Every type of new power generation in needs a subsidy

In her long-awaited ‘policy reset’ speech Energy and Climate Change Secretary Amber Rudd tried explaining all her cuts and changes to green subsidies.

In keeping with the department’s statements so far this year, she suggested subsidies for renewables were problematic because they could increase the cost of energy for consumers.

“We can only expect bill payers to support low carbon power, as long as costs are controlled.”

She even admitted that wind and solar aren’t the only types of electricity in need of subsidy, that all new build now requires at least some semblance of government financial support.

This, she claimed, is partially the result of her predecessors Eds Davey and Miliband messing with the market in a misguided attempt to cut carbon emissions.

Instead, she said, the market can find the cheapest way to ensure our energy security and cut emissions. One problem: that has never actually happened.

The economics of power plants were poor years before the UK started to go green.

It’s simply the way the energy market works: Capital costs are too high for investors to make bets on the price of power.

And scrapping green subsidies, especially since new gas and nuclear will continue to get subsidies, won’t undo any alleged market distortion.

Distorted market

“Subsidy should be temporary, not part of a permanent business model,” Rudd said as she outlined her ambition of a subsidy-free energy market by 2025.

Right now many subsidies aren’t even doing what they’re supposed to.

Trafford gas plant – the only new build recipient of last year’s capacity market subsidy – recently announced that it still can’t make its numbers add up.

It’s actually renewables – and onshore wind in particular – that have a chance of developing to the point of going ‘subsidy free’ — though they will require government backing for a few years still.

Why the quotation marks? Because the very concept of subsidy free is almost impossible to define.

Let’s just say something is subsidy free if it is economic to build and run at the the current cost of power.

Even then there needs to be some way of assuring investors that will still be the case over a number of years.

Here’s an Unearthed run-through of the major types of UK power, why they need subsidies and what kind of support they’re currently receiving.

Gas

The main thrust of Rudd’s reset speech was that the coal age is ending, and the gas age is taking off.

She announced DECC’s intention to build a new fleet of gas power plants, though the exact number hasn’t yet been confirmed.

But here’s the thing: gas is pretty consistently uneconomical.

Rudd herself even admitted: “Not even gas-fired power stations can be built without government intervention.”

Amber Rudd admits bills will rise as Britain builds fleet of new gas powered plants- "We have to build new infrastructure."

— Steve Hawkes (@steve_hawkes) November 18, 2015

And, according to Steve Hawkes from The Sun, she also indicated that consumer energy bills will rise as the government funds “new infrastructure.”

Which is, by the by, is the same reason given as to why DECC is cutting green energy subsidies.

But back to gas: It’s economic woes aren’t exactly new.

A recent Unearthed analysis found that on only a couple of brief occasions in the last 10 years has building and running a new gas power plant made financial sense — and that’s hardly enough time to instil investor confidence.

The cost of building new gas plants has outweighed the benefits of selling gas for years — even before the introduction of the Renewables Obligation (RO) subsidy.

All you have to do is look at how many gas plants have been built over the past decade versus the ‘dash for gas’ in the 1990s.

So to incentivise new gas power, the government designed something called the capacity market mechanism — which is for all intents and purposes a subsidy.

What is the capacity mechanism?

Essentially the government pays energy firms to keep their power plants on standby at times of peak demand.

National Grid says how much energy it needs to keep the lights on, and DECC ensures it has that available through capacity payments bid on in an annual auction.

This is not to be confused with National Grid’s strategic reserve which does roughly the same thing but over a shorter period of time.

It’s also essentially a subsidy.

As I mentioned earlier, despite the special 15-year contract on offer for new gas, the capacity market has so far failed on that front.

The only new power station to win a contract in last year’s inaugural auction – the 1.6GW gas-fired Trafford plant near Manchester – recently revealed it faces delays and financial woes.

Most of the money for emergency capacity went to existing gas and – gasp – coal (which we’re meant to be moving away from).

In her speech, Rudd said: “We are already consulting on how to improve the Capacity Market.”

Read our analysis on the economics of new gas plants

Solar

The cost of solar may be falling and all that (panels are down 80% since 2010), but it still needs the government to protect it from the volatility of the energy market — and will do for the foreseeable future.

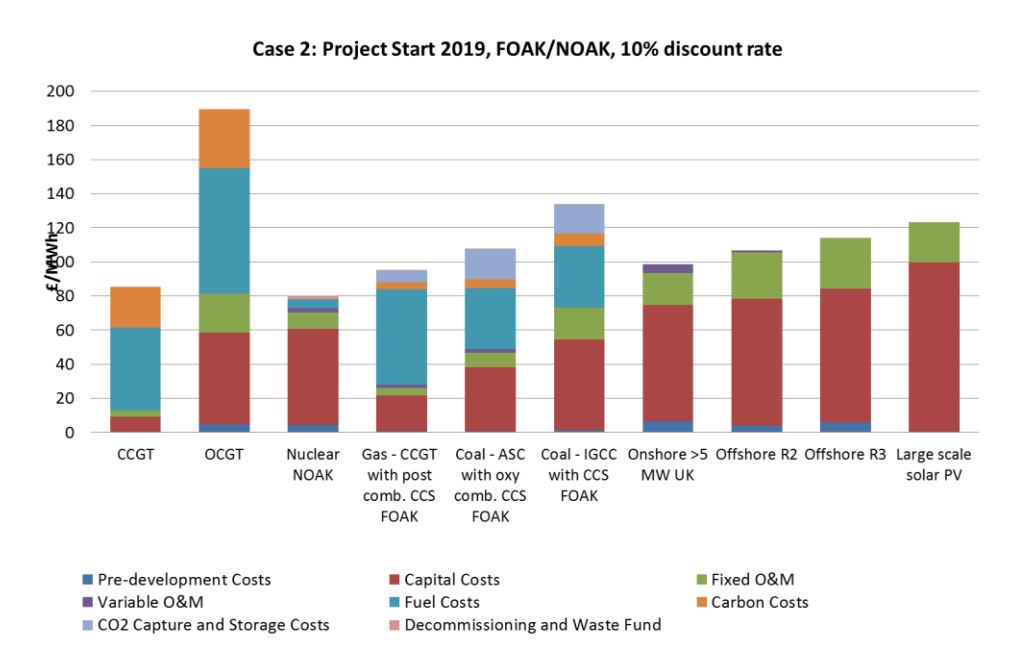

According to DECC’s 2013 Electricity Costs report, energy from large scale solar PV costs more than £150 per MW hour and will cost around £120 per MW hour in 2019.

Well the Contracts for Difference (CfD) subsidy auction earlier this year saw five large solar projects get strike prices far lower than that.

It’s thought that the two that bid in at £50 per MW hour aren’t financially feasible and won’t actually happen, but the other three have a strike price of £79 — if they make it then the falling price of PV will have dramatically outpaced government projections.

At this point nobody knows what Rudd wants to do with the CfD.

What is the Contracts for Difference?

A complex mechanism by which the government agrees to ensure generators get paid a fixed price for power they produce.

This is done by refunding or reclaiming the difference between that and the wholesale price.

It’s a good deal for the owners of, say, new nuclear power plants but don’t bother trying to get one for the solar panels on your local school.

Then there’s the Feed-in-Tariff (FiT), designed to support small scale renewables like rooftop solar and community energy projects like the solar schools.

Well the government is looking to cut that one by 87% — to the dismay of everyone from climate diplomats, international clean energy giants and mom-and-pop solar outfits from middle England.

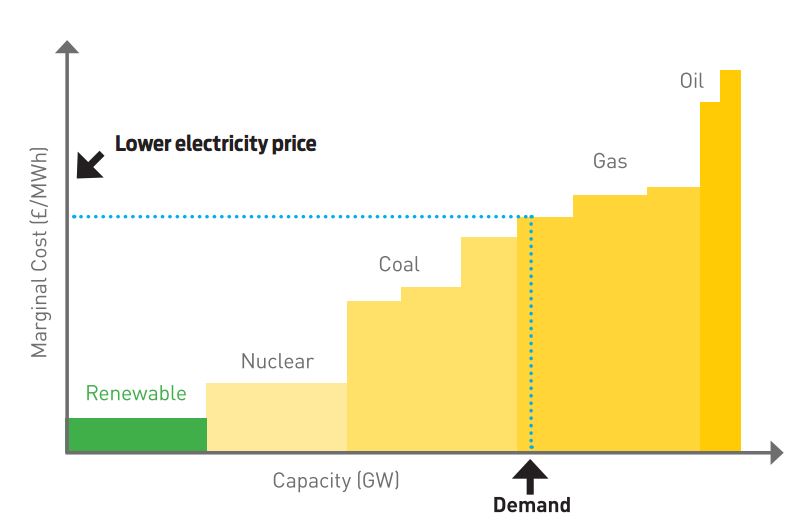

Good Energy CEO Juliet Davenport told Unearthed the other week that the cuts to the FiT are being made without appreciation for the fact that renewables bring down the wholesale cost of energy (it’s called the Merit Order Effect) — meaning the subsidy monitoring mechanism Levy Control Framework (LCF) doesn’t actually do what it was supposed to.

In her speech, Rudd said she expects the UK will go from 8GW of deployed solar today to around 12GW by 2020 — which would mean the current installation rate would slow down.

Find out the Winners and Losers of the Government’s subsidy agenda

Nuclear

Nobody is disputing new nuclear’s need for subsidy; all you have to do is look at the singular project in the pipeline to see the extent of government financial support.

The nuclear plant to be built at Hinkley Point in Somerset by French and Chinese energy companies will get £92.5 per MW hour — nearly double the current cost of power.

Across its 35-year lifetime, and including the capital costs to get the whole thing built, Hinkley has struck a deal worth £81 billion — though an Unearthed analysis has found that only half of that is actually a subsidy.

Hinkley on its own looks set to add £15 to household energy bills, and if the proposed plants at Bradwell and Sizewell go ahead then nuclear will weigh in about £33 a year for UK consumers.

Not only that but nuclear represents a pretty major spanner in the works for Rudd’s purported plan for an practically subsidy-free energy market by 2025.

Amber Rudd: we want to see a competitive electricity market with government out the way as much as possible… by 2025.

— Emily Gosden (@emilygosden) November 18, 2015

Under its CfD Hinkley will continue to be subsidised for decades, and Sizewell and Bradwell for years beyond that — and that’s assuming they even get built by that time.

So let’s say Rudd simply means that no more subsidy contracts will be awarded after 2025, well what does that mean for new nuclear?

There’s nothing to suggest the cost of nuclear will fall. It will probably continue to need subsidies.

As Professor Steve Thomas from the University of Greenwich has said: “Nuclear power has been around for more than 50 years and during that time, real costs have consistently gone up.

“This is despite the nuclear industry claiming for decades the cost curve for nuclear would start to go down as past problems were solved by the latest generation of nuclear designs.”

Q&A: What’s going on with Hinkley?

Wind (Onshore and Offshore)

The Conservative Party have pledged to ‘halt the spread of onshore windfarms’ because, well, some of their constituents in the countryside don’t much like the look of them.

According to this year’s CfD auction, onshore wind power has an average cost of around £82 per MW hour — already cheaper than Hinkley and still falling fast.

A recent report from the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) says onshore wind (and solar, in fact) will essentially be ‘subsidy free’ by the end of the decade if you consider the full cost of carbon.

That followed a study by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) that claims wind is already competitive with fossils if you take into account network, health and carbon costs.

A recent Policy Exchange blog by Richard Howard does a job explores the possibilities, complexities and implications of this whole thing.

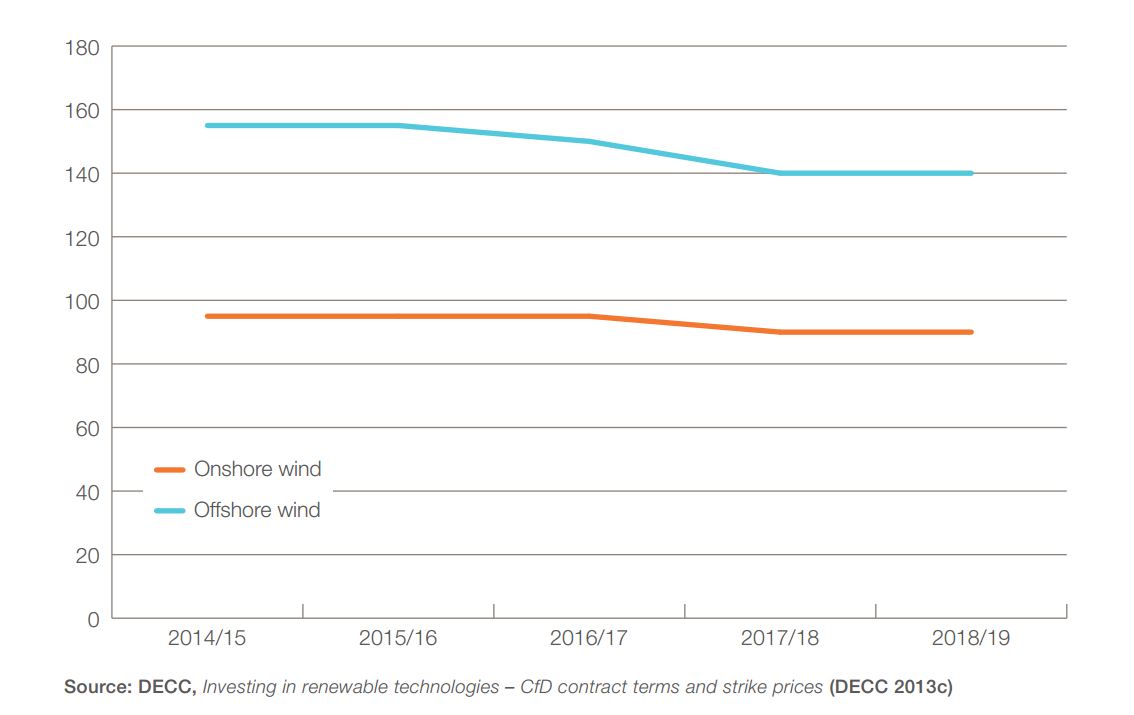

Offshore wind, on the other hand, remains the most expensive form of generation that is, y’know, actually happening.

At £117 per MW hour it is still massively subsidised under the CfD, but it’s worth noting that offshore wind got £38 cheaper in just three years — and is ahead of schedule to meet the government’s target of £100 per MW hour by 2020.

At this point we’re not really sure where the government stands on offshore wind.

Rudd called it the “one area where the UK can help make a lasting technological contribution” but she also said it is still “too expensive”.

Coal

It’s not even on the table without carbon capture and storage (CCS) as per this government’s phaseout commitment, but even cheap ol’ coal is too expensive without subsidy.

Ignoring that the winner of the UK’s CCS competition is in line for £1 billion in government money, coal is just too bloody expensive to build — especially with a carbon price.

Read Amber Rudd’s speech in full

So there you have it. Renewables aren’t the only type of energy that needs subsidy. They all do.

This piece was updated after Amber Rudd delivered her speech