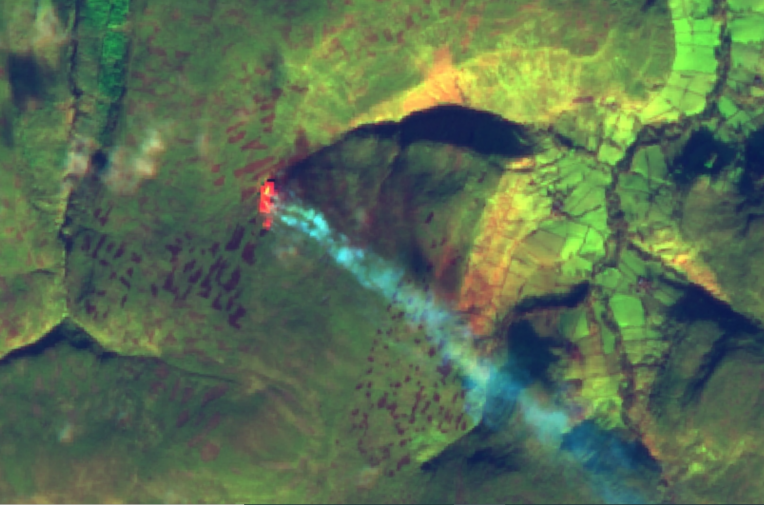

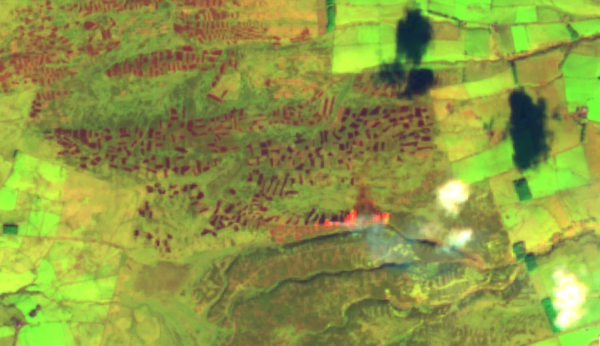

A fire on peatlands in the North York Moors national park is spotted by a satellite on 19 January 2022. Image: Sentinel Hub

Satellites reveal widespread burning on England’s protected peatlands, despite government ban

Investigation reveals evidence of more than 250 fires over six months. Dozens may have been illegal under new rules

Satellites reveal widespread burning on England’s protected peatlands, despite government ban

Investigation reveals evidence of more than 250 fires over six months. Dozens may have been illegal under new rules

A fire on peatlands in the North York Moors national park is spotted by a satellite on 19 January 2022. Image: Sentinel Hub

Above Grimwith reservoir’s sparkling blue waters in the Yorkshire Dales lies a habitat that the government describes as one of England’s “national rainforests”. It is a boggy moor, packed full of peat, soil so wet and rich with plant material that it may store more carbon, acre for acre, than tropical rainforest.

But today the land is scorched dry and crunchy underfoot. Blackened spikes of dead foliage protrude upwards, embers from a recent fire. It was burned to encourage growth of the fresh young shoots of heather on which grouse like to feed – grouse which will later be killed by shooting parties.

The fire here was set in spite of – and in apparent contravention of – a partial ban on peatland burning introduced by the government last year, in the run-up to the Glasgow climate summit.

We came here to test the peat depth, as part of a major investigation into the impact of this new ban. The government says its new rules are intended both to protect England’s blanket bogs – a delicate habitat of international importance – and to help the UK hit net zero carbon emissions by 2050. These peatlands are the biggest natural carbon store on UK land. Rotational burning dries the peat and erodes its ability to keep carbon locked out of the atmosphere and to provide protection against floods. But scientists and campaigners say the ban does not go far enough, is riddled with arbitrary loopholes, and will be too hard to police.

So, when the burning season kicked off last October – the first since the introduction of the new ban – Unearthed set out to find what effect the new rules were having on England’s grouse moors.

Satellite data

It is notoriously hard to track burning on grouse moors: it happens in remote locations, there is little concrete government data available, and enforcement often seems to depend on the honesty of landowners and the eyes of the public.

In recent years, a growing movement of volunteers has been working to document the fires. Hikers, fell runners and activists report details of the burns they spot to campaign groups like Wild Moors, or to the RSPB. But these reports don’t always come with precise coordinates, making them hard to attribute to particular landowners.

It is harder still to identify which burns might be in breach of the new regulations – the ban only prohibits burning on peat if it’s unlicenced, and if the peat is more than 40cm deep, and is in a site of special scientific interest (SSSI), and is protected by one of two other formal conservation regimes, and is on ground that is not too steep and rocky to mow.

There is still an enormous amount of burning going on.

So to investigate the past burning season, Unearthed developed a methodology that uses data from three satellite services – including satellites run by NASA and the European Space Agency – to find evidence of grouse moor fires. We worked with Greenpeace’s Global Mapping Hub to create a platform that overlays this evidence with government maps of England’s peat depth, conservation zones, habitats and land ownership. This was then cross-referenced against hundreds of eyewitness reports obtained by Wild Moors, a campaign group in Northern England.

The investigation revealed that widespread legal burning has continued on ecologically important English peatland since the new rules took effect, most of it on designated sites of special scientific interest (SSSIs) and other conservation areas. It also identified numerous burns in protected areas which the government’s own maps identify as deep peat, indicating potentially illegal burning in breach of the ban.

This is what we found:

- The investigation identified 251 peatland burning incidents – instances of at least one fire – between 1 October 2021 and 15 April 2022, the first burning season since the new legislation was introduced. Burns took place on moors owned by rich landowners ranging from the Queen and the emir of Dubai to software millionaires and retail tycoons.

- One in five of these burns (51 out of 251) was on land protected by multiple conservation designations, and which Natural England’s latest available map identifies as deep peat. Unearthed understands that no licenses were issued for burning on deep peat during the past season, so all of these instances warrant investigation as potential breaches of the ban.

- However, while Natural England’s database is the best official data available, it is based on modelling and does not conclusively prove the presence of deep peat. So Unearthed carried out spot checks on three moors where the map indicated potential breaches of the ban: while tests on the Emir of Dubai’s Bollihope estate found that all burning was in fact on shallow peat – and therefore legal – we found that the fire above Grimwith reservoir, on land known as Appletreewick moor, was on deep peat. Tests carried out by the BBC at Bowes moor in the Yorkshire Dales also identified burning on deep peat. Unearthed sent registered letters to the owner of the land at Appletreewick moor, and the owner of the land at Bowes moor for comment, but neither responded.

- More than 40 of the burning incidents identified in Unearthed’s analysis were on land mapped as blanket bog by Natural England’s data – the habitat the government says the legislation is most designed to protect. The fire at Appletreewick moor was one of them.

Unearthed has shared details of all the potentially illegal burns we identified with Natural England’s enforcement team; the regulator is reviewing the evidence and identifying potential sites to investigate.

‘An enormous amount of burning’

It is likely that the fires identified by Unearthed represent a small fraction of the total amount of burning over the past season. Satellites typically only capture one image a day, and they cannot see through clouds. Over the past season, campaign group Wild Moors received 1,203 reports of fires. This is an increase of 67% compared to their data from the previous season, although a rise in public awareness will likely have contributed to this. Separately, the RSPB received 272 reports.

However, campaigners and scientists said Unearthed’s findings showed there was still widespread moorland burning – including some on deep peat – and that loopholes needed to be removed from the ban to protect all peatlands and make it easier to enforce.

Dr Ben Clutterbuck, a peat specialist and senior lecturer in GIS and Remote Sensing at Nottingham Trent University, told Unearthed: “The range of observations in your findings show that there is still an enormous amount of burning going on. Your ground surveys clearly highlight where burns have occurred on deep peat. There are also large areas of essentially unprotected ‘shallow’ peatlands that are going up in smoke.”

Labour’s shadow environment minister, Alex Sobel MP, also called for the ban to be extended to all peatlands. “Peat is a hugely important carbon store for the UK and we need to preserve it, not set it on fire by accident or by design,” he told Unearthed. “The government has got an arbitrary policy that is full of loopholes, and enforcement to match. We need to prohibit the burning of peat, of any depth, in upland areas”.

The scientific consensus is that burning on all peatlands needs to stop.

A spokesperson for the Moorland Association, which represents grouse moor owners, said in response to the investigation: “We are aware of third-party reports that allege breaches of the Heather & Grass Burning Regulations (2021). We welcome Unearthed passing its information to the regulator and if, after proper assessment, Defra and/or Natural England feel it is appropriate to follow up with any of our members, they will cooperate fully and help with any queries.”

She added that: “In the meantime, our members follow best practice guidance to comply with their restoration and management plans, like checking peat depth and cutting fire breaks before undertaking management activities.”

A ‘very constrained ban’

Experts’ main criticism of the current ban is that it makes no scientific sense to continue to allow burning on vast areas of shallower peatland. The government’s own independent climate advisor, the Climate Change Committee, recommends that all rotational burning on UK peatlands is banned in order to reach net zero, and warns that burning on any depth “is highly damaging to the peat, and to the range of environmental benefits that well-functioning peat can deliver”.

Most of the fires identified by our analysis were legal, because they were set on land that has been exempted from the ban – even though the majority of them were in SSSIs and other conservation areas.

Unearthed’s investigation found that even where the ban had clearly driven landowners to change their practices, it still left scope for them to burn extensively.

On Bollihope moor in the North Pennines – owned by the billionaire Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, who is the Emir of Dubai and prime minister of the United Arab Emirates – it is clear that the estate has changed its practices since the introduction of the ban, testing the depth of the peat and mowing instead of burning in those areas that are more than 40cm deep.

Yet the moor is covered in a checkerboard of burn scars, many of which are black and fresh. It is grey, quiet and devoid of life, bar a few grouse popping out of the heather. Standing on the top of a hill, the burning here looks industrial.

Our analysis identified fires on Bollihope estate on 11 separate dates over the season. Agents acting on behalf of the estate told Unearthed that the management has been cutting instead of burning on areas of deep peat, and provided evidence that, in the areas where burns were used, the peat depth ranged from 5cm to just under 40cm.

“Your data highlights the nonsense in having this arbitrary cut off between deep and shallow peat – there is no underlying logic to the idea that there is somehow magically a difference in behaviour and carbon loss when the peat thickness changes,” Richard Lindsay, a peat specialist and head of environmental and conservation research at the University of East London, told Unearthed.

“It is a very constrained ban. Shallow peat is the most vulnerable, the most damaged and at least as extensive as the deeper peat. Also, the idea that burning should still be permitted if it is not on a protected site is utterly meaningless. The scientific consensus is that burning on all peatlands needs to stop.”

Another moor where we identified a legal fire on land mapped as shallow peat was on Goathland estate in the North York Moors, which belongs to the Duchy of Lancaster, the private estate of the Queen.

In a statement, a spokesperson for the Duchy told us that “as a responsible landowner, the Duchy continues to follow best practice in terms of sustainable land management and enhancing the biodiversity of our estates.”

I think you have pushed the scientific method forward significantly in bringing together a number of techniques

In response to our findings, the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), said that restoring England’s peatlands is a “priority” for the government and that the legislation is designed to focus on blanket bog in protected areas. Blanket bog is a rare type of peat that forms a mantle across the hills and valleys of entire landscapes because the climate is so constantly damp.

The UK is home to about 13% of this habitat globally and the government estimates that the new ban provides additional protection to 62% of the blanket bog in England.

Despite this, Unearthed’s analysis found 44 examples of burning on land identified as blanket bog by government data, including two on Walshaw and Wadsworth moor in the south Pennines. This estate has been the subject of a long-running EU court case about the legality of burning heather on peatlands. The land is registered to a company that is wholly owned, through a holding company, by Richard Bannister, a wealthy businessman and former donor to the Conservative party. Without on the ground analysis it is impossible to know definitively if the burning was in contravention of the ban. We contacted Mr Bannister’s business for comment, including detail on burning practices, but have not received a response.

‘More holes than Swiss cheese’

But critics of the ban also argue that the exemptions in the existing ban make it too difficult to enforce.

Guy Shrubsole, environmental campaigner and author of Who Owns England? said: “The government’s so-called ‘burning ban’ legislation has more holes in it than Swiss cheese – and grouse moor owners are exploiting that to the hilt.”

Luke Steele, executive director of Wild Moors, said: “By allowing grouse moor burning to continue in any capacity, the government is not only permitting peatlands to be damaged, but also giving space for the existing rules, as shortcoming as they are, to be broken. Wild Moors is urging the government to extinguish grouse moor fires once and for all by introducing a complete ban on burning peatlands.”

Soil scientist Ben Clutterbuck suggested that the complexity of the rules make them difficult to comply with for any landowner. “Peat depth can vary considerably over the scale of metres, often linked with the shape of the underlying soil or bedrock,” he told Unearthed. “It would be unreasonable to expect land managers to probe peat depth over an entire hillside, so the current legislation needs amending to include all peat soils.”

Unearthed’s investigation identified 51 fires as potentially in contravention of the ban, including the two on Bannister’s Walshaw Moor. We ran on-the-ground tests to check the peat depth at three different moors where these fires took place. These tests confirmed that on Bollihope Moor and one other estate we visited, the burning was confined to shallower peat. However, at Appletreewick we found that burning had taken place on peat that was up to 61cm deep.

A Defra spokesperson said: “Restoring England’s peatlands is a priority for the government which is why we have legislated to prevent the burning of heather and other vegetation on protected blanket bog habitats.

“We are working with stakeholders to promote sustainable management practices and plan to restore at least 35,000 hectares of peatlands in England by 2025. Natural England, supported by Defra, will investigate cases where a breach of consent or regulation is suspected according to their published compliance and enforcement policy.”

A spokesperson for the Duchy of Lancaster told Unearthed: “We will continue to work with organisations such as the GWCT, Moorland Association, Natural England and the North York Moors National Park to develop long-term strategies which will protect the beauty and integrity of this historic moorland for future generations.”

A statement issued by agents acting on behalf of the Bollihope estate said the management had used its “intimate knowledge” of the ground to ensure it did not burn on any land protected by the ban. told Unearthed that: “Arago Limited as owner of the Bollihope Estate and Starshine Management Company Limited as the entity responsible for the management are very aware of the changes in legislation over heather burning on areas of deep peat which is defined as being over 40 centimetres,” the statement read. “We have embraced cutting of vegetation [instead of burning] on these areas and have consent from Natural England to do this.”

Data processing by Anne Harris, Edikan Umoh and Olufadeke Banjo. Video production by Ali Deacon.

Over the past eight months, Unearthed has been tracking fires over the course of the first burning season since the introduction of the ban. To do this we worked with Greenpeace’s Global Mapping Hub who created a mapping platform. The map uploads daily data and imagery from three satellite providers. Satellites run by NASA use heat spot technology to identify “thermal anomalies” on the ground. We then used these hotspots to look for additional evidence of fires using satellite imagery provided by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellite and by private provider Planet. This imagery provided two types of evidence: pictures of flames and smoke from fires and before and after images of likely burn scars on the ground.

To work out if fires might be in contravention of the ban, this satellite evidence was mapped against various spatial datasets published by Natural England: for peat depth we used the peaty soils database, for blanket bog habitat we used the government’s priority habitats inventory, and for conservation zones we used databases on England’s Sites of Special Scientific Interest, Special Areas of Conservation, and Special Protection Areas. We also added the World Slope GMTED map, published by ESRI, to check land gradient.

Finally, to verify land ownership we used the Land Registry’s INSPIRE Index polygons dataset, cross-referenced against a map of grouse moor ownership published by the campaigner Guy Shrubsole. We also obtained drone footage of fires and burn scars, as well as testing peat depth on a few estates, and worked with campaign group Wild Moors who cross-referenced the 51 sites identified against their database of reports from volunteers.

Richard Lindsay, a peat specialist and head of environmental and conservation research at the University of East London, said of the methodology: “ I think you have pushed the scientific method forward significantly in bringing together a number of techniques. In terms of scientific robustness, it’s very impressive.”

Dr Ben Clutterbuck, a peat specialist and senior lecturer in GIS and Remote Sensing at Nottingham Trent University, told Unearthed: “The methodology you have developed here demonstrates that combining a range of remote sensing techniques enables the occurrence of controlled burns to be identified remotely. Land management, not just burning, can clearly be mapped and precisely dated from space.”