A Greenpeace overflight in 2022 documented a large herd of cattle grazing on Fazenda Rio Preto, also known as LH B-90, in Cujubim, Rondônia, a JBS supplier with embargoed land. (Nilo D’Avila/Greenpeace)

JBS admits to buying almost 9,000 cattle from ‘one of Brazil’s biggest deforesters’

Cattle raised on illegally deforested farms in the Amazon belonging to criminal kingpin were sold to JBS slaughterhouses from 2018-2022. At the same time, US and European banks were flooding meatpacker with cash

JBS admits to buying almost 9,000 cattle from ‘one of Brazil’s biggest deforesters’

Cattle raised on illegally deforested farms in the Amazon belonging to criminal kingpin were sold to JBS slaughterhouses from 2018-2022. At the same time, US and European banks were flooding meatpacker with cash

A Greenpeace overflight in 2022 documented a large herd of cattle grazing on Fazenda Rio Preto, also known as LH B-90, in Cujubim, Rondônia, a JBS supplier with embargoed land. (Nilo D’Avila/Greenpeace)

The world’s biggest meat company, JBS, has admitted to buying almost 9,000 cattle from a criminal described by prosecutors as “one of the biggest deforesters in Brazil”, following a joint investigation by Repórter Brasil, Greenpeace Brazil and Unearthed.

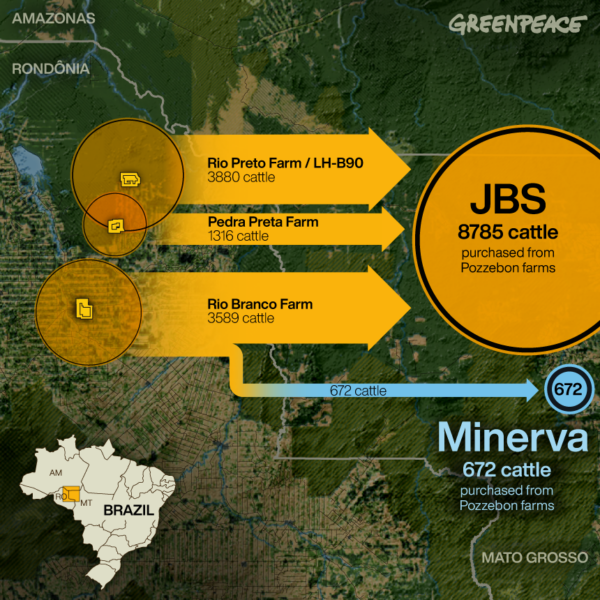

The cattle, which were bought between 2018 and 2022, came from farms in the Amazon owned by criminal rancher Chaules Pozzebon or his family that had been illegally stripped of at least 2,844 hectares of forest cover, the investigation found. Trade records suggest the beef may potentially have been shipped overseas, including to the US.

In a statement to Repórter Brasil and Unearthed, JBS said it was the victim of a cattle laundering fraud and understood that the cows had been reared on a “clean” farm also owned by Pozzebon and his family. Unusually, at a time when environmental enforcement has atrophied and deforestation has often gone unpunished, Pozzebon is currently serving a 99-year sentence for crimes including leading a criminal gang. He has been separately convicted of slave labour. He is appealing both sentences, his lawyer told Unearthed, adding that all Pozzebon’s activities are “lawful and regular, without any fraud or disagreement”.

The Amazon plays a crucial role in regulating the planet’s climate, but is currently experiencing record levels of deforestation. Forest destruction under Bolsonaro hit a 15-year high in 2021, and the forest has lost an area larger than Belgium in the past three years, according to Brazil’s INPE. Scientists warn it has been brought dangerously close to a “tipping point” from which there is no hope of return.

Cattle ranching is the main driver of this relentless destruction: Brazilian NGO Imazon estimates 90% of deforested Amazon land is occupied by cattle pastures.

Major beef companies, including JBS, claim they have rigorous due diligence systems preventing cattle from direct suppliers farms that have illegally cleared rainforest from entering their supply chains. JBS is a signatory to the legally binding Terms of Adjustment of Conduct (TAC) which prohibits sales from properties with illegal deforestation, and uses blockchain to monitor its indirect suppliers. But this investigation reveals that these safeguards failed to prevent large quantities of beef from farms linked to deforestation from entering JBS’s supply chain.

The joint investigation also highlights the links between major international banks and financial institutions and deforestation. At the time when JBS was buying thousands of cattle from a major environmental criminal, it was receiving hundreds of millions of dollars in funding from British, European and American banks and asset managers including Santander, Barclays and BlackRock.

Dirty Business

Born in Brazil’s southern state of Paraná in 1973, Chaules Pozzebon moved to the Amazon state of Rondônia in the late 1990s. He rapidly built a business empire, buying up around 140 plots of land, building sawmills and registering a string of companies in his names and those of family members and associates. As his empire expanded, he collected convictions for keeping workers in slave-like conditions, environmental damage, deforestation, and selling illegal timber.

But it was Pozzebon’s cattle operations that became his biggest earner. According to legal documents seen by the investigation, Pozzebon’s group received R$47m (£8.2m) from JBS between 2015 and 2019 – JBS was often the group’s top source of revenue. In a statement, JBS confirmed that these payments were for cattle. Another major meatpacker, Minerva, was also named in the documents as buying from the group in 2018, with payments totalling R$1.3m (£222,000). Minerva has declined to comment on the allegations directly and told Unearthed it complied with “the highest standards of corporate governance”.

Pozzebon and his mother own three cattle farms in Rondonia which supplied JBS and on which this investigation has identified illegal deforestation: Fazenda Rio Preto, Fazenda Rio Branco and Fazenda Pedra Preta. Cattle transport documents (GTAs) also show that Minerva bought cattle from Fazenda Rio Branco.

Brazil has highly developed systems for monitoring and tackling deforestation – although these were often ignored or starved of resources during the free-for-all of the Bolsonaro presidency.

Under the country’s forest protection rules, the environmental enforcement agency Ibama can impose legal blocks – embargoes – on land that has been illegally cleared. This prevents farmers from using the damaged land, and should block meatpackers from buying any cattle from the land. Ibama records show multiple embargoes and fines for deforested areas in Pozzebon’s name dating from 2006 to April 2022.

One such embargo is on Fazenda Rio Preto, where Ibama has blocked more than 26 sq km for use since 2007.

Repórter Brasil tracked 3,880 head of cattle that were transferred directly from Fazenda Rio Preto for slaughter at JBS units. The cattle were supplied by a company called Agropecuária Rio Preto Eireli, which is registered to Maria Salete Pozzebon, Chaules Pozzebon’s mother.

In 2008, Ibama filed a public civil action against Pozzebon demanding that he restore the area and pay compensation. The court ruled in Ibama’s favour, but 14 years on, Pozzebon has not reforested the area. In fact, satellite images included in the most recent lawsuit show that he has continued to raise cattle on the farm, prompting Ibama to fine Pozzebon a further R$24.6m (£4.1m). Earlier this year Greenpeace Brazil flew over the Rio Preto farm and documented cattle grazing on most of the property.

On Fazenda Rio Branco, a farm registered to Pozzebon’s mother, a 1.65 sq km area was deforested between 2016 and 2018. The investigation team could not find any permits for the clearances. Cattle transfer records show that between 2018 and 2021, JBS bought a total of 3,589 animals directly from Fazenda Rio Branco, again supplied by Agropecuária Rio Preto Eireli.

Cattle transfer documents seen by the team show that another major meatpacker, Minerva, slaughtered 672 cattle from Fazenda Rio Branco. Minerva declined to comment on the case directly and said “We are investigating what occurred based on data publicly and legally available. …Preventively, Minerva Foods blocked all the properties of Agropecuária Rio Preto Eirelli in its system, and also individuals and legal entities related to it making any commercialization impossible.”

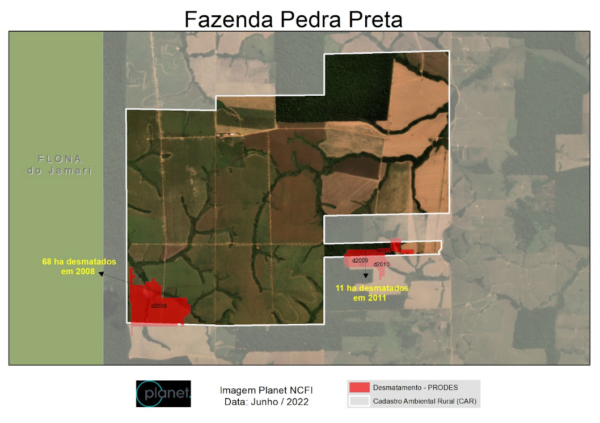

Satellite images show that a third Pozzebon-owned farm, Fazenda Pedra Preta, also saw deforestation between 2008 and 2011. Again, no authorisations were found. JBS slaughtered 1,316 cattle that came directly from Fazenda Pedra Preta between March 2018 and July 2019.

Fazenda Pedra Preta was also the location for one of the most serious charges brought against Pozzebon: his alleged use of slave labour. The Ministry of Labour included the ranch on its 2012 “Dirty List,” after an inspection found 22 workers living in conditions akin to slavery. Three of them were minors.

Inspectors wrote that workers slept on “thin foam on the floor, without any comfort.” They had to wash in streams, and often urinated and defecated in the undergrowth, as there were insufficient bathrooms provided.

Pozzebon was sentenced to nearly seven years in a semi-open prison.

Pozzebon’s lawyer said he was appealing this conviction, and that Pozzebon had no knowledge of or participation in the situation “as it was an outsourced job.”

Despite these charges, Pozzebon had avoided prison – until last year. Between October 2019 and June 2020, Brazil’s federal police dismantled a criminal organisation led by Pozzebon that occupied land, razed forest, and ran 120 logging and ranching businesses across northern Rondônia and southern Amazonas states.

Dubbed “one of the biggest deforesters in Brazil” by state prosecutors, Pozzebon was arrested during “Operation Deforest” and sentenced, in June 2021, to 99 years in prison for leading a criminal gang. Pozzebon is alleged by the federal police to have continued to control his gang’s activities even while in prison – an allegation his lawyer denies.

But even while Pozzebon was under investigation and trial, with the case covered in Brazil’s news outlets, JBS continued buying cattle from farms owned by the gang leader and his immediate family.

When the reporting team presented JBS with the evidence, it confirmed that the purchase records are accurate and admitted to buying cattle from the group since 2015. But the meatpacker says it is a victim of collusion between slaughterhouse employees and Agropecuária Rio Preto Eireli, to register cattle purchases through Fazenda Akira, a farm owned by Chaules Pozzebon that is “clean”, without deforestation or slave labour violations.

“From the information presented by Repórter Brasil, it became clear that the group, in bad faith, had been taking advantage of the leniency of JBS team members to circumvent the system, formalising sales through the Akira farm, but sending cattle produced on farms with social and environmental irregularities,” JBS said in a statement to Unearthed.

“Considering this fraud, JBS blocked Agropecuária Rio Preto, its partners and all persons associated with the group, terminated the team members involved, and will seek compensation in court for the damages suffered, in addition to communicating to other actors in the sector about the activities of this group.”

A lawyer representing Pozzebon denied “any type of fraud or crime in the sales made” to JBS and Minerva. “There is no criminal organisation, but a regularly constituted business group, with lawful activities, authorised by competent bodies”, said lawyer Aury Lopes Jr, in a statement. Lopes Jr – who also represents Maria Salete Pozzebon and the company Agropecuária Rio Preto Eireli – added that there was no criminal deforestation, only “authorised wood management.”

“Chaules categorically denies the media-constructed label, absolutely unfairly and wrongly, of being a deforester or land invader,” Lopes Jr added. “The defence categorically refutes the practice of any crime.”

Lopes Jr added that Pozzebon was appealing his jail sentence.

He added that Agropecuaria Rio Preto, owned by Maria Salete, “does not own farms, it only leases [them] to raise and sell cattle. All commercial operations are regularly declared, with invoices issued, and there is no fraud.”

Breaching Zero-Deforestation Pledges

JBS says it only does business with “cattle suppliers that meet strict socio-environmental criteria”, and does not buy from embargoed farms. But its monitoring systems, developed over the past decade to target deforestation in its suppliers, did not flag any of these sales as problematic despite the connections to a high-profile environmental criminal.

The sales also breach zero-deforestation agreements in the Amazon to which JBS has committed. The legally binding Terms of Adjustment of Conduct (TAC) prohibits sales from properties with illegal deforestation. The G4 Cattle Agreement – signed by the country’s largest beef processors including JBS following Greenpeace International reports into beef-linked deforestation – went even further, blocking sales from properties with any deforestation, including legal.

Audits carried out in 2017, 2018 and 2020 by a private company, as a requirement of the TAC agreement, also failed to pick up on the purchases of dirty cattle.

With the failure of these safeguards, the slaughterhouses that bought the cattle may have been able to export beef that was potentially raised on illegally deforested land overseas.

Trade records from database Panjiva appear to show that from 2018 to 2022, the US reportedly imported thousands of tonnes of beef products from the implicated JBS municipalities, in Porto Velho, São Miguel do Guaporé and Vilhena. US imports of Brazilian beef are growing steeply: from January to August this year, 16% of the beef imported by the US came from Brazil, compared to 6% in the same period last year, USDA figures show.

Bank-Rolling Destruction

Cattle ranching is the main driver of deforestation in the Amazon, and with deforestation soaring under Jair Bolsonaro’s one-term presidency, international pressure has mounted on the meatpackers’ financial backers.

In October, NGOs in Brazil and France wrote to French bank BNP Paribas arguing the bank’s financial support of Marfrig, another of Brazil’s biggest meatpackers, enables deforestation, incursions into Indigenous land, and slave labour. The letter is a required first step for making a formal complaint under France’s 2017 due diligence law.

This type of litigation is likely to increase if laws targeting deforestation tabled in the UK, the US and the EU are passed. In September the European Parliament voted to expand its draft anti-deforestation law to include European financial institutions, requiring their investment portfolios to be screened for links to projects and companies causing forest destruction.

Merel van der Mark, of Forests & Finance, a coalition of NGOs which seeks to improve financial sector transparency and regulation, said that financial institutions had for too long facilitated environmental and social abuses in forest risk commodities.

“Banks that finance JBS and Minerva are complicit in their crimes. They are knowingly pumping money into companies that have a long track record of deforestation, human rights violations, corruption scandals and broken promises. This is not a failure in their due diligence system, but a deliberate choice to prioritise profit over people and planet,” van der Mark said. She added that financial backers could increasingly be exposed to a variety of legal risks.

“With the upcoming due diligence regulations in the EU, banks are facing major legal risk if they continue to finance companies that are involved in deforestation and human rights violations.”

Despite this, repeated reports highlighting JBS’s links to illegal deforestation has not deterred banks and investment funds.

From 2018 – 2022, JBS received a total of $1.1 billion in credit for its Brazilian operations, according to data from the Forests & Finance Coalition of NGOs.

Earlier this month, Bank of Montreal (BMO) provided JBS with a $1.5 billion open line of credit that the company can draw on as and when it needs. BMO did not respond to a request for comment.

JBS is clearly still an attractive prospect for investors, too: financial institutions held $1.2 billion in shareholdings and bond holdings as of October 2022, according to data from Forests and Finance.

JBS’s largest US stakeholders are US asset managers, among them BlackRock, which currently holds $33m in shares and bonds.

In 2020, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink published an open letter pledging Blackrock would “position sustainability at the heart of investment strategy” of the company, the world’s biggest money manager. But in June this year, Fink said that asset managers shouldn’t be held responsible for damage to the planet caused by companies in their portfolios, telling Bloomberg he did not want to be “the environmental police”. BlackRock declined to comment on the record for this article.

The UK is also currently defining a new deforestation due diligence law, although, unlike the EU law, it neither extends to financial institutions nor includes legal deforestation. From 2018 – 2021 JBS received $172m in bond issuance credit from British bank Barclays.

Barclays and Santander were among the six banks to underwrite JBS’s $1 billion Sustainability-Linked Bond (SLB), which was issued in June 2021. SLBs – often known as “green bonds” – allow companies to raise cash to fund sustainable practices, and include targets linked to sustainability as a condition of the funding. But in practice, these targets – and the penalties for missing them – can be feeble.

JBS’s green bond was linked to reducing its scope 1 and 2 emissions: those produced directly from JBS-owned and controlled operations. But the vast majority of JBS’s supply chain – 90% — come from its scope 3 emissions, in its supply chain: the farms that provide it with beef. Even if JBS fails to meet the SLB’s targets, there is no clear penalty.

Banktrack reported that nearly $4.8 billion of orders were placed for the $1 billion issue and JBS itself reported that “the sustainability-linked bond was oversubscribed and resulted in the lowest borrowing cost in the company’s history.”

In July 2021, Santander released a statement, Santander and the Brazilian Amazon, which states it requires “conducting annual reviews of large companies involved in agribusiness” and places a “special focus” on areas that include regions that have seen fires or mass deforestation in recent years, and areas where the expansion of agriculture puts tropical forests or other vulnerable habitats at risk.

Santander told Unearthed that it could not comment on details relating to individual clients but was in “frequent contact with our beef processing clients on this matter.”

“We expect all our beef processing clients to have a fully traceable supply chain that is deforestation free by 2025. If this cannot be established, we will stop providing credit,” it added.

In 2014 Barclays signed up to a “zero net deforestation by 2020” BEI Soft Commodities Compact. But under this agreement, banks pledge to make requirements of their clients with operations in “palm oil, forestry, or soy” – not beef.

In a statement, Barclays said “We apply due diligence to clients with significant beef processing or cattle sourcing operations in South America, including reviewing progress in areas such as traceability of cattle supply chains, and commitments to address deforestation. We consider financing decisions on an entity by entity basis, taking into account our due diligence in relation to that entity and the proposed use of proceeds.”

JBS told Unearthed that it was “opportunistic and inappropriate” to link the “alleged fraudulent and criminal actions of Agropecuária Rio Preto Eireli” to international investors.

“JBS has an open and transparent relationship with its investors who are fully aware of our zero-tolerance policy for illegal deforestation in all Brazilian biomes, or any other illegal activity, associated with our supply chains, and our continuous efforts to strengthen our processes to avoid circumvention by bad-faith actors,” it said it an emailed statement.

“We are permanently in close dialogue with the market to communicate our efforts and share the obstacles that JBS and all companies in the same sector are facing in Brazil. Part of this challenge involves constantly updating and improving our socio-environmental due diligence to stop the attempts of criminal groups to circumvent our control, as was the case in question.”

Minerva is also heavily financed by foreign banks: From 2018-2022 the meatpacker received $853m in credit, including $64m from Spain’s Santander and $60m from the Netherlands’s Rabobank. The UK’s HSBC provided a further $64m.

HSBC’s Agricultural Commodities Policy states that “HSBC will not knowingly provide financial services to high-risk customers involved directly in or sourcing from suppliers involved in deforestation” and that “Global Businesses must investigate incidents of or credible allegations of policy breaches.”

In a statement, HSBC said: “We proactively engage with and help our customers to ensure they operate in accordance with good international practice but end relationships with customers who do not comply with our policies. We are committed to tackling deforestation and will further evolve our policies and practices, in line with emerging best practice guidance.”

Currently, EU financial institutions have $39m invested in Minerva, with the overwhelming majority of this coming from two Dutch pension funds. Minerva’s biggest single investor is ABP, which holds $16m in Minerva shares and is also a major JBS investor, with $31m in shares and bonds. ABP is the national pension fund for employees in the government and education sectors. Its second biggest investor Pensioenfonds Zorg en Welzijn (PFZW), which provides pensions for the care and welfare sector and holds $15m in Minerva bonds.

In ABP’s publicly available Sustainable and Responsible Investment Policy 2020-2025 ABP states that by 2030 it should “be common practice for companies to have efficient and socially responsible natural resource supply chains.” But the statement includes no clear policy relating to deforestation.

ABP told Unearthed that it monitored JBS and Minerva closely and used its influence to hold them to account.

“Periodically, we evaluate whether JBS and Minerva still meet our increasing sustainability requirements, and whether they have taken sufficient steps forward. As soon as these organisations no longer, or too slowly, meet our sustainability requirements, we can decide at any time to no longer invest in the company.”

PFZW said it would look into the allegations made against Minerva and depending on the outcome, this could eventually lead to divestment. However it added:

“We take these allegations very seriously but also believe that by exercising our influence as investor, we can steer a company towards better practices. Therefore we generally prefer to remain invested rather than sell our shares/bonds to others that may not care about these issues.”