All is not well with nuclear in China

Not even China likes the reactor its state-owned nuclear power company is helping to build in the UK.

With its reactors at Taishan, models for the proposed Hinkley project, beset by lengthy delays and spiralling costs, Beijing appears to have soured on the European Pressurised Reactor (EPR) technology.

According to the World Nuclear Association, beyond the two at Taishan it has already committed to building and potentially a further two in planning, the only EPR reactors China will be associated with will be overseas.

“Overseas projects involving CGN appear now to hold the only potential for expanding the role of Areva’s EPR technology involving China.” — World Nuclear Association

Four may sound like a perfectly respectable number, but in the scheme of China’s grand nuclear plans, it’s next to nothing.

China expects to build around 40 nuclear power plants over the next five years, with Beijing preferring the other third-generation reactors, including the AP1000 due to be built in Cumbria and especially the Hualong-One to be built at Bradwell.

The nuclear industry does not agree with our reading of the prospects of the EPR in China.

Industry rep David Hess told Unearthed that although there are no current orders for further EPRs in China, this “does not appear to be because of any issues experienced with the design” — rather that the government is focused on supporting its domestically designed Hualong-One reactor and other technologies such as SMRs.

It’s not as though things are going smoothly for China’s other imported 3rd gen reactor.

AP1000

“The AP1000 units at Sanmen [in Zhejiang province] were due back in 2013 and 2014,” Antony Froggatt, energy research fellow at Chatham House, told Unearthed.

“They’re now talking about finishing both of them sometime this year — so far they’re 18 months to two years behind schedule.”

The reactor, designed by US energy company Westinghouse, which is now owned by Toshiba, may be considered the superior imported third-gen reactor but – like the EPR – it’s riddled with problems.

According to M.V Ramana, a nuclear physicist at Princeton: “The main problem with the AP1000 has been with the reactor coolant pumps (RCPs), which are manufactured by a US Company called Curtiss‐Wright.”

He told Unearthed: “They messed up and shipped what amounted to defective RCPs to China for the sites at Sanmen and Haiyang, where these failed in the tests that the Chinese ran on them.”

The RCP issue was resolved towards the end of last year, but it’s symptomatic of a wider problem with these new nuclear projects: It’s hard to get factory-produced modules right.

It doesn’t end there though.

The company, which Chinese nuclear expert Li Yulun has accused of failing to take safety seriously, has also struggled to navigate the US government’s rules for exporting nuclear technology.

And even at stateside nuclear power stations, reactors have been hit with costly delays that have raised doubts over the much anticipated new nuclear revolution.

CGN

If China thinks the troubled AP1000 reactor is a better bet at home than the EDF/Areva EPR, you’d better believe there’s a lot wrong with the latter.

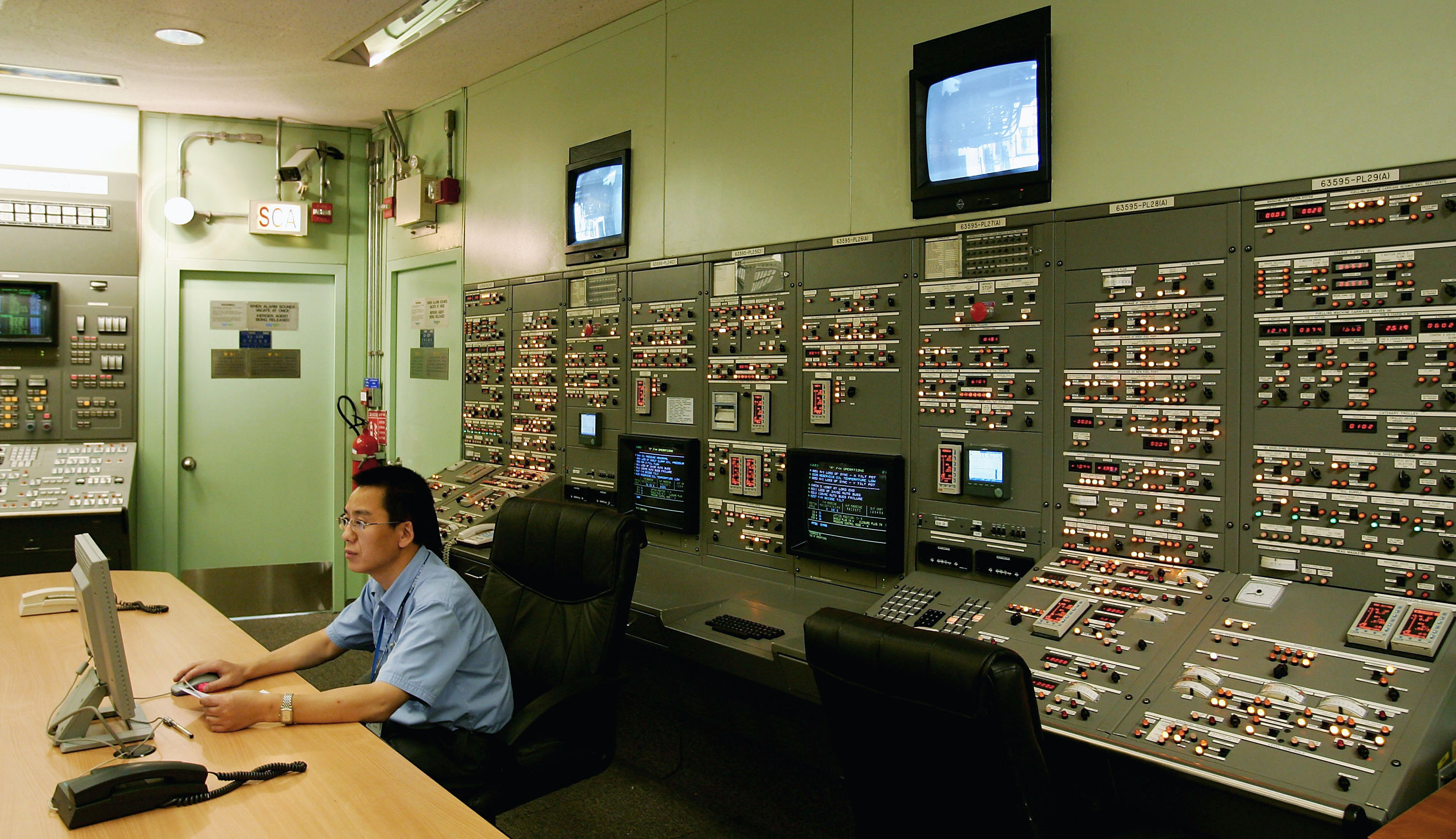

Built by the China General Nuclear Power Company (CGN), which is notorious for delivering projects late, not only are the Taishan reactors years behind schedule, they’re billions of pounds over budget.

CGN claims it has spent 20% more than it expected to — but nobody trusts that stat.

Since June of last year, the company, which was floated on the Hong Kong stock exchange in late 2014, has seen its share price tank — it’s now worth less than half what it was.

(It is worth noting, however, that Chinese companies across the board have battered by the stock market over the past year)

At this point CGN is refusing to continue construction on key parts of the EPR until the French can assure them that technical specifications are up-to-standard.

Just the other week a state official bemoaned yet another safety setback, saying they are “waiting for the results from the French side” and “won’t resume construction on the [pressure vessel] until they can remove all safety concerns”.

To its credit, China has taken a number of safety steps since the Fukushima disaster of 2011.

In any case, CGN remains set to be the global face for China’s civil nuclear sector.

Ramana said: “The way I see it, CGN’s main challenges in entering the global reactor marketplace are the widespread perception that Chinese designed reactors are lacking in safety.

“They are trying to ease concerns over Chinese companies lack of experience outside the country, with the design and construction of the Hualong-One reactor seen as one way to remedy that.”

In his analysis in the World Nuclear Report, Professor Stephen Thomas from Greenwich University said the delays of the two reactors are “similar to each other” and “comparably bad”.

“Both designs have suffered a serious design issue that has delayed construction,” he wrote rather straightforwardly.

Missed targets

Despite the struggles at Senman and the travails and Taishan, these two reactors are getting built — the government will make sure of that.

But this experience may impact the way in which China approaches its ambitious nuclear plans.

Referring to the country’s recent financial foibles, Froggatt explained: “The current situation in China is more likely to affect the future reactor plans than to impact the construction of these two projects.

“If they’re supposed to be completed in the next year then most of the construction investment would have occurred.”

Of China’s plans, he said: “There’s no getting around it. What China is proposing is huge in global terms. Already around 40% of the world’s nuclear reactors are being built in China.

“Will they achieve their ambitions? There are certainly barriers to doing so. Some concerns around overstretch have been raised. Are they doing too much?”

Particularly if they want this fleet of new nuclear plants to be of the later generation variety, which Froggatt said would “not only have cost implications, but would also take longer to build — meaning it’s harder to meet such ambitious objectives.”

He points out that China has very specific five-year plans and clear long term goals, but – so far – with nuclear “they haven’t achieved their targets”.

“The target for 2015 wasn’t achieved. But they’re confident they’ll meet the 2020 one.”

Article was updated on Feb 22 to include comment from nuclear industry rep David Hess