What causes London’s air pollution?

It’s no secret that London has an air pollution problem – by some measures it’s among the worst in the world, responsible for 9,500 premature deaths every year.

Nor is it a secret that diesel engines are the main culprit.

But on the day that the High Court ruled that the government’s plans to tackle air pollution are illegal, a new analysis revealed a more complex picture.

It doesn’t look good for petrol cars for example, which the data shows produces almost two thirds the amount of nitrogen oxides emissions (NOx) that diesel cars do.

Dirty diesel

As Shirley Rodrigues, deputy mayor for the environment, pointed out at the launch of a new report by think tank IPPR, King’s College London (KCL) and Greenpeace: “If we want to tackle the air pollution problem, we have to tackle dirty diesel.”

Diesel vehicles emit close to 40% of the capital’s emissions of both NOx and the particulate PM10, the report found

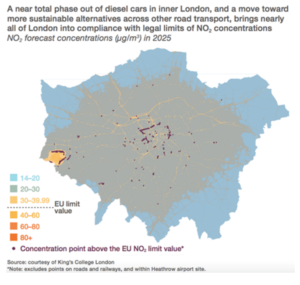

Based on the KCL modelling, diesel cars would need to be almost completely phased out – down to as low as 5% of inner London’s fleet – in order to bring the vast majority of the capital into compliance with legal limits of NO2.

Although even then, some hot spots – on roads in central London and surrounding Heathrow – would still remain.

In order to achieve this ambition and to cut pollution from other diesel vehicles, the left leaning think-tank makes a number of recommendations.

Some have already been proposed by mayor Sadiq Khan – such as the expansion of the ultra low emissions zone (ULEZ) as well as tighter restrictions on HGVs and coaches within it.

Others, such as a diesel scrappage scheme, would require greater ambition, national action or devolved powers. Vehicle Excise Duty (VED) – a tax that currently incentivises the take-up of diesel – is implemented at a national level, so would require devolution in order for it to be reversed.

Of course, policy change on this scale will not be easy – least for the transport industry which may feel threatened.

“We need some genuine carrots….not just sticks painted orange,” said David Leam, head of infrastructure at pro-business group London First.

Petrol is polluting too

Petrol cars are the cause of two thirds of the amount of London NOx emissions (7%) that diesel cars are (11%), according to IPPR’s analysis of 2010 data released by the Greater London Authority.

And when it comes to the particulate PM10, petrol cars are even worse than diesel, causing 16% and 13% of London’s emissions respectively.

Petrol is much less of an issue when it comes to public vehicles, which are largely diesel.

Some of the policy proposals would affect petrol, such as fines on the dirtiest petrol cars in the ULEZ and a boost for cycle and electric vehicle infrastructure.

But it is not a priority.

“If you come from the premise of what is acceptable, we must first reach legal compliance, and then bring levels down to what is negligible. If you have phased out most diesel cars, you can start to look at policies that tackle other sources,” co-author of the report Laurie Laybourn-Langton told Unearthed.

Even so, Laybourn-Langton says it is “inevitable” that London will turn towards petrol before it turns to cleaner alternatives – because of the cost to households and the economy.

“Simply put there are a lot of cars and it will be expensive to switch, particularly for lower income households. At the moment it’s just too expensive for some people to get electric vehicles and there isn’t the infrastructure – the charging points to support them. That’s where central government needs to step up,” he said.

And it’s not just cars

In London, buses are arguably as a big a polluter as diesel cars. TFL buses are responsible for 7% of NOx emissions in greater London and 16% in the centre. And given TFL buses make up the majority of those on London’s streets, the mayor has much more power to accelerate change.

But with almost nine out ten TFL buses currently running on diesel, he has a long way to go.

Of course, buses are a much more efficient way to transport London’s huge population and help keep the number of polluting vehicles on the roads down.

Heavy goods vehicles (HGVs) are responsible for an equivalent amount of pollution to diesel cars (11%) but as Laybourn-Langton points out, “there just aren’t the same technology replacement options with HGVs. The batteries you need to power a vehicle of that size are big and there isn’t the space.”

All of London’s famous black cabs run on diesel. But the capital’s first zero emissions taxi is expected to get its first showing in two years time, at which point no more diesel taxis will be licenced. Khan has also proposed a taxi scrappage scheme to provide grants to incentivise drivers to replace their taxi if it is among the most polluting.

It’s not even just engines

When it comes to particulate pollution, the picture gets much more complex. Only a small fraction of the 29,000 UK deaths linked to particulate pollution are the result of levels breaching legal limits, according to the Royal College of Physicians. The UK is broadly within the law on particulates, but it is far in excess of the levels recommended as safe by the World Health Organisation.

While the report estimates that a diesel phase out would trigger a 45% drop in NOx emissions, PM 10 and PM2.5 would only see a 2% benefit from the policy.

This is partly because the majority of PM10 road transport pollution does not come from exhausts, but from brakes (50%) and tyres (10%). But there are no policies currently in place to restrict pollution from such sources, according to Gary Fuller of King’s College London.

Nor transport

It’s also because the majority (75%) of particulate pollution comes from sources outside of London – from industries such as farming and weather patterns for example – making the issue much more complex to tackle.

When it comes to NOx, road transport is by far the biggest contributor, but there are many other sources, including industry, gas boilers, trains, and many types of machinery from combine harvesters to lawn mowers.

Some of these sources, such as aviation, are intrinsically difficult to tackle because of the chemical process through which the emissions are created.

But others have been neglected, probably due to a lack of scrutiny, research or public debate, which has been dominated by diesel.

Rail is one such example. A 2012 report by Cambridge university found that NOx levels at London Paddington were equal or in excess of those on surrounding roads, largely to the 70% of diesel powered trains that come through the station. But there are no air quality regulations for train stations in the UK.

Even so each of these sources on their own are dwarfed by road transport, which makes up 45% of London’s NOx emissions. So while all sources should be looked at, starting with diesel transport seems to make sense.