‘A monstrous disposable industry’: Fast facts about fast fashion

From fossil fuels to water and pesticides, the fashion industry is coming under increasing scrutiny for its impact on the planet.

As the fashion industry continues to grow, the strain it puts on the environment intensifies, with even English fashion designers like Phoebe English describing it as a “monstrous disposable industry”. On the eve of London Fashion Week, we reviewed the evidence amassed in the Environmental Audit Committee’s investigation into fast fashion.

Is fast fashion the new single use plastic?

The UK is the epicentre of fast fashion in Europe, with each person buying an estimated 26.7kg of clothing every year, compared to an average 15.6kg for people across Germany, Denmark, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden.

But with that growth in consumption comes a growth in waste with fashion items becoming – effectively – another type of single-use product.

When we buy polyester clothes, we’re wearing fossil fuels

The proportion of synthetic fibres, such as polyester, in our garments has doubled since 2000, rising to 60% in 2019. These fibres are produced from oil. One polyester shirt has a 5.5kg carbon footprint, compared to just 2.1kg for a cotton shirt. If demand continues to grow at the current rate, the total carbon footprint of clothing would grow to 3,978 mega tonnes by 2050. This is equivalent to almost double the carbon emissions of India in 2018. It would mean that by 2050, the industry would monopolise 26% of the global carbon budget required to keep the planet within 2 degrees of warming.

Fast fashion has accelerated the traditional business model in the fashion industry, encouraging people to buy more clothes by offering low prices and increasing the number of new seasons per year. However, the growing demand fuelled by fast fashion takes a toll on the environment.

Flying has nothing on the carbon footprint of the fashion industry

Every year, global emissions from textile production are equivalent to 1.2 billion tonnes of CO2, a figure that outweighs the carbon footprint of international flights and shipping combined. Looking beyond textiles production to the environmental impact of clothes washing and how clothes are discarded conjures an even more bleak image: an annual CO2e footprint of 3.3 billion tonnes – equal to 8% of global greenhouse gas emissions. If the fashion industry were a country, its emissions would rank almost as highly as the entire European continent.

Cotton is a thirsty fibre

Increasing reliance on cotton clothing might seem like a neat solution to the rampant carbon consumption driven by synthetic fibres. However, although cotton has a lower carbon footprint, cotton production requires significantly more land and water than its synthetic counterparts. The amount of water used in cotton production has reached 93 billion cubic metres of water per year, with 10,000 – 20,000 litres of water needed to make just 1kg of clothing. This places immense strain on the water supplies in Central Asia, China and India, countries which are already contending with water scarcity linked to climate change.

The land and water that is not usurped by the cotton fields is often heavily polluted by fertilisers and pesticides. Globally, cotton fields account for 2.4% of cultivated land, but consume 6% of pesticides and 16% of insecticides. Not only can this have a detrimental impact upon the health of cotton pickers, insects, birds and animals, but it also means that as water is redirected to the cotton fields, soils acidify and become increasingly barren.

In Central Asian countries, the pressure to meet global cotton demand has birthed an “ecological, economic and social disaster,” the Aral Sea has been reduced to desert in some areas.

Clothes manufacturing uses land which could otherwise produce food or absorb carbon

A collection of environmental problems are giving the fashion industry a bad reputation, from chemical pollution associated with cotton production and textile finishing to the adverse impact of microplastics and the deforestation of ancient and endangered forests for rayon and other cellulosic fibres. Globally, only the housing, transport and food sectors outweigh the scale of the fashion industry’s impact on land, with the amount of land it uses projected to increase by 35% by 2030. This would mean that an extra 115 million hectares – an area almost five times the size of the UK – would be diverted from conservation, carbon capture and our global food supply, indirectly driving fashion’s contribution to climate change.

Some fabric is never worn and the clothes that make it to market aren’t actually worn all that much

The forever shifting goal posts of fashion means that the lifespan of clothing can be very short. Globally, it’s estimated that $500 billion of value is lost every year through underwearing and a failure to recycle clothes.

Between 2000 and 2015 the number of times an item of clothing is worn decreased by around 36%. In the UK, the average person owns 115 items of clothing, but 30% of these clothes have not been worn within the past year.

In the UK alone, £140m worth of clothing goes to landfill every year. Moreover, some fabrics are never worn; the Environmental Audit Committee found that 15% of clothing fabric is wasted at the cut-off stage of production, before it even reaches stores.

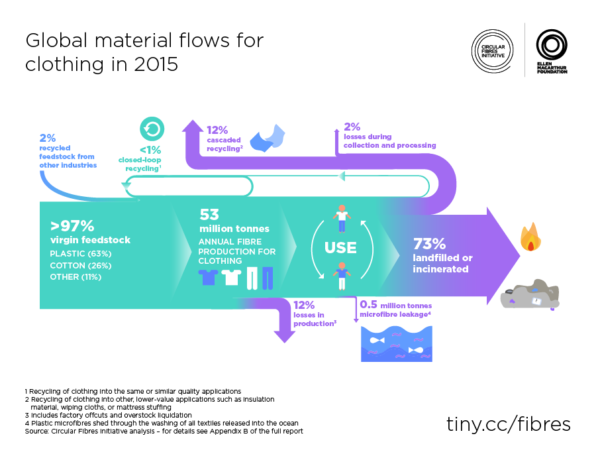

The circular economy is still a long way off

In the UK, only around a third of the 650,000 tonnes of discarded clothes given to charity or other circular fashion initiatives are resold, with the rest being sent off to textile recyclers.

Despite what we all might wishfully hope, textiles recycling centres do not magically transform our old clothes into new trendy items. In reality, less than 1% of pre-consumer and post-consumer textiles are recycled into new clothing.

The recycling process often damages and shortens textile fibres, reducing the number of viable uses for recycled textiles. Instead of going on to become a new hotly desired outfit, as much as 13% of recycled textiles end up being downscaled into fibre cloths or mattress insulation. The heavy toll of recycling means that most textiles can only be recycled once.

As a result, it is often cheaper to use virgin fibres for clothes production than it is to recycle fibres from old clothes.

And what happens to the clothes that are not resold or recycled? The remaining clothes, a figure that accounts for around 73% of those received by charities and textile sorters worldwide, are either sent to landfill, to the tune of £82m every year in the UK alone, or incinerated.

Brands aren’t scaling back production as much as they’d like you to think

The Sustainable Clothing Action Plan (SCAP) encourages brands to become more environmentally conscious. With targets focusing on the amount of water, carbon emissions and waste generated during clothes production, the plan was designed to curb the fashion industry’s exploitation of environmental resources.

However, although SCAP appears on course to meet its 2020 water and carbon targets, reduction goals are set per tonne of clothing. This means that the founders of SCAP, the Waste & Resources Action Programme (WRAP), measures its success based on the eco-efficiency of production, not the net growth of the industry. A broader assessment of the fashion industry reveals that UK clothing consumption has actually grown in the years SCAP has been active, increasing from 950,000 tonnes in 2012 when the initiative came in to 1,130,000 tonnes in 2016.