Factcheck: Is fracking compatible with action on climate change?

One of the arguments around shale gas extraction in the UK has been about whether or not it is compatible with the UK’s aim of preventing catastrophic climate change by limiting emissions from fossil fuels.

It’s not as obvious as it may – at first – appear. The person in charge of the UK’s climate and energy policy, Amber Rudd, has said fracking gas is a low carbon source of power – comments that were recently repeated by Labour peer and anti-coal campaigner Bryony Worthington.

The suggestion is that because gas is lower carbon than coal it can play a role in tackling climate change.The problem is that shale gas is obviously not lower carbon compared to renewable technologies such as wind and solar or nuclear. And saying fracked gas is low carbon implies it’s a low climate risk, which simply isn’t the case, for several reasons:

1) Coal to fracked gas switching in the UK won’t happen

Sigh. The argument that gas from fracking can replace our old coal plants in the UK is one we’ve debunked before.

Assuming that we do take action on climate change to stay within the internationally-agreed 2 degrees threshold – and dodge more severe droughts, floods and storms – fracking will come too late to the party in the UK.

To stay within ‘safe’ levels the government’s climate advisers, the Climate Change Committee say we really need phase out coal sharpish – by the early 2020s.

Fracking, however, won’t be online in commercially significant amounts for another 10-15 years – if it goes ahead. This timing means fracking won’t be able to push coal off the system, something a 2015 Environmental Audit Committee report on fracking pointed out in its conclusions.

Even if fracking gas came online sooner, it would likely be in proportionally small amounts and be more expensive than coal – so it wouldn’t displace it.

2) Coal to fracked gas switching won’t happen in Europe

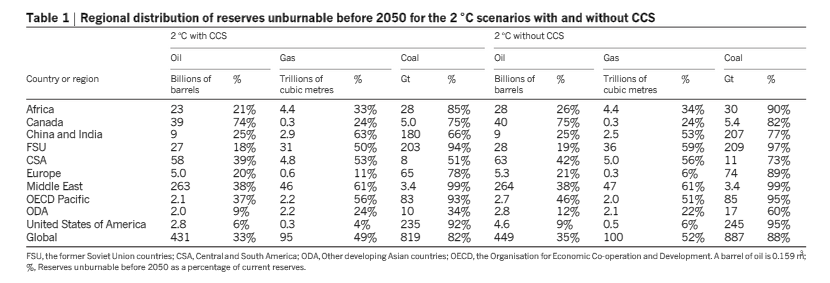

If you take a wider perspective, fracked gas still won’t replace coal. A seminal modeling study published in Nature at the start of the year found that we have to keep 78% of known coal reserves in the ground in Europe by 2050 to stay within two degrees – and that’s with CCS. Without it that figure rises to 89%.

Whereas we can probably still burn most of our gas reserves in Europe and stay within 2 degrees.

The problem lies in the fact that – as one of the report’s authors environmental policy professor and director of UCL’s Institute for Sustainable Resources Paul Ekins puts it: “If there were to be considerable unconventional gas extraction in Europe it would need to substitute for other reserves that are burned in our current scenario”.

This is because the gas burned in the UCL study scenario does not include European shale gas reserves. This makes sense, because you would expect the cheapest gas to be used first – and fracked gas is more expensive than conventional gas, according to the IEA and Ernst and Young.

3) Fracked gas won’t replace coal globally, or Qatari LNG imports

A 2013 government report known as the MacKay report, led by Professor David MacKay, concluded that: “In the absence of global climate policies, we believe it is credible that shale-gas use would increase both short-term and long-term emissions rates.”

This is because “The production of shale gas could increase global cumulative GHG emissions if the fossil fuels displaced by shale gas are used elsewhere”, in the absence of such an agreement.

As MacKay points out, this shunting of emissions from one place to another is already going on in the US, where the shale gas boom has had a role in reducing domestic demand for coal – but increasing coal exports to other regions.

In fact, we don’t just need a global climate agreement- which will be discussed at the Paris climate talks in December and could pave the way for a 2 degrees world – for fracked gas to replace coal globally you would also need whole new international mechanisms.

“You can only use lots of gas while staying within the 2oC limit if it implicitly and explicitly substitutes for coal, and at the moment there are no institutional means to ensure that,” Ekins told Unearthed, “any case for sustainably burning new sources of gas needs to say what fossil fuels it will displace, and be clear about compensation arrangements that would need to be put in place if cheaper fossil fuel reserves are to be displaced in other parts of the world.”

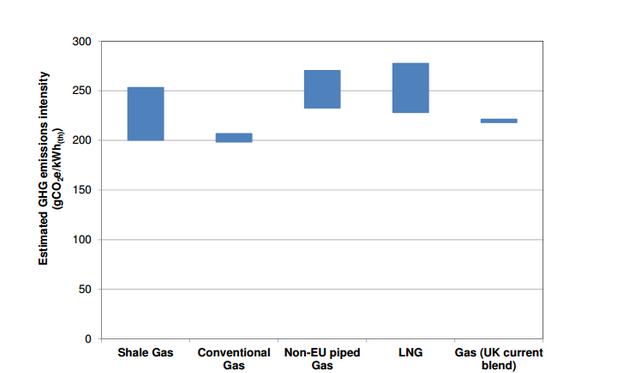

Similar arguments could be made for shale gas displacing LNG imports from Qatar as displacing coal. LNG from Qatar has a higher carbon intensity than fracked gas is estimated to have according to the chart from MacKay, below.

But this assumes that 90% of methane released during the process are captured and flared. This 10% that’s emitted could be more or less important – evidence is mixed. Studies looking at the methane emissions from fracking in the US vary from saying that they are lower than previously thought to saying they have been grossly underestimated.

Anyway, if there’s no global agreement or mechanism to substitute energy sources, then Qatari LNG will just get burnt elsewhere.

In theory, a global carbon trading system could be a step towards internationally traded emissions allowances – but it’s unfeasible and the EU emissions trading system has so far failed to work.

4) If we frack, we could undermine UK climate leadership

John Ashton was the government’s special envoy for climate change for six years until 2012, and says climate diplomacy – the very thing that could resolve the issues about displaced emissions – is a good reason not to frack.

In a speech last year he said it would become impossible to ask other countries to leave their conventional reserves in the ground while going “hell for leather to extract unconventional gas and oil from under our own feet.

“We would no longer be listened to,” he added.

5) Fracking could detract from investment in renewables

Ashton – who has said people who think we can deal with climate change and frack “are being ignorant, or deceitful, or deceiving themselves”- also argues that even if fracking displaced a little conventional gas in the UK, exploiting unconventional resources would lock us into a dependency on gas – and therefore create a chilling effect on renewables and energy savings investment.

Indeed the evidence from the US shows not only that the shale gas boom was not a major factor in reducing US emissions – as previously thought – but that part of the problem was that shale gas didn’t just substitute for coal but also for clean energy.

Ashton’s words echo warnings by professors from Harvard and MIT, and UK’s The Tyndall Centre. MIT Professor Henry Jacoby, an expert in environmental policy, said: “there had better be something at the other end of the [gas] bridge”. Given the current state of UK policy on renewables it’s hard to work out what that might be.

6) And no, Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) isn’t a get out of jail free card

Some have argued that all these problems can be overcome if shale gas is only used in circumstances where the carbon emitted is captured and stored someplace underground, for ever.

To start with this suggestion is highly impractical. Much of the gas we use is for domestic heating where this technology can’t work.

Of course gas is also used for power generation. But taking shale gas, which is already expensive, and using it to fuel a technology which has been a long time coming and is currently only economically viable if you use it to stimulate oil extraction seems – at best – an odd approach to tackling climate change.

Still if you did want to do this it would be better – from a climate point of view – to burn gas from existing reserves rather than increasing global supply still further while arguing for fossil fuels to be kept in the ground.