How the UK imports coal from Russian megamines that are displacing indigenous groups

Campaigners claim the expansion of open cast coal mining in the Russian region of Kuzbass is driving locals from their homes, including the Shor people

The UK is importing millions of tonnes of coal from mines in Russia alleged to have poor environmental standards, according to official data and research from campaign groups seen by Unearthed.

The research has led to concerns that coal mining associated with environmental destruction is providing fuel to provide power for homes across the country.

As the government lays out its plan to phase out coal power in the coming years, official data shows the the UK imported over 9 million tonnes of coal from Russia in 2015, more than it sourced from any other country and – for the first time – even more than it mined domestically (8.6m).

Early 2016 data, however, indicates that Colombia is set to overtake Russia as the UK’s number one supplier.

When contacted by Unearthed most UK power companies refused to deny sourcing coal from a region in Russia where campaigners claim the industry has devastated local and indigenous communities, as well as failing to abide by the country’s environmental standards.

Refusal to disclose

With the notable exception of Drax – which also burns biomass – no UK coal power company would confirm or deny to Unearthed whether they burn coal that originates from Russia’s chief exporting region Kuzbass.

Drax admitted that it sources coal from Russia, including Kuzbass. It explained: “The sulphur content of UK coal is relatively high compared to much of the coal traded around the world so Drax looked to lower sulphur coal from the international market.”

In fact the UK government even lobbied against EU coal pollution rules, citing its excessively sulphuric domestic coal, Unearthed revealed last year.

nPower, which runs the Aberthaw coal power station, said it sources some coal from Russia, but would not go into any further detail.

EDF, EPH, SSE and Uniper refused to comment.

Read Coal Action Network’s Ditch Coal report for more info

Polluted air, contaminated water

“In the Kuzbass region of Russia the coal industry’s impacts are felt everywhere,” according to Vladimir Slivyak, an environmental campaigner with the Russia-based group Ecodefense.

As one of the few environmental NGOs operating in Russia, and with a particular foothold in the more remote eastern regions, Ecodefense is the leading group on the impacts of the country’s coal mining industry.

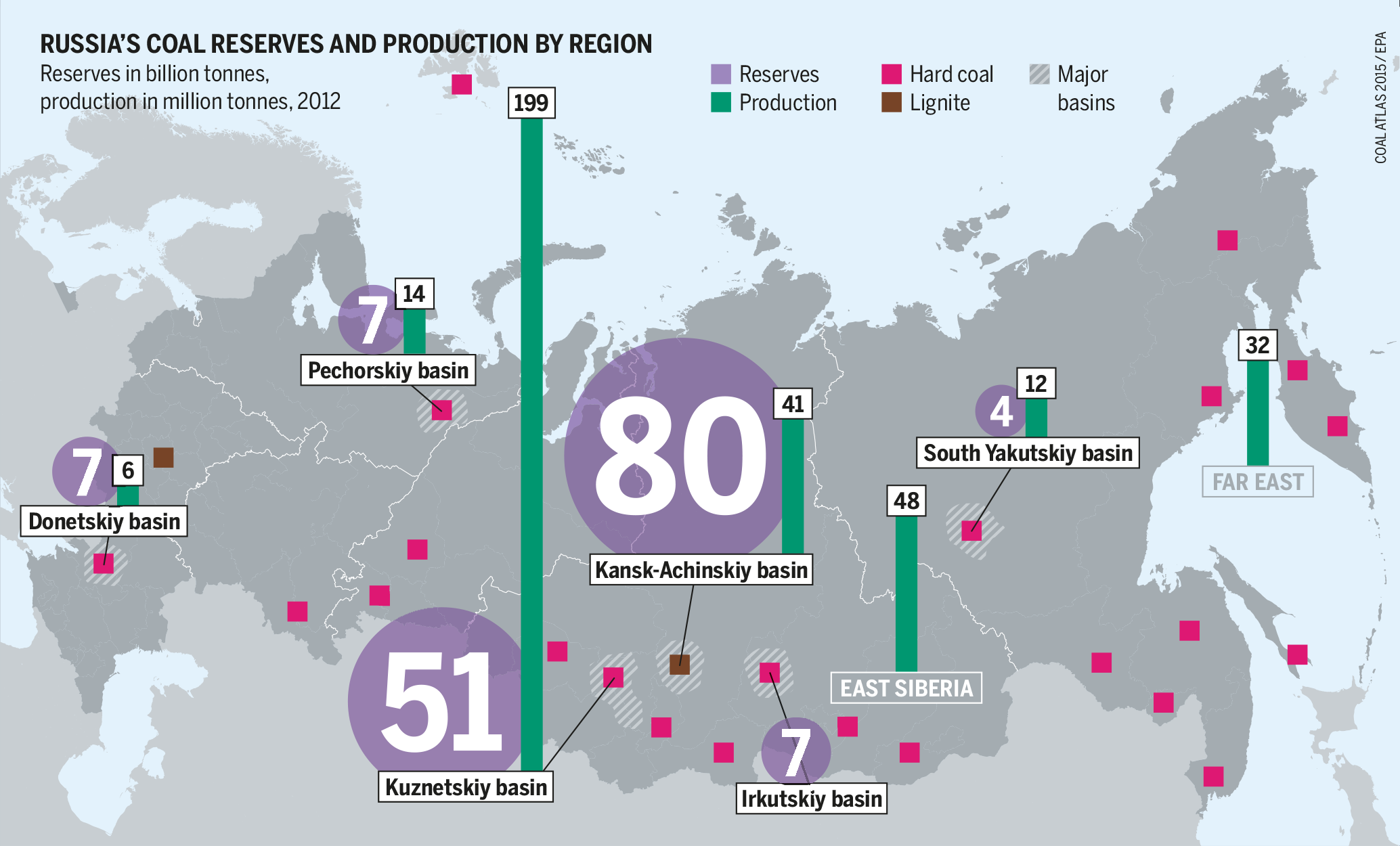

Kuzbass, which produces more 6 times as much coal as any other part of the country, is full of huge – and growing – opencast mines.

“They have expanded to the point that they are now really close to the places where people live,” Slivyak said.

“Blasting the bedrock to get at the coal sends plumes of dust into the air, it combines with the dust which blows off the unrestored heaps of mining waste and it gets in the rivers.

“Where once there were clean streams, places where people went to fish, wash and drink, there is now only lifeless water visibly contaminated by coal mining.

“Growing food in the villages beside the mines is hard, as dust covers the crops and the animals traditionally hunted have become scarce as the land has lost the ability to support life.”

Last year Ecodefense released a report on The Cost of Coal and a short documentary called Condemned.

Growth of an industry

In the 1990s the Russian coal industry underwent a radical transformation, as the country became the world’s third largest exporter of coal, after Australia and Indonesia.

But economic growth came a cost, both to the environment and the communities where the industry set up shop.

Vladimir Milov, one-time Deputy Energy Minister, was interviewed by Ecodefense on the topic, referring his home region of Kuzbass and its Governor Aman Tuleev as “deeply dependent on the industry”.

“The government,” he said, “is not performing its basic regulatory duty to ensure that private companies comply with environmental law and provide acceptable living conditions.

“Nobody wants to deal with the severe consequences of the massive rise of the coal mining industry.”

The impacts may go even further than that. Campaigners claim an indigenous peoples called the Shor are also suffering.

Indigenous peoples affected

Where there were 16,000 Shors living in the region in the 1990s, there is now just between 4,500 and 5000 people here, according locals interviewed for the Ecodefence documentary.

Where there were 9 villages, the documentary reports,, there is now just one: Chuvashka.

That village is surrounded by four open cast coal mines, overhears daily explosions and endures with toxic water.

“No-one is restoring this land,” said Valentina Borskina, a resident of the village. And so many leave.

Anne Harris, a campaigner with Coal Action Network, which recently released a report on this topic, said: “Coal mining in the Russian Kuzbass is preventing the indigenous Shor and Teleut peoples from living according to their traditions and in harmony with the land.

“The ever expanding mines encroach on their territories, covering their food growing areas with dust, polluting the water and displacing entire villages.”

Coal phaseout

Meanwhile the UK, the largest customer of Russian coal in Europe, is planning to close its remaining coal power stations by the 2025.

The consultation launched earlier this month was more than a year in-the-making, following government’s announcement in November 2015.

Coal power has seen a sharp decline in the last couple of years, as emissions regulations have bitten and cheap alternatives such as renewables have become increasingly viable.

Electricity from coal is expected to fall by 66% in 2016 alone.

Harris said the suffering caused the mining industry in places like Russia stresses the urgency of the phaseout.

“We need to open our eyes to the damage caused by coal mining, wherever it happens, and take full responsibility by closing the UK’s remaining coal-fired power stations as fast as possible,” she said.

Read more: Why the UK’s coal phaseout is a big deal

Drax comment

Out of respect to the people at Drax, who engaged with this story when other UK power companies would not, here is their statement in full:

“Over recent years Drax has significantly reduced its reliance coal – from 2010 it has reduced its coal consumption by 40 per cent. This is through upgrades to almost half of the power station in order to produce renewable electricity from compressed wood pellets. Drax’s output is now 70 per cent renewable and carbon savings of over 80 per cent are being achieved compared to coal.

The coal sourcing strategy for Drax’s remaining coal units is compliant with environmental standards, legislation and good business ethics. Coal is sourced from Russia – including from time to time from the Kuzbass region, Colombia, US and UK.

In order to comply with environmental legislation to limit emissions from coal (including the Industrial Emissions Directive) not only did Drax implement work onsite at the power station to help control sulphur dioxide (SO2) and nitrogen oxides (NOx) but it also looked at the qualities of coal being used.

The sulphur content of UK coal is relatively high compared to much of the coal traded around the world so Drax looked to lower sulphur coal from the international market.

Drax wants to continue moving away from coal and with the right support the remaining units could be upgraded to run on compressed wood pellets, enabling a 100% renewable output.”

Read more: Are biofuels really renewable?