China plans to cut coal heating again, but can it avoid another crisis?

Attempts to cut back on coal use have improved air quality, but reportedly left millions without proper heating

China is planning to cut coal used for heating by a third within four years, even as it recovers from a winter fuel crisis that, at its peak, reportedly left millions without proper heating.

The new strategy is part of its bid to drive down winter air pollution.

The aim of the 2017 plan was to curtail small-scale coal burning by shifting 3 million households in northern China onto cleaner heating, but over ambitious implementation by local governments took this figure to 5.5 million in reality.

The new clean heating plan, announced shortly before Christmas, sets targets to shift an equal number of rural households from coal to cleaner heating every year for the next four years.

In addition, an estimated 40 million households that are supplied by district heating – central generators that provide for whole communities – will also be shifted away from coal.

If successful, it will eliminate coal as the heating source for about 63 million households by 2021, replacing 140 million tonnes of coal.

That’s the same as Germany’s total annual coal consumption.

But this winter’s heating crisis left many people in rural areas without gas for cooking, heating or hot water.

So how did the crisis happen – and can another one be averted?

Indoor pollution

While the smog in Beijing often grabs the headlines, household fuel burning is the largest source of wintertime air pollution in northern China and is a major health hazard for people in rural areas.

Coal is by far the main source of all heating in China, providing 83% of heat in 2016, according to a Greenpeace analysis of government data.

Indoor air pollution, mainly caused by coal-burning, was estimated to be responsible for 1,700 premature deaths a day in China in 2016. Outdoor air pollution was responsible for 2,900 premature deaths per day over the same period.

The improvements in air quality brought about by this winter’s action plan eliminated around 6% of total household coal use in China. This will likely reduce the number of premature deaths from indoor air pollution by 30,000 per year.

A heating crisis

The tempered smog was cold comfort for many people, particularly in rural areas.

The large scale push to eliminate small-scale coal burning in provinces surrounding Beijing failed to install homes with gas heaters or pipes in time, leaving them without heating in sub-zero temperatures.

Over winter, the area was struck by a serious gas shortage, leading to gas supply being stopped regularly.

Many residents also found their heating bills increased dramatically, despite government subsidies, as gas and electricity are more expensive than coal.

A lack of reliable information about the heating crisis forced the government to dispatch staff to carry out doorstep inspections of people’s homes.

The government responded with a partial reversal of the coal ban for locations where alternative heating had not been installed. However, a lot of households had their coal stoves removed as a part of the campaign and many towns continue to be plagued by lack of gas.

So what went wrong?

The shortage was caused by several factors.

Demand from industry surged before the heating season, pushing consumption up by a fifth, while household gas and coal demand resulting from the switch was significantly underestimated, due to persistent under-reporting of small-scale coal use.

At the same time, small industrial coal burners were being eliminated by a government policy drive and overzealous local officials implemented the coal ban in larger areas than the central government intended.

A lack of financial support and incentives also meant that some cities were very late to implement the switch, creating problems with gas transmission and storage capacity.

Will anything change?

The clean heating plan makes changes in attempt to prevent another winter crisis.

First and foremost, it relies much less on gas as a substitute for coal.

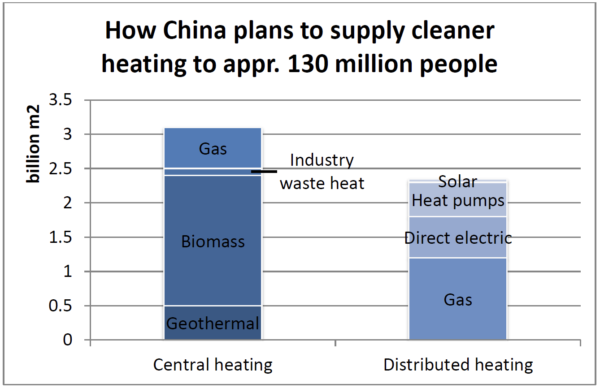

While the 2017 plan used gas as an alternative for 80% of demand, the new plan cuts this to one third. Biomass, heat pumps, direct electric heating and geothermal make up the rest.

The plan also sets ambitious targets for energy efficiency, aiming to reduce average heating energy demand by 30%, through measures such as improved insulation.

Central government will need to use taxes and subsidies to make the shift more feasible and economically attractive.

Meanwhile, local governments could use China’s new environmental tax to incentivise gas and electric companies to invest in gas transmission, storage, energy efficiency and heat pumps. But at the moment it’s not clear if such measures will be taken.