What does Amber Rudd’s speech mean for renewables?

Amber Rudd’s energy policy reset speech was a mixed bag for renewables – at least compared to the woeful expectations which preceded it.

The door was left open for offshore wind – as long as it meets unspecified new cost reduction aims – but renewables in general were hit with a possible new charge so there’s no comfort for small-scale wind and solar.

In headline terms the energy and climate secretary said that DECC expects to see 10GW of offshore wind before 2020, supporting around 14,000 jobs, on current plans.

Post 2020, she said there could be a further 10GW of offshore wind built – but only if the industry rapidly reduces its costs.

Govt will hold 3 more CFD auctions for offshore wind, but only if costs come down, says Rudd. (Presumably to £100/mwh target)

— Jess Shankleman (@JessicaBG) November 18, 2015

There’s the rub, there is still a good deal of uncertainty about what happens post 2020.

Rudd warned there will be no further subsidies for the sector if offshore wind does not reach cost-competitiveness – by which (commentators supposed) she meant that they had to hit their industry aim of £100/MWh by 2020. Though this has not been confirmed.

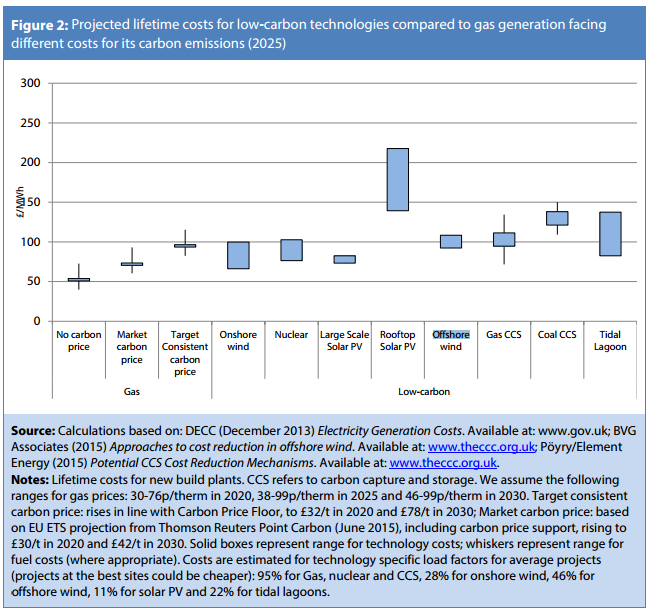

Renewable UK, which represents the offshore wind industry among others, said: “offshore wind companies are confident they will be cost competitive with new gas and new nuclear by 2025” – by which they mean they will reach £90/MWh by that time.

We really don’t know whether Rudd meant cost-competitiveness with other generation by 2020 or 2025. What she actually said was pretty vague: “The technology [offshore wind] needs to move quickly to cost-competitiveness. If that happens we could support up to 10GW of new offshore wind projects in the 2020s.”

If she meant 2020 this could cause considerable uncertainty and problems for investment into the industry.

Offshore wind costs have been coming down over the past few years. In the latest round of capacity auctions contracts have been signed at around £120/MWh, compared to costs in 2011 estimated at around £150/MWh.

The government’s advisors – the Committee on Climate Change – show it’s possible for the sector to reach around £100 per MWh by 2025 (see graph below).

How much offshore wind?

Assuming that offshore wind passes the test, and manages to maintain government support in the 2020s, is 20GW to 2030 a lot?

The CCC say that on top of the 10GW expected by 2020 we need a minimum of 10-20GW of offshore wind to be deployed between 2020 and 2030 to meet our decarbonisation goals depending on how many nuclear plants, onshore wind, solar plants, and CCS we build.

From the CCC’s report on possible scenarios to make the UK’s 5th carbon budget, it looks like in all their different scenarios they expect over 20-25 GW of offshore wind in 2030 – and we currently have 5.7GW installed or under construction – but this is a minimum, and if costs go down faster than expected it could be towards mean deployment in the 2020s doubles.

Rudd’s expectations are in line with the CCC’s minimum offshore wind deployment.

The problem is if – as planned – the government halts all new onshore wind and solar development, then this may not be enough to meet its targets for cutting emissions.

Onshore wind and solar

Which brings us to the cheapest forms of renewables. Onshore wind and solar.

Rudd said in the reset speech that support for onshore wind was being scrapped early because its costs had come down, and there was enough in the pipeline for 2020.

According to DECC, they are on track to meet their 2020 renewable electricity generation objective – but Rudd admitted in a recently leaked letter that the UK is not on track for the overall renewable energy target.

“This sums up the Government’s approach: big is beautiful, small is too complicated even if it performs better. Putting all your eggs in one basket like this is really risky” – Bridget Woodman, University of Exeter

The problem is DECC’s ‘objective’ is meaningless whereas the overall target is mandated by the EU – so more renewable generation could be used to plug the gap. And onshore wind is the cheapest renewable, already cost-competitive with gas.

As for solar, she said an extra 4 GW of solar will be in place by 2020, adding up to 12GW by that time, more than the 10GW by that point that energy minister Andrea Leadsom previously stated.

Rudd said that this was despite ‘cost controls’ on subsidies.

Charges for intermittency?

Rudd’s speech also indicates that the government is going to penalise intermittent renewables generation for its intermittency. She stated: “we also want intermittent generators to be responsible for pressures they add to system when wind doesn’t blow or sun doesn’t shine”.

It’s not clear yet what that means, but it could be some kind of a charge to renewable power producers to cover the costs of balancing supply.

The CCC said in its recent scenarios report that though “It is possible to ensure security of supply in a decarbonised system with high levels of intermittent and inflexible generation”, there are costs associated with variable output. They estimate this would represent around £10/MWh for both wind and solar for the deployment levels in its 2030 decarbonisation scenarios.

Energy experts seem to agree that making renewable generators pay for intermittency would be inefficient and expensive – even though opinion differs on whether renewables or the system as a whole should compensate for intermittency.

Robert Gross, director of Imperial’s Centre for Energy Policy and Technology, told Unearthed, however, “It’s quite right that renewables should bear the system costs they impose as penetrations rise to levels that are high enough to affect system balancing and operation. However this does not mean each individual wind or solar plant should be obliged to invest in dedicated back up. This would be inefficient and impose unnecessary costs on bill payers.”

He added that solar and wind impose system costs much larger than those imposed by nuclear, coal and gas plants going down; “We can ignore this at low penetrations as it’s lost in the noise but not at high penetrations.”

Jim Watson, director of the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC), said, however: “There is clearly a cost to intermittency… But that doesn’t mean that we should make every owner of a wind farm or solar PV installation responsible for their own balancing. That would be inefficient and costly.

“Balancing is a system problem – and should therefore be done on a system-wide basis. There is a case for ensuring that intermittent generators pay their fare share of these costs, but other generators and users of the electricity system should share those costs.”

Catherine Mitchell, professor of energy policy at University of Exeter agreed on the need for systemic change, saying “I think the point is that the system is set up for fossil and nuclear and if you really want a renewables plus energy efficiency system you would set it up in a different way and so the costs are different…but in any system you want the actual plants to pay their way – it’s just that, unless the agreement has changed, it is new nuclear that is not going to do that.”

Despite diverging views on how fair it is to make solely renewables pay for its intermittency, it is clear that if renewables have to pay in some way to cover the times they are not generating this could impose costs on solar and wind generators.

Whether this could make a difference to the viability of projects depends on how marginal they are and how much intermittent capacity there is as a proportion of power generation – the more there is the higher the costs will be cumulatively, according to the CCC.

Big vs small

In her long-awaited speech, Rudd said that the markets must decide how the UK generates its energy in the future.

She said “It is not necessarily the job of Government to choose” between large, centralised power plants – nuclear and gas, both of which the government is pushing – and decentralised community energy “supported by storage, interconnection and demand response”.

But it appears – from information in her speech – that the government is choosing. The intermittency charge to renewables on top of the subsidies bonfire could hit the sector; while large projects like nuclear and offshore wind are preferred via subsidies.

It is proposed that gas will be supported through capacity payments – which is a subsidy in all but name.

Bridget Woodman, an energy policy academic at University of Exeter said: “Singling this [offshore wind] out for support, however qualified, shows what has been expected for a while: the majority of the UK’s effort on renewables will go on large scale, centralised complex installations, rather than smaller scale technologies which are cheaper and quicker to deliver.

“This sums up the Government’s approach: big is beautiful, small is too complicated even if it performs better. Putting all your eggs in one basket like this is really risky.”

A DECC spokesperson told Unearthed: “The majority of renewable technology depends on something happening that is out of our control – the sun shining or the wind blowing. Whereas a gas or nuclear station are going to provide you energy regardless of what is happening elsewhere. Our priority is secure energy.”