Comment: China’s distant water fishing industry is out of control

China’s distant water fishing industry is truly enormous.

The country has nearly 2500 boats operating in other countries’ waters or on the high seas — a fleet 10 times the size of America’s.

This number is expected to keep on growing as China continues to pour subsidies into the sector, endangering both the industry itself, and the world’s pressured and over-burdened seas.

Here are five things you need to know about China’s out of control distant water fishing (DWF) industry:

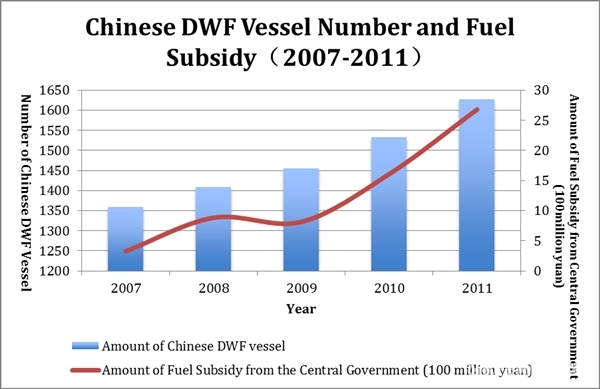

1) Fuel subsidies are increasing

Various forms of subsidies are thrown into the DWF industry, including Beijing’s diesel bonus.

This subsidy protects DWF companies from fluctuating diesel prices by helping to pay off the extra cost of diesel when it rises above 2,870 RMB/tonne, and covers the total extra cost when it rises above 5,070 RMB/tonne.

It increased nearly 10-fold from 281 million RMB in 2006 to 2.68 billion RMB in 2011.

2) Transparency is falling

At the same time, official figures on DWF subsidies have ceased to be released since 2011, making it next to impossible for third parties to analyse the state of the industry and make suggestions to improve its health.

3) Local subsidies are further driving the boom

The number of boats in China’s DWF fleet grew from 1,830 to 2,460 between the years 2012-2014, an increase equivalent to the 16 years of growth between 1994 and 2010.

The boom is highly concentrated in Fujian and Shandong provinces. With generous provincial and municipal subsidies, these two provinces account for two thirds of the growth. Moreover, Fujian has a whopping 400 vessels expansion target by 2020.

4) Overcapacity and unsustainability

An average of 80% of non-operating income for DWF companies is derived from diesel subsidies.

This has put the industry in a situation where it is able to rapidly expand without immediately having to bear the full consequences.

Greenpeace analysis of two large, publicly-listed DWF companies suggests that they would be unable to turn a profit on their operations if it weren’t for the massive fuel subsidy.

However, the consequences are simply waiting to hit.

Much like China’s steel, coal and other industries feeling the impact of the ‘new normal’, the DWF industry is in the midst of a widening over-capacity problem.

For example, between 2012 and 2014 Fujian’s vessel capacity grew by 149%, yet production increased by only 63%. Shandong’s fleet, meanwhile, grew 232%, but production increased only 77%.

If the subsidies were to dry up, the consequences of this unhinged expansion would certainly hit home. It is unsustainable and dangerous to the industry, to the many lives and families supported by it, and to the health of the world’s oceans.

5) In the eye of international dispute

The enormous Chinese DWF is proving a point of contention on the world’s oceans. The sinking of a Chinese fishing vessel by Argentinian coast guard and the detaining of Chinese boats by Indonesia and South Africa, all in the first half of 2016, are points in case.

Subsidies and the growing fleet are creating increased competition for fishing grounds, increasing the likelihood of industry violations and contributing to maritime tension.

The US has already sent a formal request to the World Trade Organisation asking for China to clarify fishery subsidies and bring them in line with WTO stipulations

The issue will come to the fore in just one month as world leaders meet at the Hangzhou G20 to discuss, amongst other environmental initiatives, the phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies, one of which is the diesel subsidy China’s DWF industry is so reliant on.

This is a edited version of an article by Greenpeace East Asia