Analysis: How China’s heavy industries became ‘too big to fail’

2016 was supposed to be the year when China truly cracked down on steel overcapacity.

The government set targets to eliminate up to 150 million tonnes of steelmaking capacity over the next few years, more than the total capacity of any other country in the world.

Instead, it ended up playing whack-a-mole.

For almost every steel mill that the government closed down, another previously-closed mill got restarted or a newly built mill came online.

Want stories like this in your inbox once a week? Sign up here

Steelmaking capacity equal to the total capacity of Germany, the world’s 6th largest producer, was restarted.

On the other hand, most of the eliminated capacity was already lying idle due to low steel prices and oversupply.

Obstacles to reform

Overcapacity in sectors such as steel, coal mining and coal-fired power is not an isolated problem, but an almost unavoidable result of China’s past economic model.

An excellent new analysis by Ning Zhu, the Deputy Director of Chinese National Institute of Financial Research, argues that implicit government guarantees are a key driver of overcapacity in China.

Investors and banks expect guaranteed returns, which leads to excessive and risky investments.

This overcapacity then becomes too big to fail, leading the government to salvage the overcapacity industries by creating demand, and reinforcing the expectation of guaranteed returns.

The only way to break the cycle is to accept losses and allow some of the over-leveraged enterprises to fail.

This would mean taking many of the zombie companies out of life support and into bankruptcy.

In 2016, after two years of painful slowdown in heavy industry sectors, the impulse to preserve stability at the expense of reform and environmental protection proved stronger.

These impulses were all too apparent in local government efforts to support local steel mills and keep them operating.

‘Unbalanced economy’

Almost exactly 10 years ago, Chinese premier Wen Jiabao famously called the country’s economy ‘unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable’.

Nowhere are these ‘four uns’ as apparent as on China’s steel sector.

Read: China ramps up steel capacity despite closures

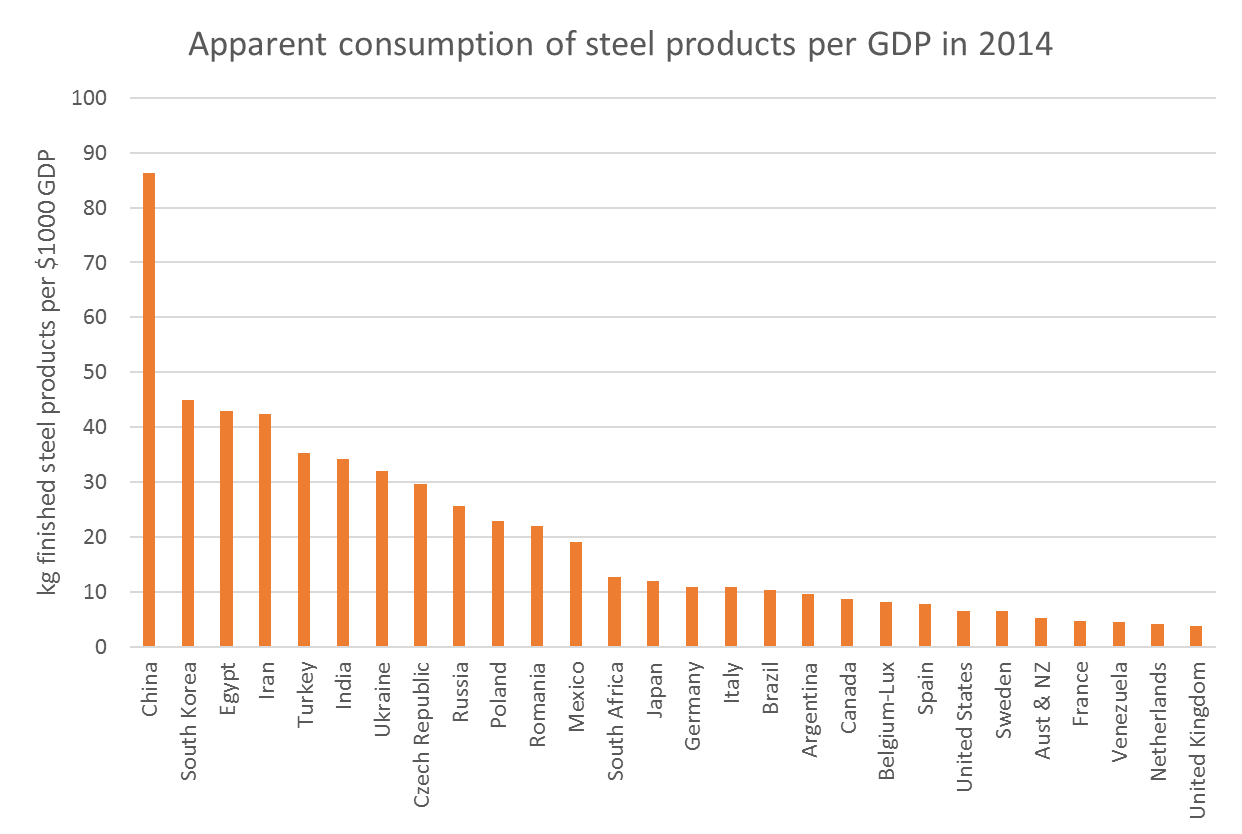

The country uses twice as much steel per unit of GDP than any other world economy – including other emerging economies that are also experiencing rapid urbanization and economic development.

Steel is also by far the most energy and emissions-intensive out of China’s major industrial sectors.

Steel is at the heart of the vast amount of real estate and infrastructure construction that dominates China’s economic structure.

After decades of frantic construction, investments are no more driven by need for more roads, airports or cities, but rather by GDP targets and attempts avoid a potentially painful adjustment to lower construction volumes.

However, this adjustment has the potential to resolve not only financial and economic problems, and benefit Chinese consumers, but to also drive down China’s air pollution and CO2 emissions.

One of the main benefactors will be the Beijing region, where the industry is centred.

Beijing under siege

Beijing’s air pollution (PM2.5) in the first five weeks of 2017 was almost twice as severe as the year before.

While a lot of this is down to natural variation, it accentuates a worsening trend in air quality that has been observed since stimulus started driving up heavy industry output in the second quarter of 2016.

Beijing is surrounded by steel industry bastions on three sides, south, east and west.

The Hebei province that encircles Beijing almost completely makes more steel than any other province and and country outside China.

Steelmaking in Hebei is also particularly dirty, emitting twice as much particulate matter per tonne of output than the number two producer, Jiangsu, according to official data.

This concentration of steel industry around Beijing only became more pronounced in 2016, with three fourths of the factory restarts taking place in just three of the provinces neighboring the city.

Pain ahead

Chinese analysts say increasing demand for steel in the second half of 2016 was an anomaly that’s unlikely to be repeated in the coming year, as government stimulus wears off.

This could be setting the steel industry up for renewed pain, as high operating capacity hits the wall of falling demand, lowering prices and profitability both at domestic and international markets.

The imperatives of cleaning up the air, tackling overcapacity and putting the economy on a sustainable path mean that the government will have to increase overcapacity elimination targets.

However, with China’s steelmaking capacity standing at approximately 1,100 million tonnes and demand at 700 million tonnes, oversupply is likely to persist for years to come.

Reality bites.