No, a global coal comeback isn’t happening

Here we go again. The global coal industry is still reeling from the collapse of the 2011 coal export bubble, and already the financial media is suggesting that the latest uptick in international prices has turned coal into the ‘hottest commodity’ of 2016.

This sort of talk stokes the fantasies of global coal traders, who undoubtedly hope that the Asian coal bubble will re-inflate.

But they should be wary of the hype.

The last coal bubble – a boom and bust in international coal prices tied to short term trends in China – left the US coal industry in tatters, after industry executives sank billions of dollars on export projects that never saw the light of day.

False dawns

Take the Millennium Bulk Logistics Terminal in Longview, Washington as an example.

After Arch Coal went bankrupt and gave up its 38% share of the proposed project, and low cost producers wrote off their $58 million in export investments as well as shipping options at the proposed terminal, we thought the project must be on its last legs.

But the latest commentary on coal prices might add fuel to these terminal proposals once again despite the heavy losses investors have suffered on export projects, because the coal industry is a master at hyping up nonexistent bullish trends.

Do you remember how just a couple of years ago, China’s coal use was going to double this decade and continue ever upwards from there?

How about when Europe had a coal renaissance back in 2013?

When India’s imports were going to balloon to offset China’s shrinking demand in 2014?

When Japan’s nuclear closures were going to set of a coal resurgence?

You won’t find any evidence of these supposed coal booms in actual data, but they were uncritically reported by top-tier financial media, based on coal industry extrapolations from what turned out to be very temporary jumps in coal shipments and prices.

The fundamentals didn’t change.

Mythbusting

None of these narratives, however, were as contorted and bizarre though as the latest one: Chinese miners’ long, government-imposed holidays have supposedly turned coal into the ‘hottest commodity of the year’.

Here’s what’s really happening.

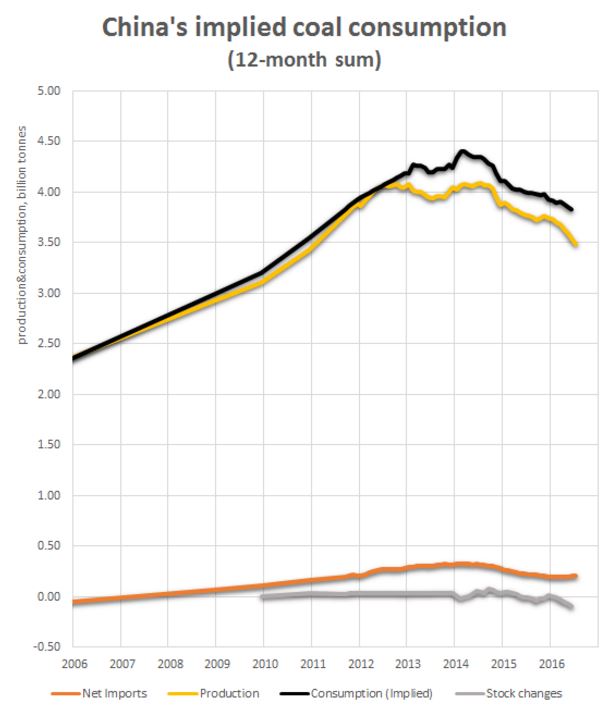

China’s coal demand is falling for the third year in a row, with the fall accelerating further in the first half of this year to 5% — despite government’s short-term stimulus propping up heavy industry demand.

As a result, imports are down by 50% from their 2013 peak.

India’s coal imports have continued to plummet this year after a steep drop of 15% in April-December 2015.

An amazing 30% of U.S. coal demand has evaporated since 2007, and a further 9% fall is expected this year.

China’s apparent coal demand has continued to fall rapidly; the uptick in imports has resulted from an even faster fall in coal production.

In the midst of this onslaught, the Chinese coal mining industry has been left with a tremendous amount of overcapacity — about 1,500 million tonnes per year, including mines that are still under construction.

The government is slowly starting to dismantle this overcapacity, with 250 million tonnes worth of capacity set to close this year and a lot of the under construction projects slowed down or put on hold, judging from a dramatic fall in investment into coal mining.

The industry is among the most indebted in China and keeps missing bond payments and delaying debt payments like the large miners in Shanxi, making the management of the problem a very tricky balancing act.

To slow down the piling up of bad debt, the government shored up the domestic coal price by forcing all major coal mines to cut allowed days of operation by 16% — to 276 per year.

This has caused a dramatic drop in coal production by 10% January-June, with the fall in production catching up to and overtaking the fall in consumption for the first time.

The key point here is that China’s tighter coal supply is not driven by capacity cuts or closing down mines, let alone an uptick in demand, it’s simply the government telling coal miners to take *very* long holidays.

The uptick

This measure caused China’s coal imports and international coal prices to jump temporarily, while staying in a completely different league than five years ago when coal actually was a hot commodity.

This jump has, however gotten quite a few analysts and reporters excited enough that they have started to talk about the blip like it indicates a major reversal.

Some believed that “government policies to nurse the Chinese coal sector back to health will support global prices for the foreseeable future.”

What it is though is a speed bump on a long, steep downhill. The reasons why should be easy enough to see:

1. The administrative nature of the measure means that it can be changed very fast as the situation changes, and indeed, Chinese media is already reporting that the government mulls lifting the output curbs for large, mechanised mines.

2. Increased imports are very much an unwanted side-effect of the government’s blunt-tool intervention, directly harming the desired impact of improved revenue and debt-servicing ability of domestic miners.

If the elevated imports were to continue, it seems very likely that the government would take additional measures to contain imports, as it did in 2014.

3. China still has at least one billion tonnes of coal mining capacity under construction, mainly in large, mechanised mines.

As some of this low-cost capacity comes online, it will worsen the existing structural oversupply on the domestic market and the entire Pacific coal market.

4. Too high a coal price would interfere with the government policy of eliminating coal mining overcapacity, by giving the producers more of an incentive to stay in business.

The central government is taking the overcapacity reduction targets very seriously.

5. The 276-day rule is the exact opposite of what the government’s longer-term economic strategy of ‘supply-side reform’ calls for – improving productivity and freeing up resources from non-productive sectors – as it in fact further substantially reduces productivity in the entire coal mining sectors.

As noncompetitive mines close and the overcapacity problem is alleviated, the short-term support will end, as noted in a recent Goldman-Sachs analyst note. A probable continued devaluation of the yuan will amplify this trend.

Simply put, the Chinese government’s interventions have no intention of saving the US export market or protect the seaborne coal trade. It’s all domestic for them.

So ignore the noise.

The global coal industry isn’t coming back. Seriously.

Graph based on official output and customs data, combined with industry data on coal inventories obtained from sxcoal.com.

Update Aug 25, 2016: An earlier version of this article incorrectly said that India’s coal imports were down 34% in 2015; this number refers to December 2015. Data and references have been corrected in the text.