International Energy Agency doesn’t have an answer for the energy water crisis

The global power sector could increase its water consumption 45% by 2040, according a new report by the world’s leading energy analysts.

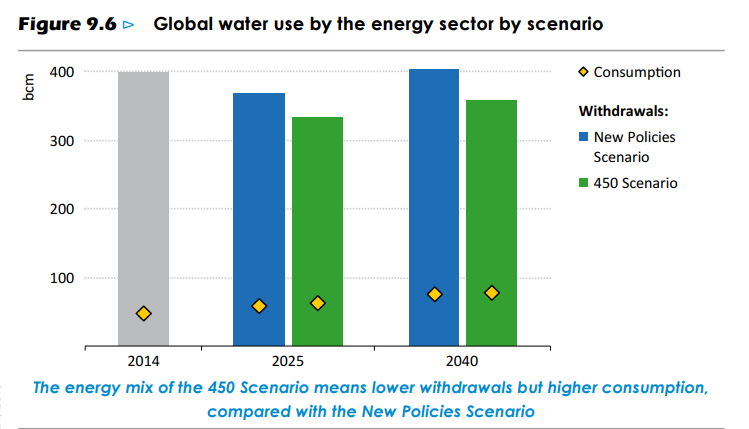

In both scenarios outlined in the latest World Energy Outlook, the International Energy Agency (IEA) sees water consumption by the energy industry increasing over the next 25 years, though water withdrawals will likely decrease.

Though water data specific to the power sector isn’t readily available, the text (page 363) indicates that the Agency’s 450 scenario would lead to dramatic water consumption increases, most likely in already arid parts of the world.

This significant jump in energy-related water use – caused by the continued use of coal and gas, as well as water intensive technologies like nuclear and carbon capture and storage – would exacerbate a developing water shortage crisis, one that could destabilise major regions and cause conflicts.

These fossil fuels are also contributing to climate change, which itself will feed water scarcity and worsen droughts.

World Energy Outlook

For the first time since 2012, the IEA’s annual report has produced an analysis of the water-energy nexus, and detailed the emerging water crisis facing the energy industry.

The IEA WEO 2016 identifies the challenge from using massive amounts of precious fresh water for cooling thermal power plants. It also highlights the particular challenge to countries like China and India, which have massive coal power plant fleets, in dry areas.

But the IEA analysis falls short on providing effective solutions to water crisis, instead envisioning the continued use of water-intensive fossil fuels, albeit with improved emissions efficiencies and an increase of technologies like CCS, and nuclear power, which have very high water demand.

The Agency admits that reducing carbon emissions does not necessarily bring water savings.

The great water grab

Earlier this year Greenpeace released its first-of-a-kind global assessment of water demand from coal industry. The results show that world’s coal power plants consume water enough for basic water needs of 1 billion people.

This water is used mostly for cooling the power plants. Like the IEA, Greenpeace identified the special challenge faced by China and India.

Nearly half of China’s coal power plants are in extremely water stressed areas of the country, where water is withdrawn faster than it is replenishing, in effect risking running out of water. But the government is still planning to increase coal power capacity, half of it in those same dry areas.

In India severe drought has already reduced amount of cooling water available, which has even stopped many power plants from operating. Indian power companies lost revenue up to $560 million in first seven months of this year, according to our estimates. The country would also enjoy huge water savings if it replaced coal plants with wind and solar power, technologies with very little water demand.

Policy response

The water challenge requires comprehensive policies from the energy industry since the two sectors are so intertwined.

As water is fast becoming one of the bottlenecks of energy production in the warming world, the best solutions would use one investment to tackle both CO2 emissions and water at once.

A different approach risks prioritising one environmental hazard over the other, with possible CO2 reductions doing little to improve water supplies. IEA seems to have fallen into this trap.

Wind power and solar PV provide excellent opportunities for this double benefit, as they have both very small water and carbon footprints.

Even if the IEA recommends that countries integrate planning of water and energy policies, they themselves have not done this in their scenarios.

In its 450 scenario, with fastest rate of cutting carbon emissions, water consumption by power sector could increase by 45% between 2014 and 2040 — because of technology choices the IEA has made.

Instead of going all-out on expanding the most water efficient technologies wind and solar, the IEA insists on increasing water intensive CO2 reduction measures, including nuclear power, carbon capture and storage, concentrated solar power and biofuels.

It even still sees massive investments in coal and gas power plants, which might be a bit more efficient, but still have significant water footprints and significant carbon emissions. It’s little wonder then that they IEA CO2 reduction and water savings don’t really work together.

Harry Lammi is a energy analyst at Greenpeace East Asia