Documents reveal Shell’s demands for relinquishing oil rights to fragile region

Shell have attempted to use old – and possibly even expired – oil exploration permits off the northeast tip of Canada as a bargaining chip with a marine protection committee trying to increase protection for the ecologically fragile and culturally sensitive region.

The details were revealed in documents seen by Unearthed, including the minutes of a meeting between Shell and the committee. The committee included representatives of a federal government ministry and local Indigenous people.

The minutes of a meeting at Shell headquarters in Calgary in 2014 obtained by a freedom of information request, note that a Shell representative said:

“Although Shell does not have any plans to develop the lease near Bylot Island, the lease does not expire and SHELL will not speculate if they would consider releasing the lease…

“SHELL indicated that if they were to give up the lease, they would need to get something back in return.”

Shell began to hold the permits in Lancaster Sound in 1971 and has not engaged in any drilling for oil there in what amounts to almost half a century. Legal experts have raised question marks over whether the permits have, in fact, expired by now.

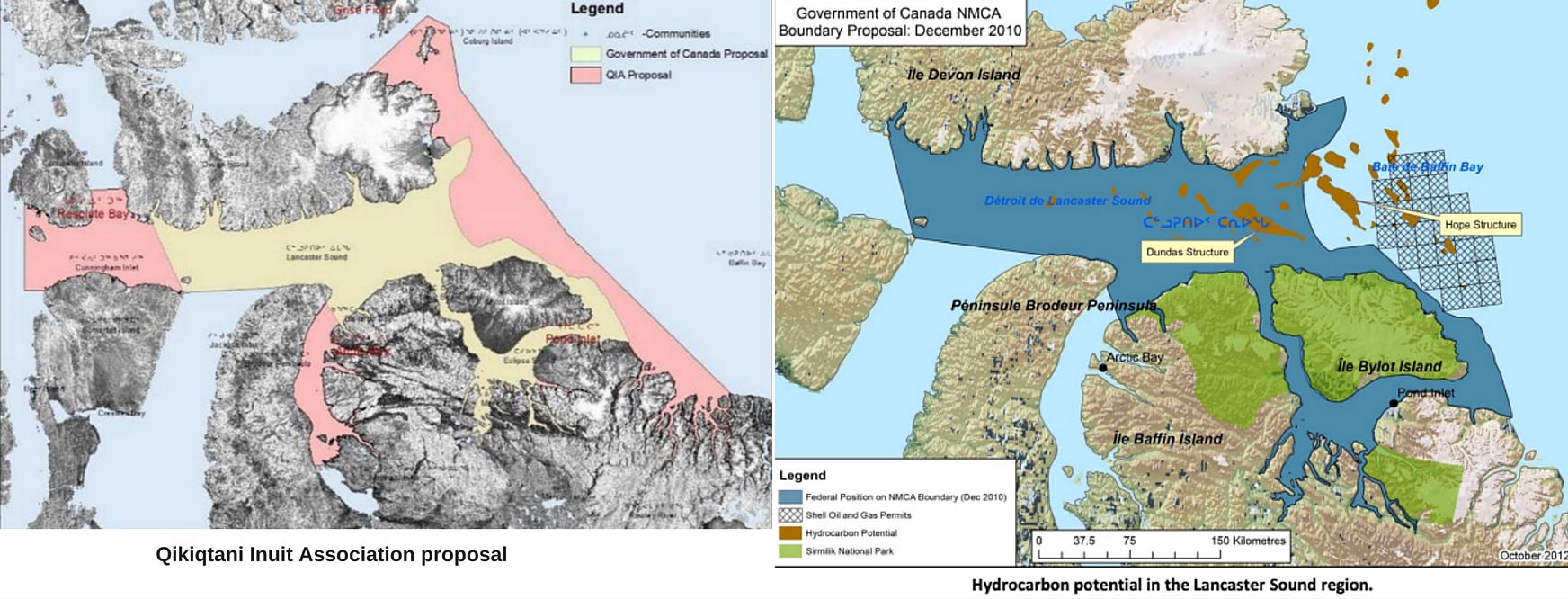

The permits (if indeed they exist) overlap with an area the Qikiqtani Inuit Association, which represents the inuit of the Baffin region, would like to see covered by a National Marine Conservation Area (NMCA). But they do not fall within the protected area put forward by the erstwhile Harper government in 2010.

Since then, Justin Trudeau has been sworn in as prime minister, and with President Obama announced a joint commitment to protect at least 10% of marine areas by 2020.

Trudeau also set out his commitment to repair the relationship of the Canadian government with Indigenous Peoples in December.

The Lancaster Sound NMCA steering committee, which includes the Qikiqtani Inuit Association and local Nunavut government, is currently preparing its feasibility report, which will include a boundary recommendation and is due out this year.

If the expanded version of the NMCA was implemented it would prevent Shell from drilling for oil in at least some of its permit sites.

The minutes suggest Shell would fight the move – unless it was compensated for the loss of opportunity to explore at the permit site.

Shell declined to comment when contacted by Unearthed.

Cultural and ecological importance

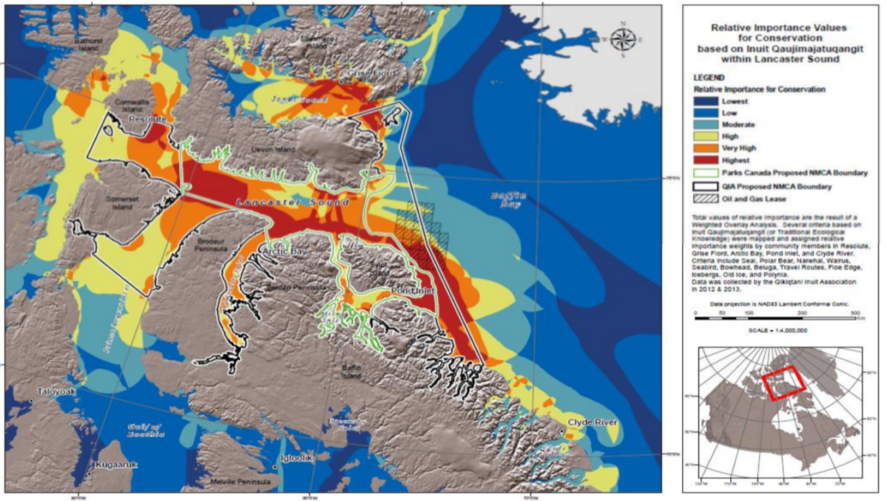

The Lancaster Sound blocks overlap with areas of ‘highest’ and ‘very high’ importance to the inuit community, according to research by The Qikiqtani Inuit Association (shown below).

The group spent two years mapping Inuit traditional knowledge for locations of cultural sites, currents and animal migration routes.

Lancaster Sound is a migration route for 85% the world’s narwhal and beluga whales. It’s also home to large numbers of bowhead whales, ringed seals, harp seals and walrus.

Seismic testing at Lancaster Sound?

At the consultation on the NMCA at its headquarters in 2014, Shell also said that whether it would swap the licenses for “something else” would be dependent on their ability to “appropriately assess the lease… with 3D and 4D seismic”.

Seismic testing is used to assess possible quantities of oil under the seabed – but it is a controversial technique because it gives rise to significant underwater noise pollution, which could harm cetaceans (whales and dolphins) in particular.

The surveying technique was prevented in Lancaster Sound by a major 2010 court ruling, after Justice Sue Cooper found that, “If the testing proceeds as planned and marine mammals are impacted as Inuit say they will be, the harm to Inuit in the affected communities will be significant and irreversible.”

Permits expired?

The permits could have expired in the late 1970s, but it’s a complex and controversial legal question. The permits were renewed in 1978 for a year, but the government appears to have no record of the permits being renewed in 1979, according to FOI research.

The Canadian government has said that the permits are not expired because they have no record of sending Shell official notices their permits were about to expire.

“More importantly, both industry and government have continuously treated the 30 Shell Permits as being valid and subsisting from the original date of issue to the present and will continue to do so in the future,” Michel Chénier, the director of the Petroleum and Mineral Resources Directorate at Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada, the department responsible for permitting, wrote in an email.

But Nigel Bankes, professor and chair of Natural Resources Law at The University of Calgary, told Unearthed: “My research on these permits suggests that they expired in the later 1970s because they were never properly renewed at that time.

“Even if that is not the case they have never been converted into exploration agreements or licences under the two successive relevant federal statutes the Canada Oil and Gas Act and the Canada Petroleum Resources Act.”

He adds: “I think that it is really up to Shell and the Government of Canada to provide some positive evidence as to why they think that these permits are still in force.”