Factcheck: Is Europe getting off coal?

Last week EU energy industry group Eurelectric released what seems on the surface to be a seismic announcement.

With just a few exceptions, Europe’s utilities pledged that they would stop investing in new coal plants after 2020.

The Guardian declared it ‘the end of coal’ in Europe, and the story even found its way into the US press.

But it’s more complicated than that.

There is absolutely a sea-change against coal in Europe, and this announcement is a big symbolic step, but let’s dive into the caveats and qualifiers before we get too carried away.

Pipeline

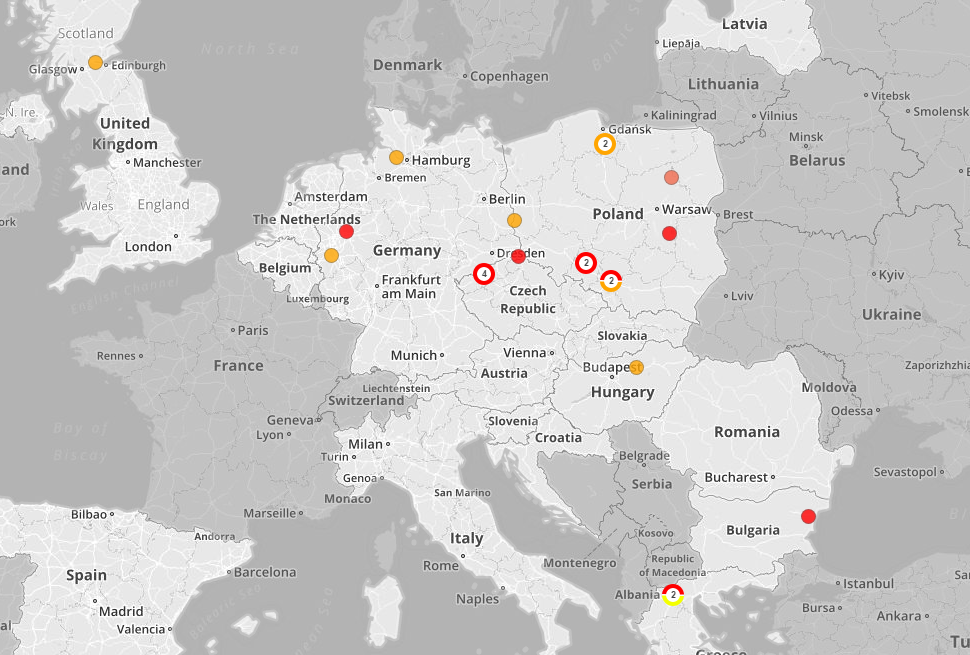

The CoalSwarm plant tracker says there are currently 22 new coal units in the pipeline in Europe, some of which are likely to be built well into the 2020s.

These projects will go ahead as planned, Eurelectric confirmed to Unearthed.

That includes 4 coal units under construction in the Czech Republic, 2 units currently at the pre-permit stage in Germany, and 1 in Hungary that’s nearly a decade away from being finished.

Utilities can also announce new coal projects in the next three years to be built after the 2020 threshold, though Eurelectric stressed that its the companies is represents are “setting a new direction.”

In addition, the whole ‘no new coal investment’ pledge does no apply to projects outside of the EU.

Poland and Greece

Look, it’s great that most of Europe is going to stop greenlighting new coal projects in a few years time, but the countries that refuse to do that are the ones that really matter.

Poland and Greece – two countries committed to coal and with a bunch of projects in the pipeline – would not sign on to Eurelectric’s statement.

On its own, the 10GW in Poland’s pipeline represents well over half of the planned 16.8GW of new coal capacity in Europe.

Not only will Poland build those 8 new units, and Greece go ahead with its 2 coal power stations, but both countries reserve the right to approve, permit and build new units in the years after.

Any ‘no new coal’ agreement without them is seriously lacking, since they’re the main places you’d expect new coal plants to crop up.

Poland, for instance, coal’s advocate on the continent, is challenging EU air pollution laws for coal plants and finagling EU competition rules to bailout its coal miners.

Old coal

Outside of Poland, the thrust of Europe’s coal conundrum isn’t over new build — it’s the pain of closing old plants and mines.

In 2015, for instance, the German government’s attempts to introduce a climate tax on heavy industry was met with massive resistance from utilities and unions.

In the end, Merkel created a ‘lignite reserve’ that pays coal power plants more than €200 million a year for staying idle in case of emergency.

Here CAN Europe has produced a map highlighting the extent of state support for Europe’s coal sector.

And here’s a handy one from Climate Analytics, produced as part of an important study showing that the EU must cancel all coal projects in the pipeline and close all existing coal plants by 2031 in order to achieve its Paris Agreement emissions target.

One way that the EU has tried to push coal to get out or clean up is through pollution standards, such as the IED or BREF.

But, according to a Greenpeace/Unearthed investigation, Eurelectric and the utilities they represent were deeply embedded in the process of shaping the BREF coal pollution standards — and weakened them.

At the behind-closed-doors negotiations, Spain’s environment ministry and Ireland’s EPA argued for weaker emission limits using statements virtually identical to Eurelectric’s.

German and British delegates made anti-regulation arguments eerily similar to those voiced by Eurelectric.

Beyond coal

That said, things *are* moving forward on the coal front.

Last week’s statement’s effectively captures the current state-of-affairs, in which coal is no longer an attractive investment nor compatible with already-agreed climate deals.

Coal plants are closing, running at vastly reduced capacity, or failing to materialise in the first place.

The Eurelectric statement, however, doesn’t really mean that much in real terms; it’s riddled with loopholes, doesn’t include the continent’s coal giant, and doesn’t address the old coal dilemma.

But it’s something, I guess.

Note: Map says UK power station Drax has 2.6GW coal capacity, but it’s now 1.9GW after latest biomass conversion