Five cool trends in green housing

With a third of UK carbon dioxide emissions coming from housing, creating more sustainable homes is a crucial part of meeting the UK target of an 80% cut in CO2 emissions by 2050. Not that the Conservative government seems to recognise that. It has scrapped both the Green Deal, which supported homeowners in making emissions-busting home improvements, and the Zero Carbon Homes Plan, which mandated that from 2016 all new dwellings should produce as much energy through onsite renewables as they use. The UK finance minister also just downgraded the energy efficiency scheme.

Read more:

Factcheck: What just happened to the UK’s energy efficiency scheme?

What can world leaders learn from local governments in the run up to the climate talks?

Batteries — why you should believe the hype

Despite the government’s breathtaking shortsightedness, sustainability remains a hot trend in the architecture and design world. And over half of building firms surveyed globally said they are committed to incorporating sustainability into their work. Research suggests that people living in green homes are happier and healthier, with respiratory illnesses like asthma particularly reduced – proving that sustainable building design has benefits beyond caring for the environment.

Here are five trends in green housing around the world that have benefits for both people and planet:

1. Green roofs

Rooftops covered in grass or even wildflowers and herbs seem to be cropping up (excuse the pun) all over the place. Many of them are on commercial or public buildings but green roofs can equally be planted on houses both new and old. They rarely need planning permission and have the dual advantage of both reducing emissions – by keeping homes cool in hot summers – and helping us adapt to changing weather by retaining water in heavy downpours. Plus they can be little havens of biodiversity in urban areas, supporting populations of insects and spiders.

2. Tiny houses

The tiny house movement is big in the United States and beginning to gain some popularity over here. Tiny homes can be any small dwelling but are usually wooden structures, often kooky in design, that can be easily transported on wheels. Motivated by both sustainability and cost, tiny house dwellers often profess new found happiness from decluttering their lives and downsizing their homes. With the housing crisis meaning many people aren’t able to get on the property ladder, owning a tiny home is an attractive alternative. Proponents of the tiny life – who get together for jamborees in the US – claim that people who live in tiny houses have greater financial security, often owning their home outright and having more savings in the bank than regular Joes. Living in a small space – with lower energy use and less stuff – makes tiny houses an obvious green choice.

3. Homes as power stations

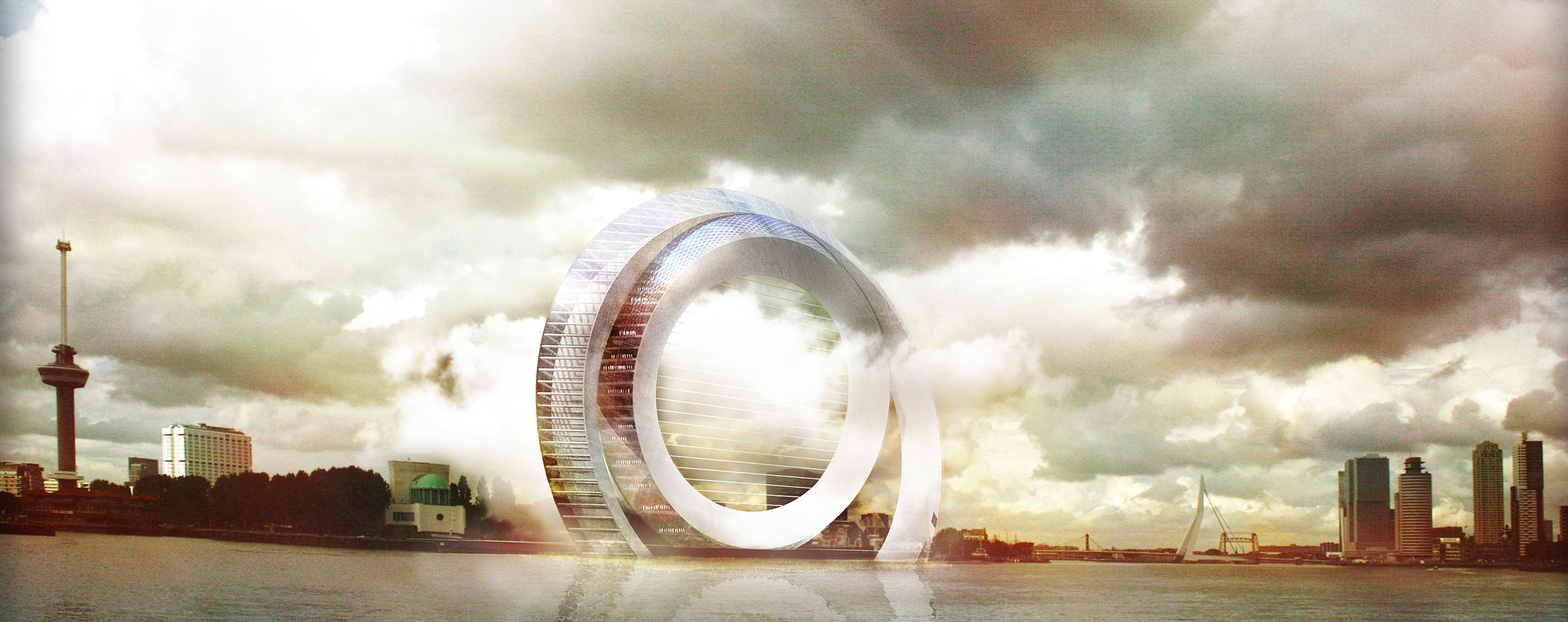

The availability of small-scale renewables for housing isn’t new but the rapidly decreasing cost of solar is making the installation of solar panels an option for more people. In the last five years the price of solar panels has dropped by 80%. Plus innovations in design and aesthetics means solar is now more attractive. Panels are available which look more like standard roof tiles or which allow natural sunlight through – like those used in Solcer House, an example of a low-cost, carbon positive home. Of course other renewables like wind or hydro (if you happen to have a stream running through your garden) can also be used to power your home. And in the Netherlands, the home/power station idea is being taken to the limits with the building of the Dutch Windwheel – a futuristic 175m generator which doubles as an apartment block and a roller coaster! What’s not to like?

4. Co-housing

Living communally and sharing resources makes good environmental sense. But we all like our own space, right? Co-housing offers the best of both worlds by providing private dwellings organised around some communal areas – such as meeting places, work spaces and gardens. Currently there are 18 co-housing projects in the UK – like Laughton Lodge in Sussex – but 60 more are in development. Residents are expected to participate in the management of the project and work together on maintenance and other tasks. Some co-housing projects incorporate small scale renewables and reduce emissions further by sharing transport and growing some of their own food. Co-housing has social benefits too, especially in combatting loneliness. In the UK, 50% of us don’t know our neighbours and a third of us live alone – a factor which can increase the risk of depression in work-age people by 80%.

5. Passive design

As well as incorporating renewables into new homes, emissions can be reduced by decreasing the amount of energy needed in the first place. Passive design refers to architectural approaches which decrease the need for energy for cooling and heating, such as clever siting, shading, ventilation and insulation. In hot climates, where living in constantly air conditioned spaces can be fairly unpleasant, passive design is especially gaining popularity – like this design for an apartment building in the Philippines which uses indoor patios every three floors to keep the building naturally cool.