Analysis: What does the air pollution plan mean?

After three appearances in court, the government has finally published its long-awaited air pollution plan to tackle illegal nitrogen dioxide levels across the country.

Although to call it a plan might be pushing it a little.

Evidence hidden in the technical report shows that 27 clean air zones are needed – but the government does not mandate any more than the 6 zones in the plan published two years ago. Instead local authorities are told to come up with solutions themselves.

Despite reports earlier this week suggesting otherwise, the government does not commit to a scrappage scheme in the plan. But the consultation moots a scheme for 15,000 vehicles, which includes 6,000 petrol vehicles.

The problem

The government accepts there is a problem.

“The UK currently exceeds the recommended limits for NO2 in 37 of the 43 reporting zones. Road vehicles are responsible for around 80% of NO2 pollution at the roadside so actions to tackle them are central to dealing with the problem,” the report says.

It also accepts that it is a problem that affects the poorest in society most.

“This analysis has shown that a disproportional benefit is likely for those on lower incomes as a result of attempting to reduce high concentrations of NO2. This is due to the fact that lower income groups face higher exposure to NO2 as well as underlying risk factors.”

The solution

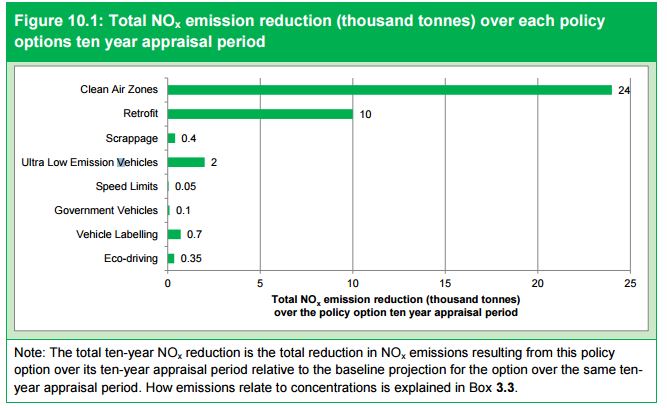

The evidence document lays out 8 options for tackling the issue:

- clean air zones (that either charges dirtier vehicles to enter or encourages the use of clean vehicles in other ways)

- a scrappage scheme that offers consumers financial support to trade in their dirty vehicle for a cleaner one

- retrofitting older vehicles to make them less polluting

- electric and hybrid vehicles

- speed limits

- encouraging government bodies that use vehicles to buy electric or low emission models

- clearly labelling NO2 emissions on vehicles so consumers are more aware

- encouraging people to drive more slowly and carefully

But the government admits that the only effective way to bring toxic air into compliance with the law is to charge polluting vehicles through the introduction of clean air zones.

Their technical report concludes: “All options, except charging CAZs, are shown to be similar to the baseline projection, bringing forward compliance in only a small number of zones where the exceedance is small. It is clear that charging CAZs have the greatest impact by bringing the majority of zones into compliance by 2021.”

Or, in other words, introducing charges on dirty vehicles will bring air pollution down to legal levels within 4 years. Not doing so will only have have a minor impact – in places where there is less of a problem anyway.

Its new modelling (which is not yet completed) shows that 27 zones are needed – including the 6 in the original plan (London, Birmingham, Nottingham, Southampton, Derby and Leeds).

It suggests that clean air zones will be twice as effective as all other options.

“It is clear that charging CAZs have the greatest impact by bringing the majority of zones into compliance by 2021…..By 2021, the Clean Air Zone option is projected to bring more than double the number of non-compliant zones into compliance when compared to other policy options,” the technical report says.

The evidence is clear that the introduction of clear air zones will be the most effective among these, reducing nitrogen dioxide emissions by 24,000 tonnes over a decade, compared to 10,000 for retrofitting and 400 tonnes for scrappage.

Charges

While the plan suggests that charging for vehicles is likely to be the only way it can be legally compliant, introducing 27 clean air zones would not come cheap.

The report states that they would be likely “to have a significant effect on businesses, which may have an impact on economic growth”, but that they would also “deliver benefits to economic growth through improved air quality” – through fewer absences from work, better employee productivity and fewer deaths.

While they will bring £3.6 billion in health benefits, the government estimates that drivers would be charged a total of 1.9 billion, with £600 million price tag for the taxpayer – presumably to set them up.

But when these figures are added together, it shows that clean air zones will have a net positive value of £1.1 billion – making them by far the most cost effective way of tackling the issue. In fact their economic value would be four times greater than the next cheapest option.

Defra analysis shows Clean Air Zones are most cost effective way to tackle air pollution. https://t.co/2n2KMYzjfL pic.twitter.com/vfFRMs9VjW

— Richard Howard (@UKenergywonk) May 5, 2017

Even so, it’s the poorest people who stand to lose the most from charges – but benefit most from tackling the issue.

“Through greater exposure to NO2 and greater prevalence of underlying risk factors, it

is likely that those on lower incomes will benefit disproportionately from attempts to

reduce high concentrations of NO2,” the report says.

“However, specific groups within these populations, such as those who are heavily reliant on the oldest cars or who make frequent use of buses for which they are paying directly, may also be disproportionately affected by the cost of the proposed measures.”

But if the final plan emerges without a scrappage scheme, drivers will have no support to trade in their vehicle for a cleaner one that would not be charged.

And of course, that’s all while car companies are getting away without paying any compensation to consumers for rigging emissions tests in the laboratory.

Local authorities

While showing 27 are needed, the plan itself mandates no additional clean air zones – other than the original six.

Instead, it says that it is the job of local authorities to decide.

“It is for local authorities to develop innovative local plans that will achieve statutory NO2 limit values within the shortest time possible.”

But it makes clear that councils’ plans should only include charging dirty vehicles as a last resort – even though its own evidence shows this to be the most effective option.

“The Government believes that if a local authority can identify measures other than charging zones that are at least as effective at reducing NO2, those measures should be preferred.”

And if they choose to do so, it is their own responsibility.

“Government will only mandate the measures that are identified by local authorities as leading to compliance at the earliest point.”

So, in other words, the government will only take responsibility for measures that councils are prepared to be responsible for.

Discussions are already underway.

What about the money?

There is no additional funding available to councils that has been announced as part of these plans. Councils must apply for current air quality funding – although annual air quality grants did increase six fold last year to £3m. A further £270m for electric vehicles was announced in the March budget, but this includes funding for robotics and articifical intelligence too.

The largest pot cited is the £1.1 billion in the autumn statement is for congestion, public transport and road upgrades – money that seems unlikely to result in less traffic pollution.

Correction: This article was amended on 10 May to amend figures that were incorrect in the original report. The cost to the public of clean air zones was changed from £2.7 billion to £1.9 billion.