The Raúl Rojas open-pit mine seen from Paraghsa, one of the worst affected neighbourhoods in Cerro de Pasco. The pit stretches for 1.2 miles and is over 1,000 feet deep. Photo: Ricardo Martínez

The city built around a mine

With mining activity set to expand around Cerro de Pasco, the city's residents continue to struggle with the effects of historic pollution

The city built around a mine

With mining activity set to expand around Cerro de Pasco, the city's residents continue to struggle with the effects of historic pollution

The Raúl Rojas open-pit mine seen from Paraghsa, one of the worst affected neighbourhoods in Cerro de Pasco. The pit stretches for 1.2 miles and is over 1,000 feet deep. Photo: Ricardo Martínez

Sunmi is a 10-year-old girl who lives with her family in Cerro de Pasco, the self proclaimed ‘mining capital’ of Peru. Her home backs onto a giant pile of mining waste. According to her family, she has a mental age of four and her health problems are consistent with high levels of lead in her blood.

In a city that has been dealing with historic pollution from mining for years, health problems associated with lead and other heavy metal poisoning are part of life. At least 2,000 children in the Pasco region live with chronic heavy metal poisoning, according to a report by local officials published last year.

The company which operates the mine in Cerro de Pasco, Volcan Compañia Minera, says that pollution in the area stems from previous operations.

And now with Volcan, which counts commodities giant Glencore as its major shareholder, looking to develop new mines in the surrounding area, the city is once again in the spotlight.

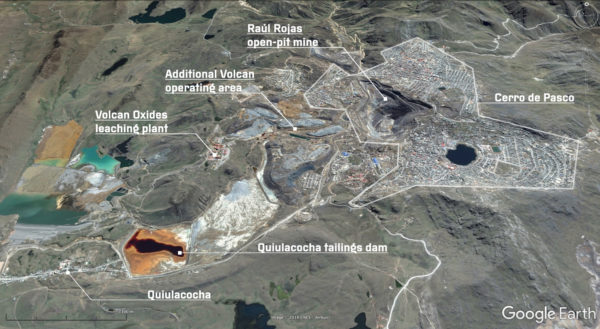

Perched 4,300m above sea level in the Andes, Cerro de Pasco is literally built around a major zinc and silver mine. The industry has dominated the city ever since Spanish colonists first found silver here in the 17th century.

It’s a race between countries in the region. They are relaxing rules in order to compete in luring mining investments

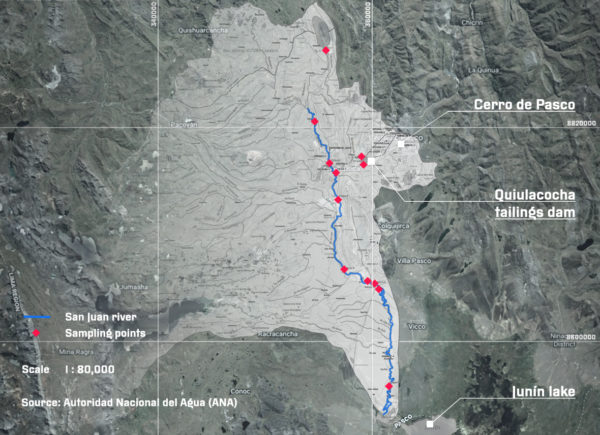

Since then the area has become synonymous with pollution and environmental damage. Government and private researchers, have found that mining waste from the city affects a water supply for over 100,000 people.

The Peruvian National Water Authority found in 2013 and 2015 that the full length of the San Juan subbasin – a 936km2 watershed that follows the San Juan river from Cerro de Pasco south to Junín Lake – contains at least four heavy metals in concentrations that exceed World Health Organisation (WHO) standards, including lead and arsenic.

Peru’s heavy metal concentrations allowed in water are higher than WHO’s. The national limit for lead in water in Peru is 0.05mg/L while WHO is 0.01mg/L. The arsenic limit in Peru is 0.05mg/L while WHO is 0.01mg/L.

Lead exposure can cause congenital malformation, neurodevelopmental disorders and chronic epistaxis (nose bleeds), to which children are particularly vulnerable. Local authorities in the Simon Bolivar district where the mine is based say these are common afflictions among children in the city.

Volcan, which operates the Raúl Rojas open-pit mine which dominates Cerro de Pasco, intends to expand nearby. Shuco, a mining prospect three kilometres from the city, has already been approved by Peru’s energy ministry and is currently in the planning stage.

Peru’s top zinc and silver producer, Volcan currently processes stockpiled ore from the Raúl Rojas open-pit mine.

Apart from yielding zinc from processing, stockpiles of ore are worked to recover silver and gold at an oxides leaching plant – it processes over 2,500 metric tons per day now and through 2017, it produced 3.7 million ounces of silver.

Asked to comment on this story, both Volcan and Glencore told Unearthed in identical statements that pollution in the area was from historic mining activity and pointed to official studies by the Peruvian government showing that air and water quality is within national limits in Cerro de Pasco, while heavy metal pollution in soil does not exceed “permissible levels”.

The statement read: “In September 2017, studies by the Peruvian Ministry of Health demonstrated that the water in Cerro de Pasco is not contaminated by heavy metals and that the air quality is within the limits established by the National Standard for the Environmental Quality of Air (ECA). According to the studies, mining activity is not contaminating either the water or the air in Cerro de Pasco.

“In the case of soil, heavy metals were found to exceed permissible levels. The government plans to study these findings in more detail to determine why this is the case. Volcan’s own monitoring confirms this finding. In addition, Volcan is actively supporting government efforts to help children and families affected by contamination in Cerro de Pasco.”

Unearthed went to both Volcan and Glencore to point out that Peru’s national standards for heavy metal concentrations in water are weaker than WHO’s recommendations and asked if the companies would like to clarify their comments accordingly, but both declined to comment.

The non-profit Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) gave Peru a ‘satisfactory’ grade (62 out of 100) in its governance index last year, but Carlos Monge, NRGI’s Latin America director, worries that the government’s ambition to lure lucrative mining projects to Peru could see environmental standards weakened.

“It’s a race between countries in the region,” he says. “They are relaxing rules in order to compete in luring mining investments.”

It is not yet clear what impact the election of new President Martin Vizcarra – a political novice who once led a series of protests against the unequal distribution of mining levies in his home district of Moquegua – will have on the situation.

Twice in the last three years, local authorities of the Pasco region’s Simon Bolivar district have held ‘sacrifice marches’, leading residents on a 250km walk to Lima to confront central government over years of inaction.

A project to bring potable water to all citizens in Cerro de Pasco was proposed over four years ago. However, it is yet to be fully developed by the Regional Government of Pasco, which is headed by Teodulo Quispe, a former operations manager at Volcan’s Cerro de Pasco mine. The governor’s office did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Peru’s environment ministry declared an environmental state of emergency in 2012, but local officials complain that little has changed since. The Peruvian health ministry state that a detox clinic and toxicology lab will be installed in Cerro de Pasco by 2020.

For the time being, children like Sunmi will have to live with the consequences of living in Peru’s mining capital.

Reporting for this story was made possible by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

Additional reporting by Joe Sandler Clarke, multimedia editing by Georgie Johnson.