Comment: 3 reasons why Obama’s coal mine moratorium matters

This is an edited version of a piece published on Medium

Last week the Obama administration announced an immediate moratorium on new federal coal leasing and a comprehensive review of the federal coal program.

It followed the President’s State of the Union commitment to “change the way we manage our oil and coal resources so that they better reflect the costs they impose on taxpayers and our planet”.

There are a few exceptions to the moratorium, such as for metallurgical coal, and mining will continue to happen on federal coal leases — here are the key details of the policy.

Nevertheless, this is a huge deal — because it will keep billions of tonnes of coal in the ground, provide an opportunity to assess the many problems with the federal coal program, and, most importantly, show policymakers may finally be getting serious about limiting fossil fuel extraction.

Let’s break down these reasons why the new coal policy matters:

1. The moratorium will keep billions of tonnes of coal in the ground — at least for now

It has been clear that Interior Secretary Jewell has intended on doing something like this since her speech a year ago in which she called for an “honest and open conversation about modernising the federal coal program”. That was followed by public listening sessions in August 2015 in regions where federal coal is mined.

Multiple government and independent reviews have identified serious problems with the federal coal program, but it did see as though the Obama administration may have chosen to avoid political attacks from the coal industry and their allies.

Fortunately, Secretary Jewell has answered the calls for a moratorium on new coal leasing that have been made since her first day on the job. Some coal lease applications that were far along in the process could still move forward, but many more will not — meaning billions of tonnes of coal will be kept in the ground, at least for the three years that the Interior Department expects the review to last.

2. The review can assess the many ways in which the federal coal programme is broken

The federal coal program has undermined the President’s efforts to address climate change, with 2.2 billion tonnes of publicly owned coal leased for just about $1 a tonne since the beginning of his presidency.

So this moratorium and review is an important chance to better align the management of our publicly owned coal with our national climate policy objectives. But the mismanagement of federal coal has also had serious impacts in many other ways — for taxpayers, communities impacted by coal mining and transport, wildlife, and more.

‘This is an historic action that is much needed and long overdue. It will ensure that the federal government receives a fair return for taxpayers and communities, and balances energy demand with the significant impacts coal creates to our air, land, water, and wildlife resources, and to the global climate, as well as generating important economic activity in our states.

‘We applaud President Obama and Secretary Jewell for taking this action. Given what we know about coal’s costs, and given huge recent changes in the structure of the industry, it’s a critical time for the nation to pause the federal coal program and take fresh stock of the effects this program has on the environment and our communities.’— Bob LeResche, Chair of the Powder River Basin Resource Council in Wyoming

The Secretarial Order emphasizes the breadth of issues that should be considered in the review, through a Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement.

3. It could start the process of putting fossil fuel reserves off limits

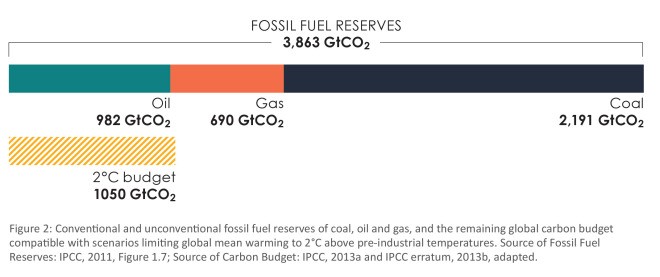

Addressing climate change is of course massively complicated, with overlapping and contrasting ways of approaching problems and solutions. But it’s also possible to look at the essential problem through a simple lens: most of the world’s fossil fuel reserves simply cannot be burned. And that’s particularly true of coal.

But while global climate negotiators and other policymakers have grappled with difficult questions of historical responsibility, equity, transition, and funding when it comes to the global carbon budget, that has been almost entirely focused on carbon emissions — while policymakers have largely ignored the fossil fuel reserves that lead to those emissions. And that has meant that even governments supposedly committed to climate solutions have nevertheless simultaneously promoted increased fossil fuel extraction, as George Monbiot at the Guardian summarized:

‘The absence of official recognition of the role of fossil fuel production in causing climate change — blitheringly obvious as it is — permits governments to pursue directly contradictory policies. While almost all governments claim to support the aim of preventing more than 2C of global warming, they also seek to “maximise economic recovery” of their fossil fuel reserves.’

While climate policymakers have mostly ignored these questions about fossil fuel reserves, scientists have not held back, and an important study published in Nature last year showed that over 90% of US coal reserves must remain in the ground, along with the vast majority of Canadian tar sands, all Arctic oil and gas, and more.

Analysts at Carbon Tracker have also produced detailed reports showing the most expensive and risky coal, oil and gas projects — and therefore which may be most likely to become ‘stranded’ amidst global climate policies and other pressures.

And researchers have confirmed the effectiveness and importance of restricting fossil fuel supplies.

That’s why the moratorium and overhaul of the federal coal program is so important — it signals that the Obama administration is finally beginning to approach fossil fuel extraction as part of its efforts to address climate change.

And critically, Secretary Jewell acknowledged that before this moratorium and overhaul, “our practice was really about getting as much coal as possible”. This is key because it shows an understanding that there really is no neutral approach when it comes to how we manage many billions of tonnes of coal reserves — doing nothing would really mean continuing to promote the subsidised extraction of federal coal.