Factcheck: Shell commissions Vice style video on how gas can stop climate change – if you are ok with up to 6 degrees warming

Update: Since this article was written Unearthed has done its own analysis on Shell’s energy scenarios and climate change.

Shell is crowd-sourcing promotional films touting natural gas, as the solution to climate change – but Shell’s brief for the film actually describes a world with catastrophic levels of global warming.

The film also shouldn’t mention the firm’s controversial- and high carbon – hunt for oil in the Arctic, according to emailed feedback on one potential entry seen by Unearthed.

The scenario outlined in the video brief (posted online) describes a world that goes well beyond the internationally agreed target of 2 degrees Celsius of warming above pre-industrial levels – the threshold beyond which you can expect mega-droughts, rising sea levels and acidifying oceans.

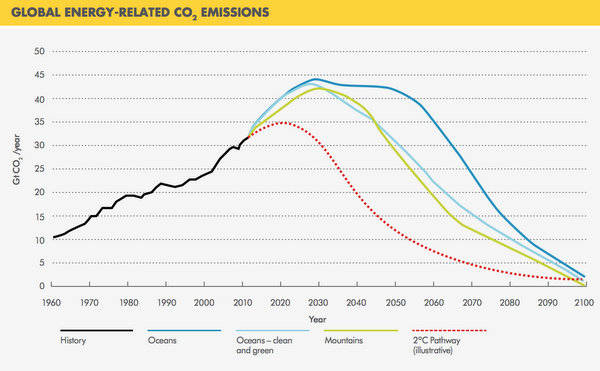

In fact, it reflects Shell’s own energy scenarios, which assumes weak climate policies, and would result in around 6 degrees of warming, according to a Carbon Tracker analysis.

And in an email obtained by Greenpeace a Zooppa staffer acting on behalf of Shell added “you should NOT mention on your storyboard Artic Oil – you can mention instead oil, gas, wind, nuclear energy.”

The energy giant has plans to drill in the Arctic this summer, which has been ruled out on climate grounds by a UCL study.

The brief and feedback suggest the firm is looking to source videos – aimed at young, climate concerned audience – which misleadingly present large-scale fossil fuel extraction, and Shell, as in line with action on climate change and which cover up mention of its oil drilling in places like Nigeria and the Arctic.

‘Dumb ways to die’

“Think of videos like ‘Dumb Ways to Die,” the brief, published on the Zooppa website, urges. Well, indeed – disastrous, preventable climate change does seem like a bit of a stupid way to go.

The video competition is worth $50,000 of prize money, and the brief directs entrants to create a film that “could run on platforms like Vice” and aim their content at millennials (18-34 year olds) who will share the video over social media.

In short, in the run up to key climate talks at Paris at the end of the year, it’s aimed at convincing young people Shell has a solution to climate change – and it’s gas.

The basic scene that Shell describes in its proposal is that energy demand is going to burgeon in the next 45 years, which will mainly be met by fossil fuels. Renewables, meanwhile, are somewhat of a pipe dream.

Here’s a factcheck of the claims in the brief:

1) Global energy demand to shoot up – or not

“The world is going to need a lot more energy than we use now, probably around 80% more by 2050 – with demand for electricity growing even more quickly,” the creative brief states – stating this will happen even if the world acts on climate change.

The problem is, it’s not true.

The claim is almost definitely based on Shell’s least climate friendly energy scenario, called “Oceans”, which describes an 82% rise in energy between 2010 and 2050.

Both of Shell’s “New Lens scenarios” – including “Oceans” and “Mountains” (see graph below) – would add up to a world well overshooting the 2 degrees mark and ending up with something like 6 degrees, according to Carbon Tracker’s analysis.

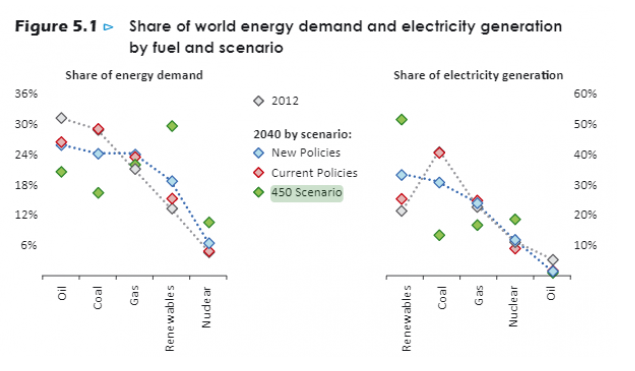

In the IEA’s scenario where we have a 50% chance of keeping global warming within the 2 degrees threshold (450 Scenario), world primary energy demand rises 17% between 2012 and 2040 – so about 63% less than Shell’s gas outlook.

The think tank’s most climate-friendly scenario lowers demand by using more energy savings measures.

In the IEA’s middle “New Policies” scenario – the one that is goes into in a lot of depth because it thinks its realistic we’re going to take some climate action but would lead to 3.6 degrees of warming – it rises by 37% to 2040 (see below graph).

It’s highly doubtful that 37% – or, if we avoid climate related chaos, 17% – in 2040 is going to bump up to 80% in the decade through to Shell’s target date of 2050.

This is mainly because demand for energy is “slowing noticeably over the coming decades… mainly the result of energy efficiency gains and structural changes in the economy, which favour less energy-intensive activities,” explains the IEA in its most recent World Energy Outlook.

2) Fossil fuels “will still provide the majority of the energy we need beyond the middle of this century”

Well, again, it depends if you’re serious about limiting climate change to 2 degrees.

Shell’s energy projections have about two thirds of energy coming from fossil fuels by 2050.

The IEA’s middle scenario (the 3.6 degree one) would also see more than half of energy generation coming from fossil fuels in 2040 – but that involves quite catastrophic levels of global warming.

Meanwhile, the less disastrous 2 degree scenario would see 30% fossil fuels in its mix in 2040 – marginally but finally superseded by 31% of non-hydro renewables – or 51% of the generation mix if you include hydro (see the graph in the above section).

3) Renewables a pipedream? Nope.

Shell – which recently succeeded in lobbying against a binding EU renewables target – writes: “Many people believe that we can do this [tackle climate change] by switching from fossil fuels to zero emission ‘renewable’ energy like wind or solar. This may be true – but it is not going to happen any time soon.”

If we commit to avoiding catastrophic climate change this could come sooner Shell seems to think.

Under every scenario cited by the IEA, renewables (including hydro) look set to make up a quarter of the global energy mix in only five years’ time. And non-hydro renewables will at least double by 2020.

And if we ramp up policies to tackle climate change the IEA’s most recent modelling has renewables down to contribute over half of the energy mix in 2040, becoming the world’s biggest source of energy, driving the majority of emissions reductions.

Some trends indicate we’re already on the path to switching from fossil fuels to renewables – as the impetus to deal with global warming has increased and the costs of renewables have plummeted (especially solar and onshore wind).

Since 2013 the world has invested more in renewables than in fossil fuels, according to a recent Bloomberg New Energy Finance analysis – though it warns investment needs to ramp up to fulfil its potential.

China invested more in renewables than any other country in 2014, while its coal consumption was shown to be in decline that year for the first time.

4) Gas backup a bridging solution

Finally, let’s address the pesky notion of gas backup – widely acknowledged to be needed to plug the gaps when renewable generation is intermittent – but a word Shell also don’t want to use according to the feedback from Zooppa.

Will gas be “the perfect complement to renewables – the flexibility, rapid response times and cost effectiveness of gas power stations make them ideal for this role”?

Here Shell have got something spot on. Gas generation, which can be quickly ramped up and down, is a useful backup to renewables for when the wind doesn’t blow or the sun doesn’t shine – right now.

However, gas generation is set to decline in a world where we limit global warming to 2 degrees. In the medium term gas plants will still exist – it’s just we won’t use very much gas.

The key thing is that gas backup is needed mainly as a bridging fuel until several other solutions come online widely: greater interconnection linking up renewables; battery storage, smart grids, and demand-side management will mean that the demand for gas will be reduced.

Power to gas – for example wind to gas – is also being developed as a way of storing power more seasonally and many solar thermal plants have storage systems. So gas may – or may not – still be needed for backup come 2050, it’s just the gas may not come from fossil fuel reserves.

Millenials manipulation

It’s scary how credible, and well, reasonable, Shell’s Zooppa brief sounds on the surface – the problem is that it’s both dishonest and manipulative.

At best it describes a world where carbon capture and storage will be deployed onto gas plants the world over to capture carbon dioxide from fossil fuel use whilst energy use rises exponentially.

Yet Shell know that no scenario exists that suggests CCS can mitigate the kind of gas use Shell imagines without catastrophic climate change. Even their own modelling suggests that by 2050 less than a third of CO2 will be captured – and Shell has been criticised for doing little to push this forward.

Of course, it could be that Shell are right and the likes of the UN’s climate scientists and the IEA are wrong – maybe we can burn lots of gas and avoid the worst effects of climate change. Or maybe they just wanted to do a little Arctic-oil free greenwash aimed at an audience they regard as young and impressionable.