The UK government cannot stop Green Investment Bank from funding fracking after sale

Documents reveal the limitations of the government's so-called 'special share'

The British government’s decision to sell the Green Investment Bank has come under fresh criticism as newly released documents appear to undermine its ability to protect the project’s ‘green purposes’ post-privatisation.

The documents – obtained by Unearthed via Freedom of Information – describe the powers held by the ‘special share’ set up by government: It can stop changes from being made to the Bank’s official green purposes, but has limited abilities to enforce those same purposes, with no power to veto investments before they are made.

This has sparked questions over whether the Bank may find itself invested in fossil fuel projects that could be argued to reduce emissions and/or improve efficiency.

Shale gas and ‘clean’ coal are, for instance, less carbon intensive and more efficient than the old coal plants still powering the UK.

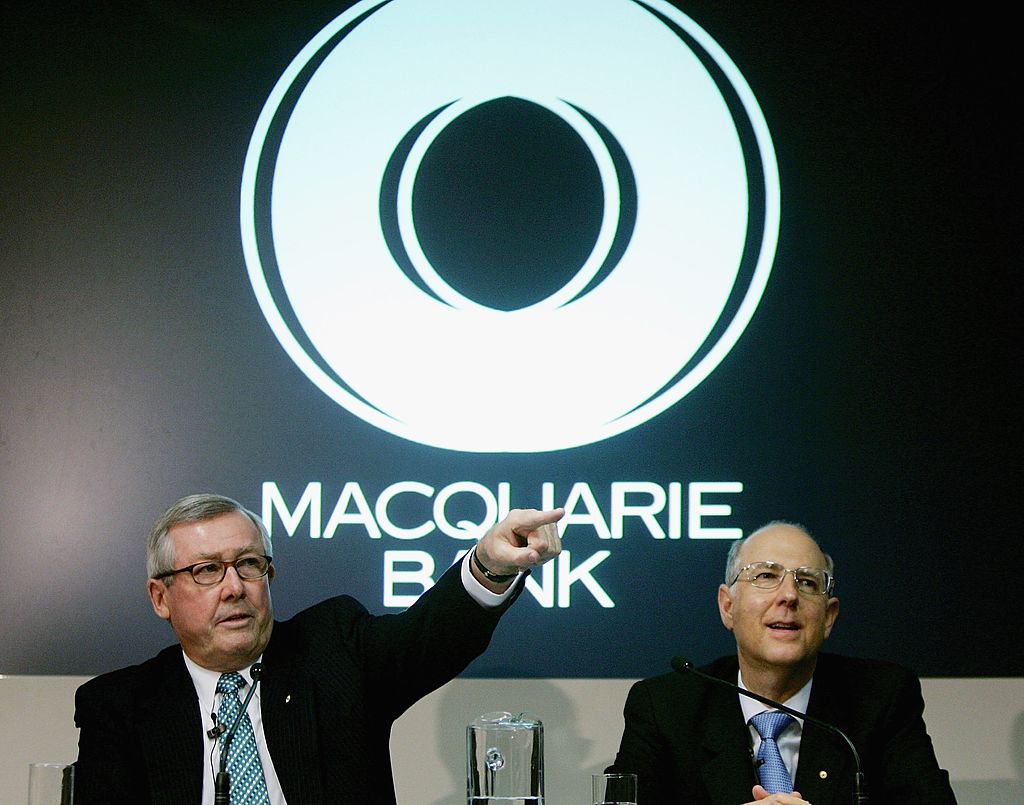

Likely buyer Macquarie is a major investor in UK fracking firms, gas power plants and the gas grid.

The Green Investment Bank refused to comment.

Read: Is Macquarie preparing to asset-strip the Green Investment Bank?

‘Botched deal’

The documents reveal that the ‘special share’ cannot intervene to stop investments before they are made.

Instead, the shareholder – a company run by a board of five independent trustees with faultless green credentials – can file what is called a ‘derivative action’ against the directors for breaching the Bank’s stated purpose.

This kind of action is the right of any shareholder under UK law, but legal experts have questioned how effective it could be in this case.

Derivative actions are often difficult, rarely successful and would depend on a court’s interpretation of the Bank’s green purposes, which are vaguely worded.

In order to protect the green mission of the Green Investment Bank after it has been privatised, the government created a ‘special share’ to be held by called the Green Purposes Company.

The company is run by five independent trustees.

Our investigation reveals that the special share has the ability to block changes made to the green purposes detailed in the Bank’s founding documents, but little power to enforce those purposes.

In a statement, Leader of the Green Party Caroline Lucas – who is running a campaign to ‘Save the GIB’ – said: “We’ve known for a while that the special share provides no guarantee that the green purposes of the bank will be retained once it is sold, but these revelations make clear that even the narrow powers available to the special share trustees are difficult to implement in practice.

“It couldn’t be any clearer: this is a botched deal.”

Special?

The documents, which came from the GIB but not from its legal team, in response to Freedom of Information request from Unearthed, outline the powers of the ‘special share’ as understood by the those inside the Bank.

They explain that the special shareholder must provide written consent for any changes to be made to the green purposes in the Bank’s constitution.

Beyond that, however, the powers of the special share appear limited.

Read the documents here

If the Green Investment Bank makes an investment that goes against its green purposes the special shareholder can file a ‘derivative action,’ a statutory form of redress that is rarely used in this way.

David Cooke, a lawyer at ClientEarth, told Unearthed it would be concerning “if the government intends to rely on a derivative action to enforce the green purposes.”

There are, he said, “significant procedural bars” that would make a successful derivative action very difficult indeed.

These bars mean “very few derivative actions actually end up before the courts”.

Not only is the derivative action process complex and cumbersome, but it doesn’t seem fit for this purpose, he said.

“We do not see that the special shareholder seeking to enforce the green purpose through the derivative claim procedure – perhaps acting on its own and acting against the rest of the shareholder base – sits comfortably with the court’s current approach to derivative claims.”

Loophole?

The documents suggest any chance of success will depend on the wording of the green purposes themselves — which leave room for interpretation and could allow for investments in certain fossil fuels.

According to the Articles of Association, the GIB is supposed to contribute to the following aims:

1. The reduction of greenhouse gases

2. The advancement of efficiency in the use of natural resources

3. The protection of enhancement of the natural environment

4. The protection of enhancement of biodiversity

5. The promotion of sustainability

Investments need only meet one of these requirements, allowing seemingly significant scope for interpretation.

Further literature provided by the Green Investment Bank (though without any legal authority) fleshes out those purposes slightly — whilst creating greater uncertainty.

In one document on the GIB’s website, entitled ‘Our Green Investment Principles’, the bank “recognises that some projects will have a greater impact than others. Progress to a lower carbon economy will not be direct or linear, but is likely to involve a number of incremental steps that, taken together, will contribute to fulfilling our larger mission”.

The wording – which mirrors some government language on shale gas – suggests that it could be argued that the GIB is able to invest in projects with questionable environmental benefits.

In fact, the GIB has controversially been a big backer of biomass in the UK, which co-fires with coal at Drax power station, produces sizeable carbon emissions itself, and sometimes comes from felled forests.

Read the GIB’s Articles of Association

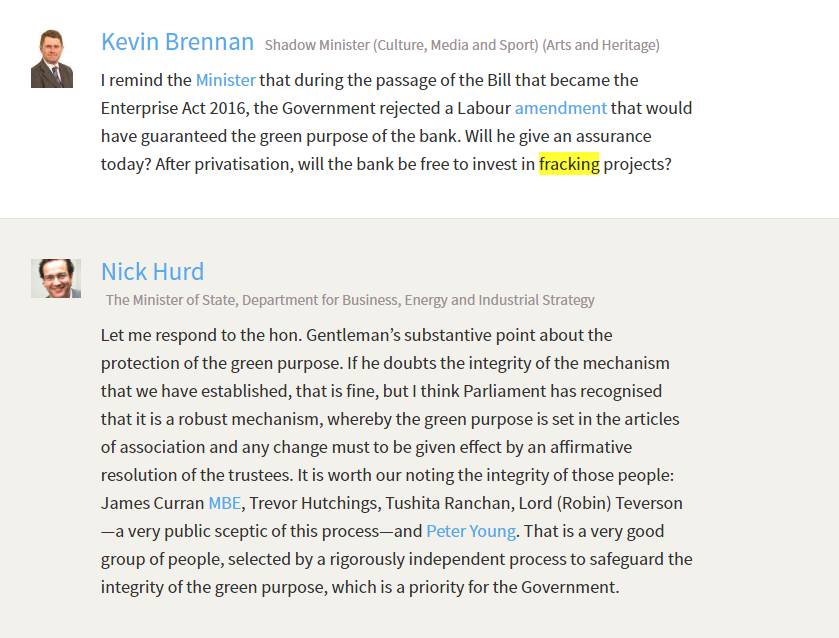

At a parliamentary debate last month, energy minister Nick Hurd twice demurred when asked point-blank by MPs if the GIB could be used to fund fracking.

In both cases, he said the ‘special share’ would protect the Bank’s green purposes.

A report from 2012 raised concerns that the Bank’s 2nd green purpose – efficient use of natural resources – could be used to justify investment in high-efficiency gas power projects.

Jonathan Church, another lawyer with ClientEarth, added: “It’s worth remembering that the Bank’s Articles have always been this generously defined and a sale wouldn’t change that.

“What will change is that you may have shareholders who are not themselves committed to a ‘properly green’ interpretation of those Articles. And this then comes back to the enforcement point.”

Likely buyer Macquarie is a major stakeholder in UK fracking firms, gas power plants and the gas grid.

And it’s in that context that the ‘special share’ would have to challenge possible violations of the green purposes.

Read about Macquarie’s fossil fuel investments

Asset stripping?

Last month an Unearthed/E3G investigation revealed that the Green Investment Bank created 10 new companies in just 9 days at the end of last year ahead of its expected sale to Australian investment firm Macquarie.

This – coupled with reports from the Sunday Times – sparked concerns that Macquarie was getting ready to asset-strip the GIB, earning up to 30% profit on its offshore wind and biomass assets.

The resulting political storm, which triggered two parliamentary debates, an inquiry from the Environmental Audit Committee, and a series of stories in influential newspapers the Mail and Telegraph, put the deal in doubt.

But reports from the Australian press this weekend suggest the UK government is set to approve the sale nonetheless.