Global air pollution map reveals 2,000 cities suffering from dirty air

Big data and consumer monitors join forces to create unprecedented air quality database of more than 3,000 cities

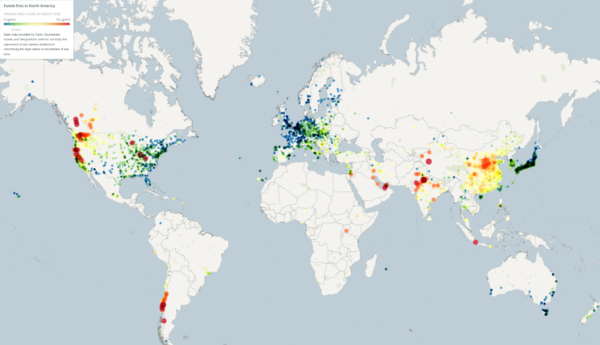

Two thirds of the cities in the world with adequate air quality data are suffering from dangerous levels of pollution, according to a massive new map produced by Greenpeace Southeast Asia and monitoring firm AirVisual.

The map illustrates the scale of the global air pollution crisis, with cities on every major continent suffering from particulate matter levels exceeding recommended limits. Here are some of its more granular findings.

New technology plugging the holes in official data

AirVisual’s global real-time dataset combines information from official government platforms, a total of 86 of them, and uses a worldwide network of consumer-grade air quality monitors to complement the data set where official sources are not available.

Examples of cities where consumer-grade air quality monitors are improving access to air quality data include Lahore, Pakistan and Jakarta, Indonesia, where clean air campaigners have used AirVisual’s monitors to create a citywide air quality monitoring network.

While consumer-grade monitors have a higher range of error than high-grade air monitoring stations costing tens of thousands of dollars, they are making a valuable contribution to plugging the gaps in official data and providing data on a finer scale in areas with official monitors.

If you can’t see the smog it doesn’t mean it isn’t killing you

PM2.5 air pollution is the largest environmental health risk in the world, responsible for millions of premature deaths every year.

PM2.5 means particles smaller than 2.5 micrometres, so small that they can stay airborne for days, travelling hundreds or thousands of kilometres. Their small size means that once inhaled they penetrate deep into the lungs and pass from the lungs further into the bloodstream, affecting blood and internal organs, and increasing the risk of a wide range of diseases.

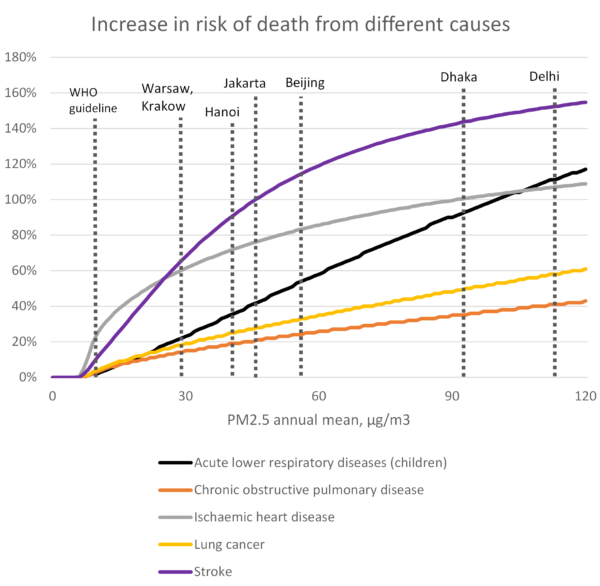

Most PM2.5-related deaths are not from respiratory causes but from cardiovascular diseases such as stroke and heart disease.

The PM2.5 air pollution levels revealed by AirVisual data carry very real and severe health risks. For people living in Jakarta, Hanoi and Beijing, the risk of death from stroke is approximately twice as high as for people living in clean air, and the risk of lung cancer is about 30% higher.

In the world’s most polluted capitals, Delhi and Dhaka, risk of stroke is elevated by about 150%, the risk of death from respiratory infections doubles for children and the risk of lung cancer rises by 50%. These increases in risk are based on the Global Burden of Disease risk model which is developed from dozens of epidemiological studies around the world covering data from millions of people.

The risks are obviously highest at the highest pollution levels, but the increase in risk levels off at extremely high pollution levels, meaning that reducing pollution by a given amount has the largest health benefits for cities that are at the pollution levels commonly found in Southeast Asia and Central and Eastern Europe (15-30ug/m3).

South Asia: 9 cities even more polluted than Delhi

The severity of the air pollution crisis in South Asia is even larger than previously understood, and the new data reveals that no less than 9 cities in South Asia out of the 84 included in the AirVisual dataset have higher PM2.5 levels than India’s famously polluted capital.

Out of 20 most polluted cities in the world, 18 are in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. This includes previously unseen data from Pakistan’s first public monitoring network of sensors. The entire region suffers from bad air, with even the least polluted city in the dataset recording PM2.5 levels three times higher than World Health Organization guidelines.

Jakarta and Hanoi: Southeast Asia’s coal capitals

The two capitals in Southeast Asia surrounded with the largest coal-fired power plant capacity, Jakarta and Hanoi, stand out for their PM2.5 pollution levels, suffering from the highest concentrations recorded in the region.

As official monitoring data is not available, measurements for these cities come from US Embassy monitors and, in Jakarta, consumer grade monitors, many of them installed by Greenpeace Southeast Asia.

Forest fires: North American cities among the world’s most polluted in August

The catastrophic forest fires across western US and Canada last summer had a dramatic impact on air quality, pushing five cities in the region to the list of 10 most polluted in the world for August. None of these cities had air pollution levels anywhere near the global top 100 during the rest of the year.

Enormous gaps in data remain

Almost all of Africa and most of Middle East lack real-time air quality monitoring. South Africa has started deploying a significant number of air quality monitors, but data for calendar year 2018 was not yet sufficient for inclusion to the ranking.

In the most polluted region of the world, South Asia, air quality monitoring situation has been improving but is still lacking far behind China, Europe and North America, with sufficient data available in only 84 cities in a region of nearly two billion people.

Overall, the more than 3000 cities included in the AirVisual dataset only cover 15% of the global population.

PM2.5 is not the only dangerous air pollutant, and many areas that have relatively low PM2.5 levels, such as western Europe and eastern United States, continue to suffer from high levels of nitrogen dioxide and ozone, other pollutants closely related to fossil fuel burning.

Global monitoring coverage for these other pollutants, however, is even worse than it is for PM2.5.

What are the solutions?

The dominant source of PM2.5 pollution globally are fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – along with forest fires and small-scale biomass burning.

Cleaning up our energy supply would therefore see the largest air quality gains, with the protection of forests a close second.

Given the enormous public health costs of air pollution and mounting public concern, there is a need to expand government monitoring networks.

Where official figures aren’t available, new technology enables individual people and non-profits to plug the gaps by installing their own monitors.