Comment: The UK can ditch Hinkley and save £1bn

This is an edited version of an article published by the ECIU

As new Prime Minister Theresa May prepares to deliver the years-in-the-making final decision on the proposed nuclear power plant Hinkley Point C, there remains a number of possible stumbling blocks for the controversial project.

There’s potential legal cases in France, EDF’s parlous financial situation, Hinkley’s unpopularity with French unions in an election year, and the evidently formidable challenges of building a European Pressurised Reactor (EPR).

So, while Mrs May can conclude that “Brexit means Brexit”, it is not clear if “Hinkley means Hinkley”.

So let’s look and assess what could be done instead.

Read more

Warnings over ‘revolving door’ between EDF and UK government

Even offshore wind is cheaper than HInkley

District heating is a viable alternative to Hinkley

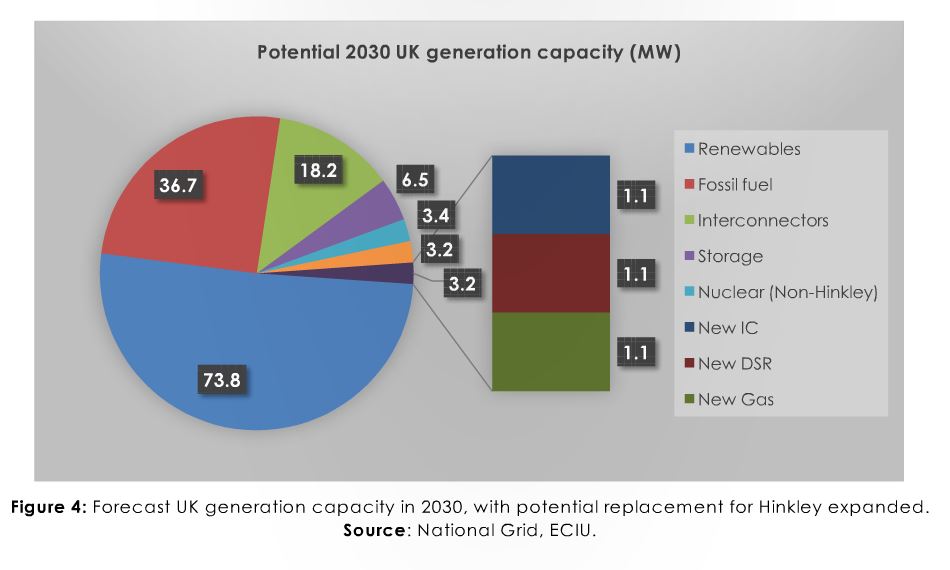

Get smart

The heads of the UK and Chinese National Grids have suggested the era of baseload is coming to an end, to be replaced by flexible systems in which ever-cheaper renewable generation is balanced by demand-side response, interconnection, storage and rapidly-responding gas-fired units.

The National Infrastructure Commission and trade association EnergyUK have both said the UK should adopt a ‘smart’ flexible system.

This raises a separate question of whether Hinkley C would usher in a new era of white-hot technology, or perpetuate the age of the dinosaurs.

The cost of doing business

Then there’s that contentious strike-price.

The contract the government is proposing to sign guarantees EDF £92.50 per megawatt-hour — and that’s in 2012 money.

It incentivises EDF to run the power station as much as possible, even if the wholesale price falls below zero.

This means, the ECIU calculates, that UK customers will pay a total of £2.5bn per year to EDF. If the cost were borne by householders, this would represent £92 per year on the average bill.

Alternatives

A new report shows that Hinkley is not essential for solving the trilemma (security of supply, decarbonisation and cost).

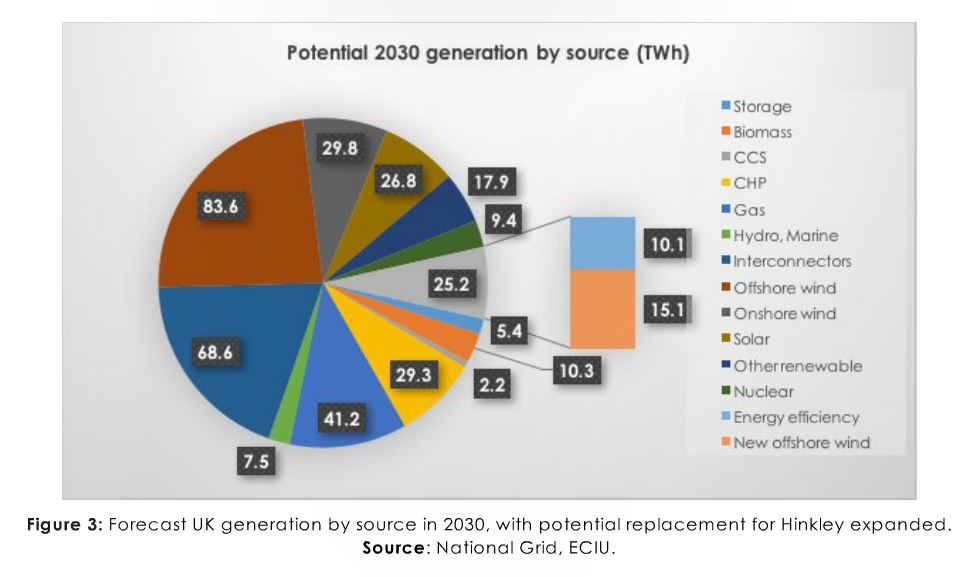

The power generated could be easily replaced by building four big offshore wind farms or three new interconnecting cables, or a mixture of the two.

Increasing energy efficiency – the lowest of low hanging fruit in terms of managing the power sector – could negate at least two-fifths of Hinkley’s output, while currently underutilised technologies like demand side response could shave gigawatts off the ‘firm’ capacity needed to match demand on even the coldest winter evening.

Compared to the eye-watering figures involved in building Hinkley, all the alternatives identified could save the UK money.

Hinkley will pump out around 25.2TWh of electricity per year: generating this power from wind farms could cut the average household bill by £10-20 per year, while replacing the capacity with peaking gas plants – which would only need to run when demand spikes – could save £16 billion in infrastructure costs.

A large number of new plants, interconnectors and other infrastructure will be built anyway, as old equipment reaches the end of its lifetime.

Hinkley will form only a small amount of this capacity. The lights will stay on

The lights will stay on

Instead of EDF’s ‘white elephant’, a proposed scenario containing a sensible mixture of the alternatives could save the UK around £1billion per year, in addition to avoiding the 35-year contract currently on the table that could lock the power sector into an increasingly outdated model of large, centralised generators and passive consumers.

It’s also worth noting that today’s ECIU report is highly conservative, considering only mature technologies rather than placing hope on those just entering the market or yet to be commercialised.

Critics of Hinkley have backed technologies such as storage, tidal power and small modular reactors which, although highly promising, are untested on the utility scale.

Considering the pace of change in the energy sector – wind and solar costs tumbling, the emergence of as-yet unknown technology and changes resulting from developments in the political landscape – it is entirely possible that replacing Hinkley could be even cheaper and easier than expected.

And if it fails to materialise entirely? Don’t worry. The lights will stay on, decarbonisation will continue and bills will fall.

Dr Jonathan Marshall is an energy analyst for the ECIU