UK tries to hamper EU citizens selling their own renewable energy

Leaked documents show British government attempts to weaken aspects of the proposed Renewable Energy Directive

As Brexit looms, the British government has been pushing to weaken EU measures that would help European citizens sell renewable energy that they generate themselves, according to leaked documents obtained by Unearthed.

Analysis of UK comments on the provisions for so-called ‘energy citizens’ – which are set out in proposals for a revised EU Renewable Energy Directive – reveals attempts to curb prospects for households selling excess electricity generated from their own solar panels.

The UK delegation’s suggestions include introducing limits on households’ ability to share power generated by community renewable energy projects and enabling charges to be levied on homes that seek to sell their electricity to the grid.

If implemented, the UK’s proposals would “restrict the most transformational element of the clean energy package” and “significantly limit the ability for all citizens to engage in the energy transition,” according to Manon Dufour, an analyst at environmental think-tank E3G.

The UK is far from alone among member states in resisting the push towards decentralised, community energy in the EU, but its approach may nevertheless raise eyebrows given its plans to imminently exit the union.

The news comes just months after Unearthed revealed UK lobbying efforts to weaken the EU’s climate targets on the day it triggered Article 50 and began the countdown to Brexit.

A spokesperson for the Department of Business Energy and Industrial Strategy (Beis) said: “The UK has consistently supported collaboration with our European partners to reduce emissions and has been a leading advocate of strong environmental ambition.”

Documents

The Renewable Energy Directive – which has just cleared the European Parliament’s energy committee, and will be negotiated by the Parliament, Commission and Council over the coming months – sets out the EU’s target share of energy from renewable sources by 2030. The energy committee is currently proposing 35%.

As it stands right now, after the Parliament vote, the directive would also enshrine the right of EU citizens to generate and sell renewable energy into the grid, a method that could produce nearly half of the continent’s power by the middle of the century, according to a recent study.

It’s here where the directive has met with resistance from the British delegation — which is formally part of the Department for Exiting the European Union.

“The approach the UK, and other member states, [have] taken,” according to Josh Roberts from REScoop, the European federation of renewable energy cooperatives, “is on the one hand, to narrow the scope of what may be considered generation as much as possible, while on the other hand, to water down the text on actual provisions so that they have maximum flexibility in deciding how to implement EU legislation.”

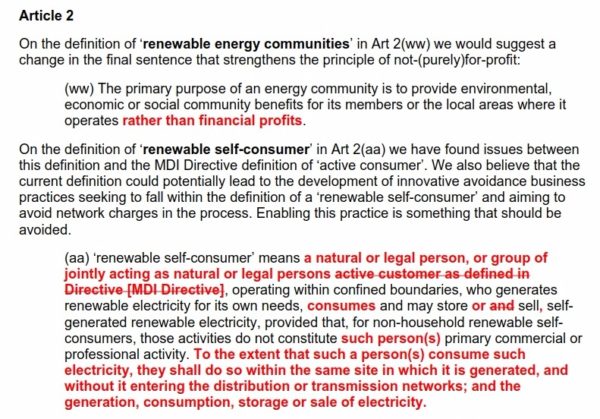

One of the UK’s proposed language changes (for Article 2 of the directive) could effectively lead to the ban of something called ‘virtual net metering’ which would help Europeans who are unable to put panels up on their own roofs to share the financial benefit from shared solar schemes (for instance renters, if their landlord had a solar array on the roof).

The UK suggests defining ‘renewable self consumers’, more commonly called prosumers, only as those who use the power “within the same site in which it is generated” and do not enter it into the grid.

“The problem,” Roberts explained, “is that, particularly for household consumers, in order to have a business case you need to be able to export excess electricity to the grid for a fair remuneration, because nine times out of ten you will not use all of the electricity produced yourself.”

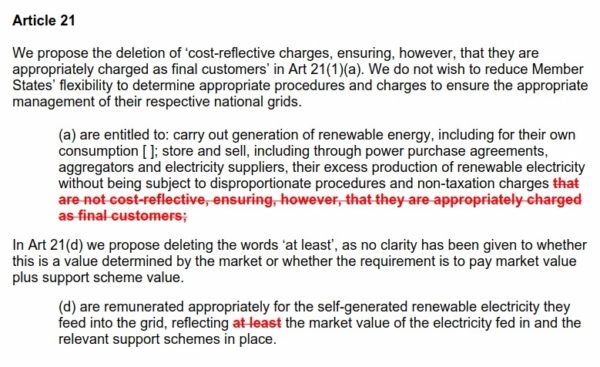

The UK also recommends (on Article 21) removing restrictions on the charges member states can levy on households seeking to sell their self-generated renewable power, deleting language that would prevent fees “that are not cost-reflective”.

And it pushes to remove a safeguard (in Article 21) on the price offered to households for their excess electricity, thereby allowing them to receive even less than the wholesale value.

Why would the UK take this position? “Self-consumption, demand response, storage, electric vehicles, aggregation, these are all incredibly disruptive to the existing order of the centralised energy system,” Roberts suggested.

He added: “We’ve mostly seen a negative line being pushed by energy companies that face competition from consumers producing their own renewable energy, distribution network operators [that] want to protect their old way of doing things, and regulators that largely listen to the energy companies and network operators.”

The UK’s proposals on virtual net metering have not yet been adopted into the text of the directive being debated by European governments. However, its revisions to the article concerning charges for ‘energy citizens’ have been taken up.

And there are a few months still for the UK’s lobbying efforts to bear fruit.

“If we end up with an approach Member States are taking in the Council,” Roberts said, “we will have EU legislation that institutionalises the ability of Member States to adopt discriminatory and burdensome requirements for self-consumption.”