Carbon capture and storage: Will it ever work?

As a fractious UK general election draws near there is a remarkable consensus on one little noticed issue.

All 7 main political parties, including the Greens, think we should explore, or develop, carbon capture and storage (CCS) — albeit with varying degrees of skepticism.

It’s an enticing idea for some.

CCS refers to a range of mostly beta-stage technologies designed to capture the carbon dioxide released by burning fossil fuels and industrial processes and store it indefinitely with the intention of breaking the link between carbon emissions and climate change.

Yet in the UK and around the world CCS is at a crucial juncture following high-profile failures in Europe and the US that suggest the sector’s longstanding financial and credibility issues remain an existential threat.

The major utilities that backed Europe’s carbon capture platform have this year dropped out, citing cost concerns; and the US government has pulled the plug on its once promising FutureGen CCS facility, also due to money troubles.

Despite years of vociferous backing from the International Energy Agency (IEA), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and a host of major world leaders and most political parties in the developed world, CCS continues to move forward at only a snail’s pace — it’s lagging behind its development targets by a factor of 10.

Compared to renewables – a technology which has never achieved anything like such consensus – it’s non-existent.

Yet there’s still an appetite for CCS, and the IPCC still expects it to provide 14% of the world’s carbon emissions cuts by 2050. Without it there is a hole in the plans of global institutions to tackle climate change — but patience is waning.

Graeme Sweeney, who runs the EU’s Zero Emissions Platform (ZEP), told Unearthed: “The next seven years are critical for CCS”.

Carbon dioxide gas is captured, most often at a power or industrial station, then funnelled through pipelines to be injected (or ‘stored’) in rock formations underground.

In many ways, CCS is competing against technologies such as wind and solar power that have seen their costs plummet in recent years to the point of near price-parity with fossil fuels.

That has seen a change in what people want from the tech. A recent study from Oxford University said technology shouldn’t be used for coal power because there are viable alternatives (namely renewables).

Despite these significant obstacles, proponents argue there could still be a place for CCS even if efforts to use it for power generation fail: the industrial sector.

Especially in recent weeks, energy analysts have loudly advocated for CCS use in energy intensive industries such as steel, cement and paper, with the think tank Green Alliance saying it is “clearly the lead technology for carbon mitigation [in industry]”.

Where CCS is at around the world

According to the Global CCS Institute, the 13 carbon capture projects currently in operation around the world, along with the nine under construction, should have the capacity to capture 40 million tonnes of CO2 a year.

(Credit the Carbon Brief for the interactive map below, which features in their ‘Around the World in 22 CCS Projects’ piece)

There’s also the possibility that, like FutureGen, some of these projects will fall victim to inherent financial foibles, but there are many of possible projects just getting off the ground as well.

Among those prospective projects are the two finalists in the UK government’s CCS competition – The White Rose and Peterhead – the winner of which (or both or neither) will be decided by year’s end.

There are only two active projects on the continent – both in Norway – that together sequester around 1.5 million tonnes of carbon a year — a far cry from the 220 million the EU wants to bury by 2030.

‘Not an option for the foreseeable future’

RWE, one of the leading utilities that left ZEP in January, told Unearthed in a statement it did so because “the economic conditions and the regulatory and economic environment have changed so that CCS is not an option for the foreseeable future”.

Though the German energy giant maintains it still supports CCS, its exit demonstrates an industry-wide struggle with a technology upon which its future may depend. It’s a problem which has angered many of the technology’s advocates.

Chris Littlecott, an energy expert from think-tank E3G, told Unearthed: “The coal sector has shown itself to be spectacularly incapable of aligning different interests to invest in CCS.

“It seemed logical to policy makers that coal producers and utilities had a self-interest in advancing CCS. So far that hasn’t been the case.”

“In my experience they have been willing to talk about CCS while blocking any meaningful policy approach.”

It is a sentiment echoed by the UK’s former climate envoy John Ashton who, in a furious open letter to Shell, a company has long-championed CCS and currently runs the Peterhead project, wrote: “There is no engineering reason why dozens of large CCS installations should not already be running across Europe.

“With no compact to share additional costs between taxpayers, consumers and shareholders, CCS at scale remains empty talk.”

Stuart Haszeldine, a CCS scientist at Edinburgh University, agreed: “CCS is proceeding much much slower than any other renewable power technology.”

He told Unearthed this was down to the government policy failures, particularly the lack of a high carbon price.

He said it should be “treated more like renewables with initial subsidies”, a view shared by IEA analyst Simon Bennett who this year said there shouldn’t be “unnecessary favouritism”.

Whilst renewables receive support per unit of power generated, CCS projects have generally been offered upfront capital without ongoing subsidies.

And whilst the UK’s new Contracts for Difference (CfD) scheme could change this, per unit subsidies for CCS run into a problem which doesn’t apply to renewables or nuclear — the cost of gas or coal can change.

A recent report from the European Commission proposed binding CCS targets as another possible policy solution.

CCS with oil recovery — less expensive but less clean

Nearly three quarters of CCS projects around the world (10 in operation and 6 in construction) will send their captured carbon dioxide right back into fossil fuel extraction via Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) — and this may undo more than 60% of CCS’ climate benefits, according to a Grist analysis.

CCS with EOR simply makes more financial sense, and an actual commercial-scale project was completed late last year at the Boundary Dam coal-fired station in Canada.

Boundary Dam, which was designed to capture 90% of carbon emissions, wasn’t cheap — it cost $1.2 billion in total, and received almost $200 million in subsidies for its $280 million carbon capture.

It was, however, made more affordable than regular CCS through a partnership with Albertan oil company Cenovus, to which it sells the captured CO2.

Sask Power, which runs Boundary Dam, claims the CCS is “exceeding expectations” and Haszeldine told Unearthed the Dam’s next conversion is projected by the firm to cost 30% less.

In the US, the government has proposed that every major CCS power plant project in country sell its scrubbed CO2 to the oil extraction industry, according to a new report from Greenpeace US.

This isn’t a new thing, CO2 augmented oil recovery has been going on stateside since the 1980s and back in 2004 the sector’s demand for CO2 even outstripped supply.

Indeed the soundest financial case for CCS is EOR, because it makes little sense otherwise. Using EIA estimates, Greenpeace US found that, per unit of electricity, CCS would cost nearly 40% more per kg of avoided carbon dioxide vs solar, 125% vs wind and 260% vs geothermal.

How ‘clean’ this process is depends on whether the gas used is stored indefinitely and whether it allows access to oil reserves which may not otherwise have been burnt.

In the US, CCS may not have any climate benefit at all — it may even increase emissions overall by giving access to oil which, without the gas, would otherwise stay in the ground.

One analysis claims that up to 185% more oil per well can be extracted using CO2 injection.

CCS advocates argue that EOR using captured carbon dioxide is the lesser of a number of evils, including oil exploration in the Arctic or the development of tar sands. That’s of course assuming oil and gas companies pursue reserves that conflict with climate change targets.

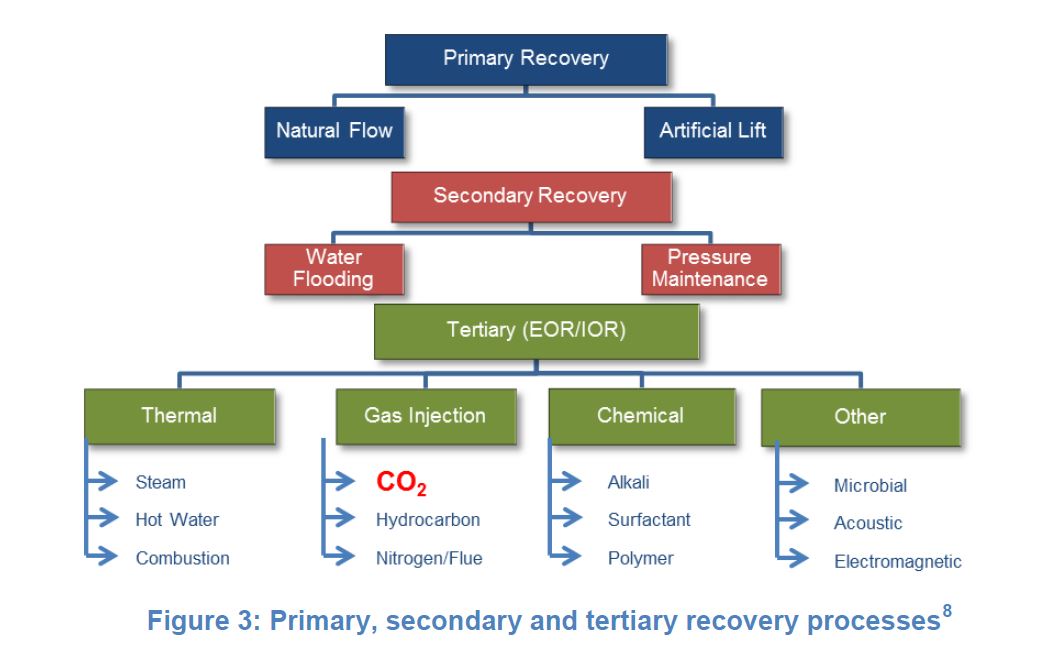

Enhanced Oil Recovery is already being done in the US, UK and other places by injecting different gases, chemicals, desalinated water, or using thermal processes or even microbes — captured CO2 is the the only one with any sort of climate co-benefit.

That’s to say nothing of the technique’s potential environmental risks and impacts. The In Salah project in Algeria, one of the few large scale CCS projects in the world, shut down indefinitely back in 2011 because the CO2 injection itself caused seismic activity that cracked the cap rock — also highlighting the challenge of storing a gas indefinitely.

And in the US, where there are already 12 million oil and gas wells, a quarter of which are abandoned, uncapped and unmonitored, and where the regulatory system is notoriously lax, what is the likelihood that CO2 will stay in the ground?

CCS on manufacturing

But whilst CCS faces competition from renewables and nuclear when it comes to generating power there is another little understood area where projects are being developed — capturing the emissions from industrial processes.

Think tank Green Alliance last month said: “It’s hard to see how some industries will decarbonise their process emissions without [CCS].”

That’s because sectors such as cement manufacture, steel making, paper-making and chemicals emit CO2 as part of the manufacturing process. Many of them also require vast amounts of heat; making it hard (and relatively inefficient) for them to run on just electricity — however clean its generation.

In a recent blog, director of non-profit the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit Richard Black said by obsessing over CCS in the power sector, the UK is “shooting at the wrong target.”

He said: “It’s like one of those diet issues when you spend years being as careful as you can with the fat, only to learn that fat is good and carbs are the real villain.”

This is a problem because – as BP found in Algeria – there is likely to be only so much viable space to store vast quantities of gas indefinitely underground so government’s need to be careful how it’s used.

E3G’s Littlecott told Unearthed: “We have limited access to CO2 storage space and need to maximise the value of CO2 stored, not the volume. And in that context, CCS on coal and lignite offers the lowest value per tonne of CO2 stored.”

“A CCS strategy that seeks to maximise social benefits would focus on CCS for industrial emissions and gas power generation”

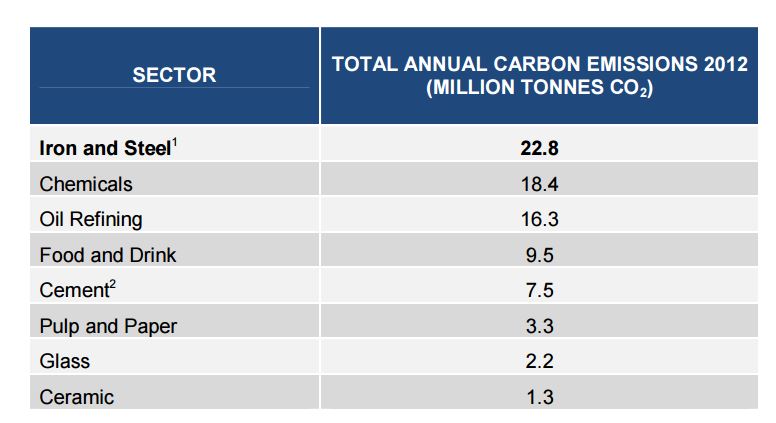

The following eight energy-intensive industries together produced more than 80 million tonnes of CO2 in 2012 — that’s 14% of the total UK emissions from that year.

According to new analysis from the UK’s Department of Business, carbon capture would enable the steel sector, for instance, to cut its carbon emissions by up to 40% more than it would without.

If CCS proves viable, it is anticipated it would make up more than 50% of the sector’s decarbonisation efforts — that’s the difference between cutting 4.5 million tonnes a year and cutting 8.6 by 2050.

It’s an aspect of CCS that ZEP chairman Sweeney was also keen to stress in an email conversation with Unearthed, adding that separating the transport and infrastructure part of CCS process from the carbon capture itself is “essential for industries to participate”.

Yet CCS for industry may also be eclipsed by other technologies. Converting renewable energy to gas is at an even earlier stage than CCS but is already underway in Germany and Denmark.

There could be a clean energy future which involves burning fossil fuels and burying the waste, but the deployment of carbon capture is anything but a done deal.