Why sky-high coking coal prices could actually be terrible news for the coal industry

The financial press has been calling coal, and particularly coking coal, the “hottest commodity of the year” — and for short-term traders, it certainly has been.

Prices have quadrupled from the low reached at the start of the year, driven by a perfect storm of China’s strict output quotas, red-hot real estate bubble and speculative buying in the futures market.

While a price spike should be a boon for coal miners’ profits in the short term, the industry is instead turning it into a potential financial shipwreck, rushing to lock in more port capacity for coking coal. Traders like Glencore have plans to restart old mines and cash in on the latest trading craze.

Once again, we see coal infrastructure planning that looks not at the fundamentals of the market, rather irresponsibly following market spikes (just like the thermal coal boom in 2009).

New research

Just today, a Chinese coal industry think tank released a study that outlined why the recent price spike won’t last.

According to the Coal Strategy Planning Research Institute, the high price of coal (both coking and thermal) has been largely caused by shrinking domestic supply driven by government policies designed to tackle the industry’s overcapacity crisis.

Wu Lixin, who wrote the study, said: “A supply gap created by specific policies, rather than an increase in demand, is the reason for the recent price increase.”

It won’t last

High coking coal prices, driven by Chinese demand, are not a sign of improved outlook — on the contrary, they are a sign of delayed adjustment to economic realities.

Coking coal is used solely to make steel, and China’s steel demand is dominated by construction, more than half of the total, and by manufacturing of machinery, up to a quarter of total. Consumer-driven manufacturing – autos and appliances – uses just 10%. Even more than thermal coal, coking coal is a fuel of China’s old economy.

And that old economy is on its way down.

Since the global financial crisis, China has used excessive investment in real estate, factories and infrastructure to drive economic growth, accumulating mind-boggling levels of overcapacity in industry, coal-fired power plants and mining, as well as building real estate and infrastructure far ahead of demand. Construction volumes and industrial capacity additions need to come down in the coming years significantly to bring debt under control.

Exports provide limited relief. China makes up half of global steel demand — for comparison, India and Southeast Asia use 5% each. China has been increasing steel exports to alleviate domestic overcapacity, but the current export levels are clearly already unsustainable, leading to trade disputes with most major trading partners.

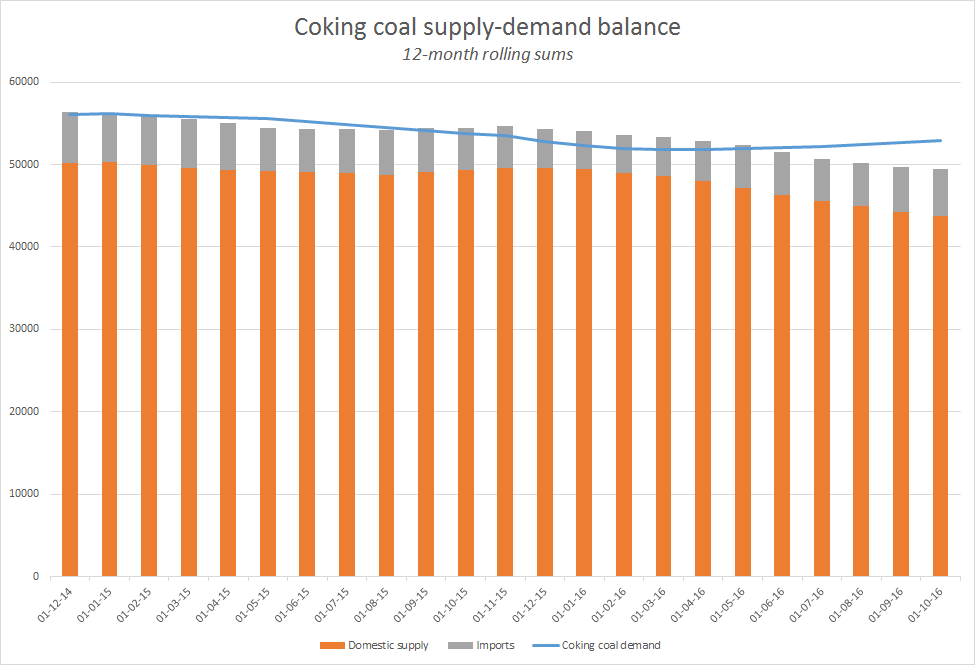

So the story for coking coal, more than just about any commodity, should be straightforward: as China’s economy shifts from reliance on government-driven construction projects and heavy bulk industry to advanced manufacturing and services, coking coal demand will fall dramatically. Indeed, that’s what took place in 2015, with coking coal demand falling 13% on year, and prices tanking.

China stimulus

What has happened in 2016 is that the government launched an enormous credit stimulus, spurring a wave of real estate and infrastructure construction, driving up demand for steel and coke. Coking coal demand was still anemic in January-February but, since April, demand is up 4% on year.

Simultaneously, another government department was responding to the rock-bottom coal prices and falling demand seen earlier. They set strict quotas for coal output, covering both thermal and coking coal, leading to a 14% fall in coking coal output in January-October 2016. The price run-ups have been inflated further by the vast amount of speculative asset buying, known as the “giant ball of money” created by easy credit.

The prices have stayed high because the government was atypically slow to respond to this apparent failure of top-down planning.

One possible reason for their lateness is that while coal prices were inflating, the government was engaged in tough negotiations with steel producing provinces and companies about eliminating 80 million tonnes of steel overcapacity, and coking coal supply ended up as a bargaining chip in these negotiations. Soon after the announcement that capacity elimination targets for the year had been met, the government relented on coking coal output quotas. Last week, a the largest state-owned coking coal producer signed long-term supply contracts with key steel companies.

What next?

2016 is an outlier for China’s economic trajectory, due to absolutely unprecedented debt stimulus.

Yet, even this attempt to supercharge the old economy alone would not have produced anything like the violent surge in imports and coal prices that we’ve seen this year: coking coal demand is still down 10% from 2014 level, and imports are at 2014 level.

What does this mean going forward?

First, the construction surge this year has made the oversupply of real estate and infrastructure even worse, making the upcoming adjustment in construction volumes even deeper. Second, the government has taken on an enormous amount of additional debt.

This reduces the scope for further stimulus and speaks to the necessity of scaling back debt-fueled construction activity in the coming years. Lastly, there is a lot of underutilized domestic coking coal production capacity that could meet more of the demand even at current levels, and as coking coal demand falls, imports are likely to get hammered.

With credit rating agencies like Moody’s singling out coal infrastructure as one of the three highest risk for credit, the writing is on the wall.