Nationalise, decentralise & decarbonise: What might Labour’s new energy policy actually look like?

Imagining Labour’s energy policy over the next five years is – to put it bluntly – a little confusing.

The new leader, veteran left-winger Jeremy Corbyn, is best known for claims he wants to nationalise things – and he does – yet when you read his “environmental manifesto” the word ‘nationalise’ doesn’t appear.

Instead it’s all about devolving power (in all senses of the word) to communities, businesses and local government.

Indeed speaking to me about his ambition for tens of thousands of rooftop solar panels, Corbyn said “it is simply not credible or possible to make that into a mass public corporation.”

In short the manifesto is about the sort of things you’d expect his new Energy Secretary Lisa Nandy – and many other parts of the party – to be keen on.

Writing in the Guardian, alongside Corbyn’s leadership rival Liz Kendall, Nandy claimed that the “new Labour politics of the state is about putting power in the hands of people”.

“We must champion the power of human beings to shape their own lives, and oppose the tyranny of the bureaucratic state,” added the new Shadow Energy Secretary whose background is more in tackling poverty than climate change.

Yet alongside the emphasis on social justice there is a strong ‘green’ component to Corbyn’s support base – which attracted the support of Green MP Caroline Lucas – even if his actual policies sometimes fail to live up to the billing.

Green tension

How the tension between the green and red strands and the centralising and decentralising tendencies plays out will be crucial to defining not just Corbyn’s own agenda but possibly an entirely new energy and climate consensus.

It could be a total mess, simply a proposal to add to the existing quagmire by spending billions on nationalising old coal plants nobody wants or needs anymore. But there is a chance for something new.

It starts where the consensus currently is. That to have a chance of playing its part in avoiding the worst impacts of climate change, the UK needs to generate almost all of its power cleanly within 15 years.

To do that, the country probably needs to cut down on fossil fuel exploration in its own backyard – fracking, for example, makes little sense unless the Gulf states can be convinced to cut down on their own gas production. Asking them to do so, whilst refusing to do so ourselves is intellectually legitimate – but may make for a poor negotiating position.

And so things start to diverge from where we our now.

The current direction of policy (in as much as there is one) is basically about very big stuff being built by very big companies backed by big money on big returns with big(ish) bills for consumers.

The power produced by existing coal, gas and nuclear plants are to be replaced with a new fleet of nuclear power stations, coal – with the carbon dioxide captured and buried – and huge arrays of offshore wind turbines.

Decentralised generation

Smaller scale renewables – such as onshore wind and solar – will play a role, but far less of one than in other advanced European economies.

But that order could be reversed.

Smaller scale renewables,owned by communities, households or even local governments (what Corbyn quaintly calls ‘municipal ownership’), would be the focus.

That wouldn’t just mean direct support for tens – maybe hundreds – of thousands of homeowners, farms and businesses to put solar panels on every bit of roof they own.

It’s also about larger projects backed by communities, co-operatives, local councils or small businesses.

Back to the Victorian model?

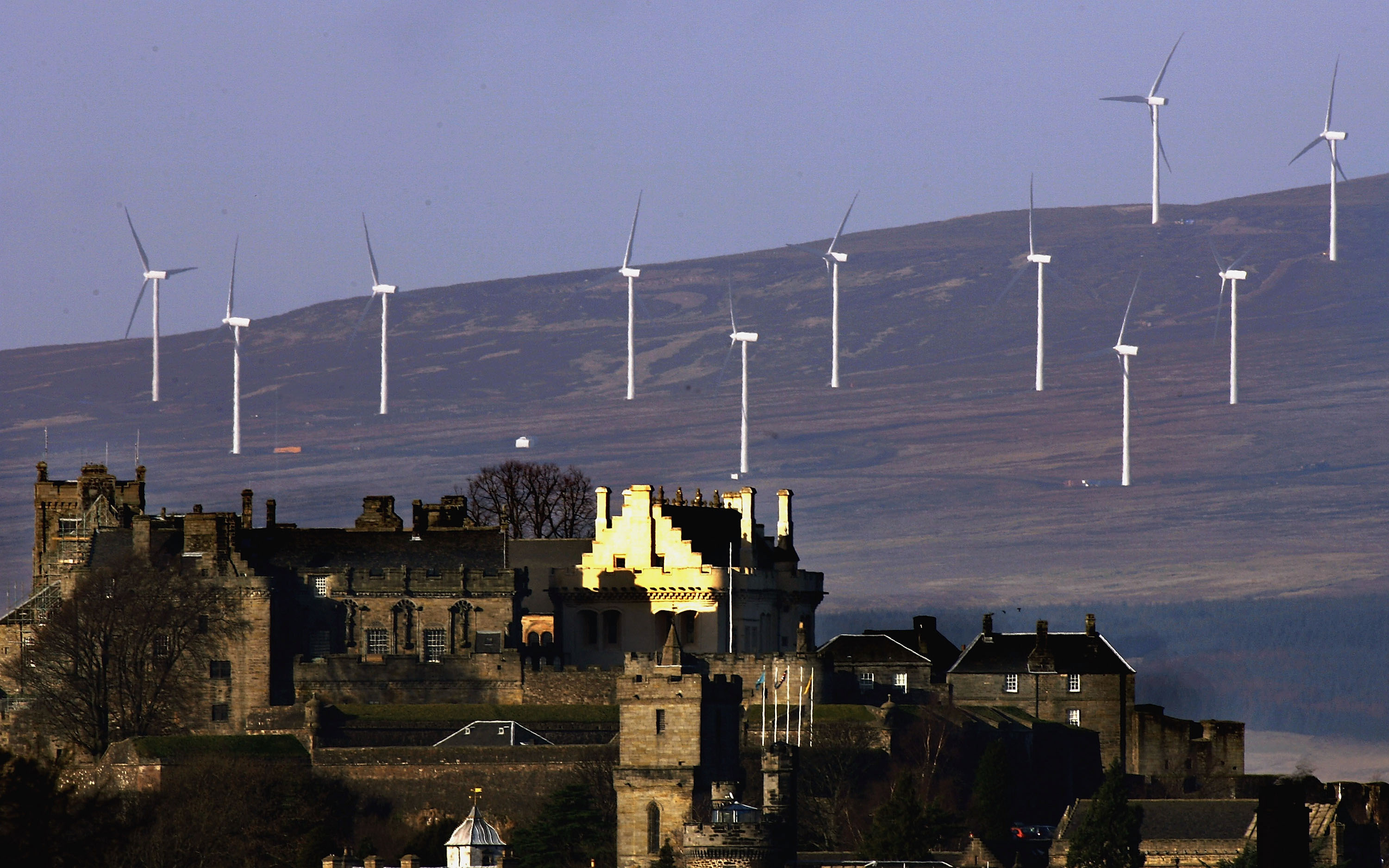

Think wind farms in Somerset owned by the local council – or Bristol city. It’s a vision which harks back to the days before nationalisation, to the way things were back in the Victorian era.

But empowering households and cities only takes you so far. The legacy of the Victorians – and industrialisation – is that there will always be arguments over what proportion of the UK’s countryside can be given over to energy generation.

This is not a concern on which the right has a monopoly.

Too many solar farms

Even Corbyn says he finds it sad “when I see farmland taken over to be given into solar generation thus using crop space or grazing space.” You still need some big stuff producing energy more efficiently over a smaller area – or just far out to sea.

That means large offshore wind farms, giant tidal projects, nuclear or coal plants with facilities to try and capture the carbon dioxide they create.

In the current set-up though these are built, owned and operated by the utilities – the same firms Corbyn has threatened to nationalise.

But whilst that may have been the solution for the left in post-Victorian times – when the power stations had recently been built – it would be a curious option now. Why would the government want to buy a bunch of ageing coal and nuclear plants it is looking to close? Even the energy companies themselves don’t really want to own them.

The more realistic option is common ownership – but from the bottom up.

Common ownership from the bottom up

A German-style Investment Bank – which Labour now supports – would be able to borrow money at treasury rates to provide matching loans for projects large and small. From a solar panel on a farm shed to a new offshore wind farm this would dramatically lower the cost of new power generation.

The downside is that the risk – of the power plant not working – is socialised, but isn’t it already? If a new power plant doesn’t work the company that built it can’t be allowed to simply go under or the lights will go out.

Indeed under the current model the government is proposing to guarantee billions in loans from the Chinese state to the French state owned EDF to build Hinkley point C . Yet the loans will still attract private-sector rates of return.

In short risk is socialised in every conceivable sense whilst profits are privatised and offshored – a curious idea on which to build a consensus.

But all the money can’t come from the magic bank with the treasury loans – not least because national banks, like governments, when acting alone, have a history of poor investment decisions.

Instead investment from the big utilities and foreign governments would be replaced in part by crowdfunding on a national scale.

National crowdfunding

Green ISA’s – a Conservative idea – could allow investment funds to raise money directly from consumers to invest in new clean energy projects which benefit from fixed rates of return.

More Corbynite perhaps would be building on models established in Denmark and Germany to allow individuals and businesses to own stakes not just in ‘small scale’ community projects close to their homes but also large-scale projects, such as offshore wind – indeed sometimes this is a condition of the project going ahead at all.

Finally the government could build on existing policy to encourage switching providers by making it both easy and beneficial for consumers, businesses, institutions and local authorities to opt to source their power from clean sources through simple online switching systems, by building in tax incentives for clean energy providers and by creating the legal structures necessary for the owners of clean energy projects to sell their power directly.

Rather than nationalising the Big Six these policies would effectively bypass them. No longer holding a monopoly on power generation there would be increasingly little reason for anyone to buy their power from them.

Fewer subsidies

At the same time the current system of complex government set subsidies to major power producers would also be challenged by towns, co-operatives and new energy companies now able to buy power directly from each other.

And this is probably where the nationalisation comes in.

Bringing in a new, distributed and clean energy system from the bottom up sounds great – but it could lead to chaos.

What happens when the wind doesn’t blow, the sun doesn’t shine and that new coal plant with carbon capture turns out not work?

Central planning is deeply unfashionable, but markets & competition are good for driving efficiency and setting prices. Less so for achieving purely ‘social’ goals – like keeping lights on.

Nationalise the grid

The National Grid’s role would be crucial – helping to decide how much solar, for example, can be integrated, what level of interconnection is needed with other countries, how & where energy can be stored. Energy systems do not devise themselves.

Yet right now the grid – which is effectively an arm of government policy – is a regulated, private, monopoly.

As with the railways Corbyn wants to nationalise it, giving it access to cheap capital to build infrastructure and the government the power to influence what it charges to who.

Whether that is a good idea depends how effective one thinks governments are versus private monopolies. It’s not a great choice but to be clear nobody wants rival national grids building competing pylons across the the country. I think.

But even here, nationalisation only takes you so far.

He may be in Labour’s sights but the chief executive of the National Grid agrees with the Labour leader that the era of large ‘baseload’ power stations is over.

Smart fridges, electric cars

What is needed instead – he argues – is new technology which helps balance supply and demand alongside electricity storage. Think fridges which turn down when power demand is high, Tesla battery walls and tariffs which encourage you to charge you car when power is cheap.

To deliver that, a nationalised grid – or state regulator – would need to enforce standards, such as ensuring all household devices can respond to demand, and create incentives for businesses or consumers to become more responsive. There isn’t much of this in Labour’s current plans – but it’d need to be there.

All of which brings us to the issue of bills and the tension between a policy designed to promote investment (drive up bills) and deliver better living standards and social justice (drive down bills) at the same time.

Many of the policies designed to deliver clean energy without the Big Six are also designed to lower costs – by cutting out high borrowing costs or private sector rents and encouraging user owned models. But re-building an energy system still costs money.

Cut bills, cut energy use

The problem is not just that building clean energy needs lots of capital up front, but also that bills are – essentially – a flat tax, which hit the poorest hardest.

The perenial, yet abysmally implemented, solution is to encourage efficiency and – most likely – to promote renewable heating in people’s homes so as to reduce their need for gas.

The problem is that spending on these measures is – itself – funded through bills meaning that the poorest households must pay significantly more for schemes which, even if they get them, will only save them significant sums of money over a decade or so. Efforts to loan people money at commercial rates to install their own measures proved so ineffective they’ve been abandoned entirely.

It is a failure which could fairly easily be solved by treating heating and efficiency the way the state treats other health and productivity issues – with the cost socialised and spread over the lifetime of the investment. After all, sickness caused by fuel poverty costs the NHS millions.

In simple terms that means using an Investment Bank to fund new measures at ultra-low rates of interest – both to companies which install efficiency measures and to households themselves – and using taxation to offer support for those households in fuel poverty.

Switching the responsibility for installing these measures away from the big energy companies who sell the gas and towards local co-operatives and councils could be more likely to deliver results.

At this stage this is all somewhat hypothetical. We don’t yet know how the tension within Labour’s energy policy will play out. But one thing is clear: a future Labour agenda may turn out to be far less about nationalising the big players and more about bypassing them entirely.