Global carbon dioxide emissions rise as China backslides

Despite Donald Trump's rise to power, data shows that the European Union is performing no better than the US as emissions rise worldwide

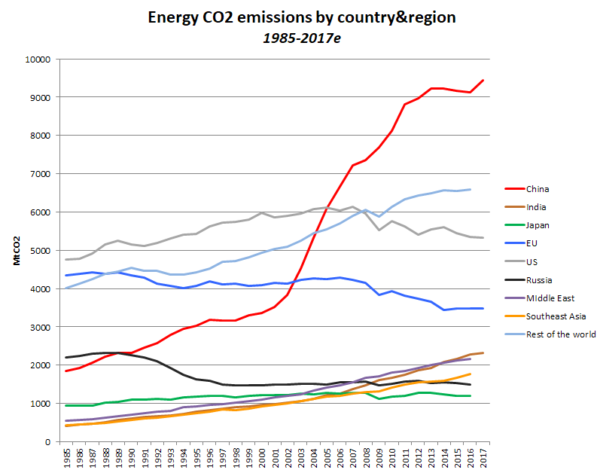

Global emissions have risen by 2% in 2017 after three years of near stagnation, according to a new forecast.

The leveling-off of global emissions was largely driven by China, where emissions were flat from 2013 to 2016 but are now forecast to rise by 3.5% after efforts to boost economic growth.

The rise may prove temporary. A return of severe air pollution to Beijing and surrounding cities has led to factory closures and suspensions of new coal plant construction.

By contrast, India is projected to see a sharp slowdown in emissions growth, falling from 6% last year to just 2% in 2017, according to data from the Global Carbon Project, an international research consortium.

In the US and EU the pace of emission reduction slowed, failing to offset the increase in carbon dioxide production by emerging economies, according to the forecast.

In the US, emissions are forecast to fall by just 0.4% as renewable energy partially replaced natural gas in power generation. EU emissions are forecast to fall by 0.2%.

Uncertainty around the forecasts for the US and EU makes it impossible to know for sure which of the economic blocs will post a larger fall.

It means that US emissions cuts could even those of the EU, despite the election of Donald Trump and the country’s withdrawal from the Paris climate deal.

The analysis comes as governments meet in Bonn to discuss new measures to curb global climate change.

China emissions rise

The rise in China’s emissions was the main cause of the global increase. It came after provincial governments in the country turned to major industrial stimulus in an effort to boost growth and employment.

State-backed support for heavy industry saw steel production rise by 5% and coal generation go up by 6%. Diesel use also increased, driven by industrial demand.

At the same time China saw a significant fall in output from its hydroelectric plants, which are heavily influenced by variations in weather patterns.

This decrease offset rises in other forms of renewable energy and the increased connection of wind and solar plants to the grid.

However, the return to coal-fuelled economic growth has led to controversy in China.

Serious air pollution has returned to Beijing and other major cities, while economists have warned about excess capacity in both the coal and heavy industrial sectors leading to risks of bankruptcies and bad debt for the country’s state-owned banks.

The concerns led to a dramatic policy turnaround towards the end of the year, with factories closed and new coal plant construction cancelled or put on hold.

The Global Carbon Project notes: “Industrial growth is starting to slow down again, hydro output is picking up again, and several political signals (caps on winter coal use, speeches that signal greater acceptance for slower growth, etc) suggest that emissions growth will slow down by the end of this year.”

US and EU disappoint

The EU and the US both saw emissions fall at slower rates than in previous years according to the study, with the EU doing no better than the US under Trump.

Emissions in the EU are forecast to fall by just 0.2% as carbon dioxide production in Germany – the host of the current climate talks – looks set to rise for the second year in a row.

In the US emissions fell by slightly more – 0.4% – as more expensive natural gas was replaced by wind, solar, hydro and some coal.

US wind generation increased by 8% and solar power generation rose by 36%, albeit from a far smaller base.