller Argent’s proposal for a 6-million tonne mine at Nant Llesg by Caerphilly Council, following years of campaigning.

But it’s not yet game over for the destructive opencast coal industry. Miller Argent may yet appeal Nant Llesg. And now there’s a new front up in Northumberland, where a 3-million tonne opencast mine is being proposed on the beautiful Druridge Bay coast.

Banks Mining, the applicants, operate other opencast mines on land belonging to climate sceptic Peer Lord Ridley. A local campaign group, Save Druridge, is encouraging people to submit objection letters by the 1st December deadline.

German activists have an expression: ‘The end of coal is made by hand.’

As ever, it’s up to the communities.