China’s distant water fishing industry is now the largest in West Africa

Photographer Liu Yuyang spent a month on board Chinese boats in West African waters, and with communities on land, documenting life in the fishing industry

China’s distant water fishing industry is now the largest in West Africa, with more than 400 fleets operating, producing a £340 million catch every year, according to documents published by China’s Ministry of Agriculture.

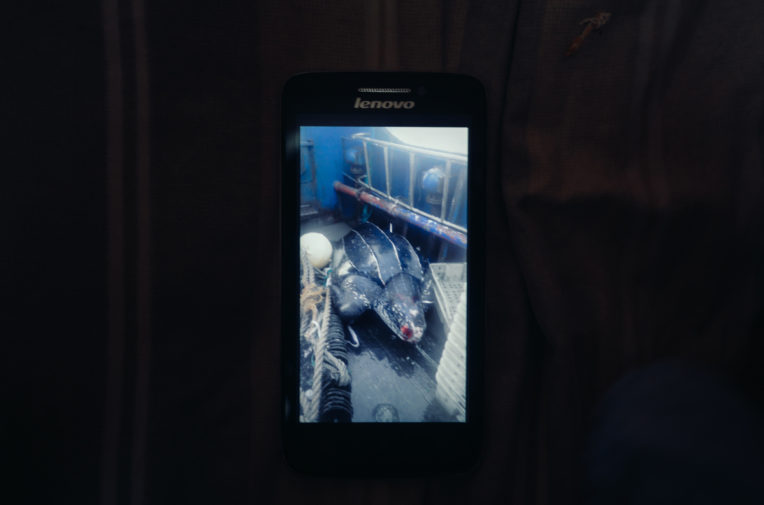

The majority of the boats use bottom trawling, an extremely destructive form of fishing which catches anything in its path – and a major reason for the depletion of fish stocks in China’s domestic seas.

Greenpeace commissioned a photographer to spend a month on boats and land in west Africa, documenting an industry that appears poorly regulated – and the lives affected by it.

In May 2015 Greenpeace exposed 74 Chinese distant water fishing vessels for fishing in prohibited waters and falsifying their vessel tonnage.

Between 2001-2006 and 2011-2013 a total of 183 ‘illegal, unreported and unregulated’ (IUU) cases involving Chinese vessels in west Africa were documented.

Overfishing

The seas around the west African coast are some of the richest in the world, attracting a global industry that provides 3.6 million tonnes of fish every year.

Since the 1950s, a total of 47 nations have had distant water fishing operations in the area.

Over 70% of China’s boats in Africa are harvesting the seas off the coasts of Senegal, Mauritania, Guinea Bissau and other west African countries.

Decades of intense exploitation of west Africa’s seas, by all nations operating in the area, have resulted in over 50% of fishing resources being overfished.

Working conditions

The arrival of the Chinese fishing industry has also had a big societal impact on west African countries.

First of all, 70% of Senegalese animal protein intake comes from fish. So any depletion in stocks has an impact on the Senegalese diet.

Secondly, Chinese boats have become both a source of competition and a source of better paid employment for the local fishing industry.

In Senegal, a total of 15% of the working population work in the fishing industry. Of these 100,000 workers, 90% work in traditional artisanal fishing.

As fish stocks have come under greater pressure from foreign distant water fishing vessels, these fishermen have been forced to travel further and further out to sea to make their catch.

The remaining 10% of the Senegalese workforce employed in the fishing industry work on foreign distant water fishing boats. Here they earn a comparatively high wage of up to CFA Franc 100,000 (£129) per month.

Chinese fishermen are also attracted to their country’s distant water fishing industry by the comparatively high salary. Staff aboard a China Fujian Distant Water Fishing Ship typically earn between RMB80,000 to RMB300,000 (£9,300 to £35,000), substantially higher than a typical wage of RMB50,000 to RMB200,000 (£5800 to £23,000) in China’s domestic fishing industry.

Of the 20-man crew, seven are Chinese and 13 are from local west African countries.

The fish industry is not only confined to the sea, however. Demand for fish meal, used as animal fodder and feed for aquaculture and industrial farming, is booming in China, driven by the growing global meat industry.

Fish meal companies are attracted to Mauritania due to the government’s encouragement of the industry and the region’s sardine resources, a protein-rich fish which is ideal for fish meal.

The Lem Fishmeal Factory in Nouadhibou, Mauritania’s second largest city, is one example. It is one of at least 20 fish meal factories in the town, half of which are Chinese owned. The factories are the backbone which supports the town’s 1,000-strong Chinese community.

The fishing industry in west Africa is just one example of China’s new role as a force shaping 21st century Africa. As China’s influence across Africa grows, pressure will increase on resources and communities across the continent.

Tom Baxter and Pan Wenjing are an international communications officer and senior forest and oceans campaigner at Greenpeace East Asia.