In photos: The Great Australian Bight, a pristine environment threatened by oil drilling

Photographer Michaela Skovranova travelled to the coast of southern Australia to capture the animals that call this unique marine ecosystem home

Over 85% of species found in the Great Australian Bight are unique to this one stretch of ocean along the southern coast of Australia. The vast area is home to 36 different whale and dolphin species, and its waters contain more endemic marine diversity than the Great Barrier Reef, according to groups like the Wilderness Society.

But as well as being a wildlife hotspot, the Bight has also been targeted by the oil industry.

Norwegian state-owned energy giant Statoil, now Equinor, intends to drill for oil in the area in October next year.

At its AGM today in Stavanger, the company will be renamed ‘Equinor’ – a name that supports the firm’s “always safe, high value and low carbon strategy”, according to its website. Despite the rebrand, concerns persist around Equinor’s plans in the Bight.

Equinor insists that by the time it starts drilling, it will have spent over two years planning the project and consulting with regulators to ensure it is safe.

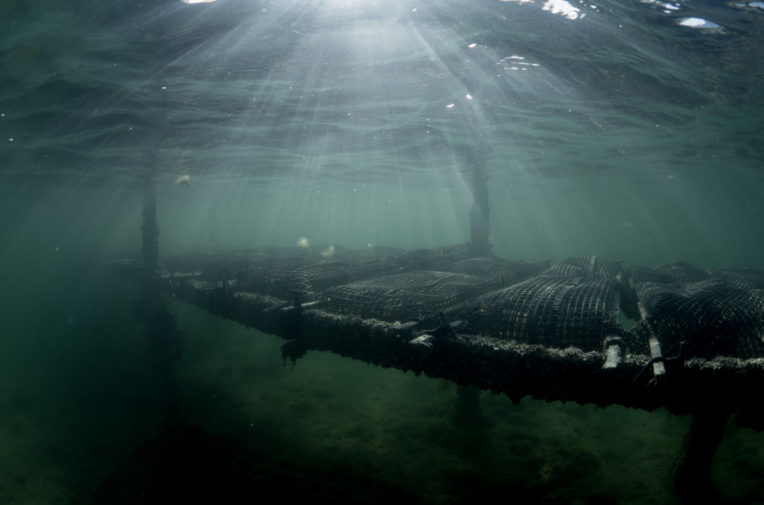

But many green groups and local politicians fear that oil activity in the region could harm wildlife and cause environmental destruction that would affect local industries, including fishing, oyster farming and tourism.

In December 2016, BP abandoned plans to drill in the Great Australian Bight, which is famous for harsh winds and strong currents. At the time, Australian regulators said that the company had failed to provide information on oil spill response plans and the risks drilling posed to nearby marine reserves.

US firm Chevron gave up on a drilling bid in October last year.

Documents obtained by ClimateHome last month showed BP’s plan to drill in the Bight could have exposed more than 450 miles of coastline to risk of contamination from a possible oil spill.

Statoil/Equinor became the operator and 100% equity owner of two of the four permit zones it had previously shared with BP in July 2017.