Beijing’s air pollution just got worse again

Government targets are at risk following a loosening of controls on industrial output and an increase in coal burning

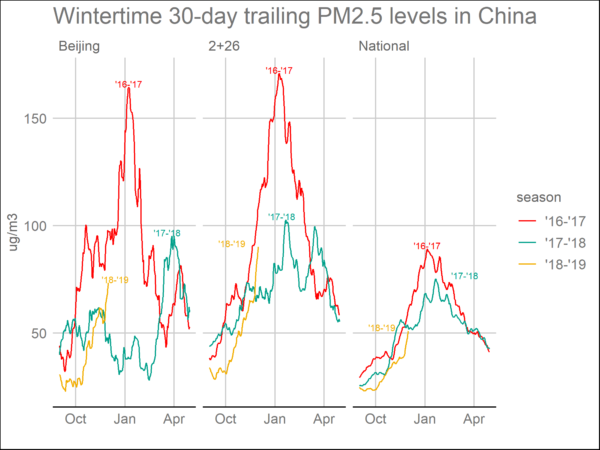

Beijing’s annual winter air pollution looks to be getting even worse this winter, putting government targets at risk, according to a data analysis by Unearthed.

Levels of the particulate PM2.5 in the capital during October and November were 10% worse than over the same period last year, despite a government target to improve levels over the winter period from October to March.

Meanwhile the 28 cities surrounding Beijing, like Tianjin and Zhengzhou, have seen a 4% rise, in contrast to a target to cut levels by 3%.

These early indications that the region’s air is becoming more toxic again following a loosening of controls on industrial output and an increase in coal burning that has also driven a rise in CO2 emissions.

It follows a rising trend in industrial output since summer 2016, prompted by financial stimulus that the government launched in response to a downturn in traditional heavy industry.

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) levels, a pollutant linked with coal burning, have also shot up by 30% in the province.

The war on pollution

The pollution rise comes on the back of several years of progress in Beijing’s war on pollution. Between 2013 and 2017 levels dropped by 40% in Beijing and 30% over the region, following the introduction of new emissions standards for power plants and a period of low coal consumption alongside strengthened enforcement on air quality regulations.

And last year, thousands of industrial plants and millions of households were shifted from coal to gas and electricity, steel and cement output was curbed, and construction projects were stopped in the cities and provinces surrounding Beijing. This had a major impact on air quality around Beijing but only a minor effect on coal consumption, which continued to rise with industrial production.

The anti-pollution drive led to record-breaking drops in pollution, but lead to a winter heating crisis that reportedly affected millions of people in their homes. These measures were very concentrated in the region around Beijing, shielding the area from the impact of rising industrial output nationwide.

The results of last winter’s campaign were also amplified by exceptionally favorable weather – strong winds from the grasslands in the north.

Politics and Olympics

The installation of state-of-the-art scrubbers in power plants have also made a difference, but the industrial and construction surge prompted by the 2016 stimulus has continued longer than expected.

As it looks increasingly unlikely that these polluting economic measures – launched in the run-up to the all-important twice-a-decade party congress where a new leadership is selected – are temporary, expectations are growing in financial markets that another huge stimulus package could be on the way.

This winter local governments were given a lot of leeway to design their own policies for reducing industrial emissions and many appear to have opted for much more lenient curbs than those in place last winter, as evidenced by data from NASA pollution-tracking satellites.

But with China set to host the Winter Olympics in and around Beijing in 2022, pressure is on policymakers to clamp down – or risk either a shutdown of much of the north’s industry or a hazardous smog episode.