How a US energy company tried to sell its failing ‘clean coal’ project to the world

The company behind America’s flagship ‘clean coal’ project tried to push the technology on countries around the world, even after they discovered its profound problems, Unearthed can reveal.

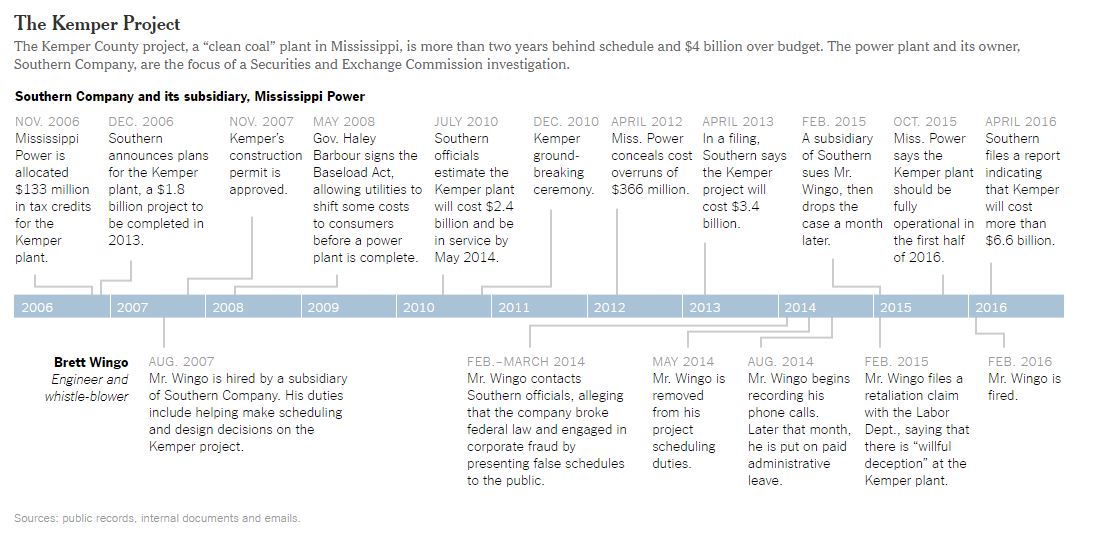

Last month a New York Times investigation chronicled the spiralling costs, missed deadlines, technical issues and administrative chaos at Southern Company’s coal gasification facility in Mississippi.

The Kemper project, as it is called, is currently more than $4 billion over budget and more than two years late, with Southern now promising it will begin delivering ‘clean coal’ power no later than September 30th.

Engineers who have worked on Kemper expect the project’s Kemper’s start-date to be delayed yet again — until 2017.

Dodgy deal

A new look into Southern’s PR operations over the past few years suggests that selling the technology abroad was central to the project’s business model, and the company pursued that in spite of the mounting problems.

In December 2015 the company announced that it had signed a letter of intent with South Korean firm Alps Energy to “evaluate the deployment” of the Kemper technology at one of its power plants.

By this time, Southern was well aware of the crisis unfolding at the plant.

But the South Korea deal has been perhaps the most concrete success of the global ‘clean coal’ offensive, standing out among Southern’s attempts to hawk the technology in Poland, Norway, China, Romania, Serbia and Australia.

Dirty secrets

To understand just how important the international sales element was to Southern, you need look no further than a 2008 memo from Mississippi’s then-Governor Haley Barbour in which he describes the project as a “key piece of America’s and the world’s energy future”.

Less than a year later the company touted a deal with China for its clean coal technology – a proprietary process called TRIG (transport integrated gasification) – even though Kemper hadn’t even broken ground.

Around this time Southern CEO Tom Fanning wrote to the Energy Secretary urging him to divert focus from the bigger FutureGen CCS project in Illinois (the government pulled the plug in 2015) because Kemper was “now ready for commercial deployment” — and that it was being discussed for licensing in China and Australia.

That didn’t end up happening.

Hidden crisis

By 2012, Southern’s subsidiary Mississippi Power had already concealed cost overruns of $366 million, and a year later admitted the project was $1 billion more expensive than anticipated.

In late 2013, an earnings call revealed massive losses and serious delays, with Fanning admitting that they “made a mistake on the engineering”.

The scandal had already cost the jobs of two of Mississippi Power’s top executives, including president Ed Day.

That, however, didn’t stop Southern and the US Department of Energy from taking Norway’s minister of petroleum and energy, along with seven other energy ministers, on a tour of the facility a month later.

Hey Poland

In 2014, months after a whistleblower told Southern officials – including Fanning – that the company had broken the law and misled investors over its false schedule and budget, a top executive flew to Poland for the Wroclaw Global Forum.

There, Karl Moor tried to sell the country on the Kemper technology, claiming the plant was already running and “utilising 65% of the CO2 and sending three and a half million tons of CO2 down a pipeline for enhanced oil recovery” — things that still haven’t actually happened.

“Our first response should be to get Poland the technology so that they can use their native lignite in a strategic way,” Moor said.

“For some reason the Department of Energy for the last 20 years has been helping us develop a technology aimed at Poland’s coal,” he added.

Six months later Fanning and the US Energy Secretary were doing the same thing in Turkey.

Consequences at home

As Southern eyes international deals, the deeply deprived Mississippi county of Kemper wrestles with the plant’s unfulfilled jobs and tax promises.

As Fanning spoke in Philadelphia at the end of July, reaffirming the project’s September 2016 start-date, Kemper residents were called to an emergency meeting on a proposed 41% tax hike to pay the county’s crumbling schools.

The region’s public services have been starved of revenue as long-time homeowners were forced to move in order to make room for the facility’s gigantic footprint.

DeKalb, the town nearest the plant, had to eliminate its police department due to a lack of money.

And, if Southern sells its clean coal technology abroad, the County does not stand to receive any of the proceeds — as per the government agreement.

We got in touch with Southern Company for comment and will update this piece if they get back to us