Inspections and pollution tests plummet as Environment Agency sheds staff

Conservation experts say cutbacks have hampered efforts to revive the country’s dirty rivers and depleted fish stocks

The number of site inspections by England’s environmental regulator has fallen by more than a third over the past four years, an Unearthed analysis has found.

Conservation experts told Unearthed the cutbacks – which have come at a time of rapid staffing cuts at the Environment Agency (EA) – had hampered efforts to revive the country’s dirty rivers and depleted fish stocks.

The EA has shed the equivalent of more than 2,500 full time jobs (20% of its workforce) since 2013. In a statement, minister for the Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) George Eustice said nearly 1,000 EA staff – all of which were in corporate services such as finance, HR and IT – have been transferred to the department since July 2016.

Separately, earlier this month Defra revealed it had poached staff from the EA to help handle the Brexit workload.

Unearthed analysis of official statistics shows that, over the same time period, the agency has sharply scaled back on key duties, including inspections of permitted industrial sites and farms, water pollution sampling, and legal actions against polluters.

Responding to Unearthed’s findings, the EA argued that over the past year it had reduced serious pollution incidents to their lowest level since 2011.

However, frontline environmental organisations claim the agency’s reduced capacity means its staff will now usually only be able to investigate the most severe pollution incidents.

Arlin Rickard, chief executive of the Rivers Trust, which helps the EA police England’s waterways, told Unearthed: “If you ring the hotline and report a pollution incident, the Environment Agency are unlikely to come and visit unless there are dead fish.”

“Local communities are having to take things into their own hands.”

His equivalent at the Angling Trust, Mark Lloyd, told Unearthed that Environment Agency staff were privately angered by the scale of the cutbacks.

“EA staff are very frustrated that they’ve had their budgets cut, and we have an increasing number of EA officers saying ‘it’s impossible we can’t do our jobs properly’ but they’re not allowed to say that publicly.”

An Environment Agency spokesman said: “Every day we successfully manage a wide range of challenges, such as protecting people and property from flooding, improving the nation’s water quality and responding to pollution incidents, to keep our communities safe across the country.

“Over the course of the past year the Environment Agency has reduced the number of serious pollution incidents to their lowest levels since 2011, responded to more than three times the usual number of incidents during this summer’s prolonged dry weather, enhanced over 2,000km of river habitats, created over 1,500 acres of new habitat for wildlife, and built flood defences to protect over 45,000 additional homes from flooding.”

The news comes after an Unearthed investigation revealed that the EA’s fellow environmental regulator, Natural England – which has also undergone significant cuts – had left almost half of England’s most important wildlife sites unmonitored for more than six years.

‘Not fit for purpose’

Last year there were nearly 5,000 fewer annual inspections of permitted sites by EA officers than in 2014, the year when the agency first started recording data in its current form.

In addition to this, there were close to 500 fewer ‘audits’ (in-depth inspections) per year, more than a hundred fewer checks of pollution monitoring equipment, and 2,000 fewer reviews of data submissions.

The fall in these ‘compliance assessments’ coincides with a fall in recorded permit breaches by the industries regulated by the EA. Last year saw nearly 5,000 fewer breaches (27%) than were recorded five years previously.

Unearthed asked the EA if the increase in compliance could partly be the result of inspectors catching fewer breaches, but the regulator did not directly respond.

It also comes as a new parliamentary report into ‘nitrate pollution’ has highlighted a similarly significant drop in the number of inspections by the Rural Payment Agency – the body responsible for paying English farm subsidies, and checking compliance with those subsidies’ environmental requirements. RPA inspections have fallen from more than 21,000 five years ago to 17,416 last year.

The report also highlighted a 40% drop since 2013 in the annual number of water pollution samples taken per year by the EA.

The Environmental Audit Committee wrote:

“We are concerned that a number of witnesses told us that the monitoring system for water quality was not fit for purpose and that figures supplied by the Environment Agency show that the numbers of samples taken, tests carried out and funding have decreased in recent years. Despite the Agency telling us that this is due to increased efficiency, we are troubled that this is occurring ahead of the UK leaving the EU and implementation of the Government’s 25 Year Environment Plan, and before the 2018 New Farming Rules for Water have fully bedded in. We think that it is imperative that good monitoring is in place to provide a baseline against which these new policies can be measured.”

Earlier this year the EA raised the charges on businesses which finance its compliance operations in a move that could lead to an increased number of permit inspections in the near term.

‘Things are getting worse’

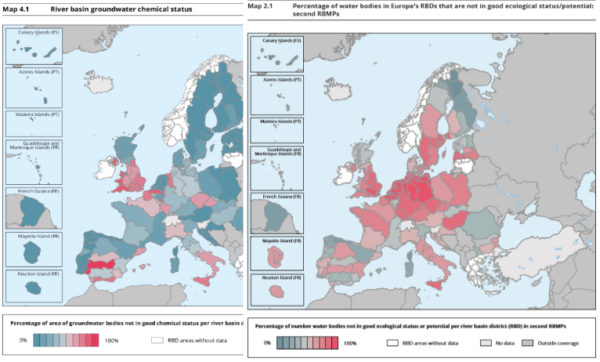

When asked about the real-world impacts of the EA’s change in approach, conservation groups point to the UK’s below-average performance in meeting the targets of the EU’s water framework directive.

Only 14% of the rivers in England are classed as having ‘good ecological status’, down from 27% in 2010. This, experts believe, is having a knock-on effect on creatures that rely on our natural world.

Salmon, for instance, is ‘at risk’ or ‘probably at risk’ in 40 of the 42 principal salmon rivers in the country, though the EA notes that the struggles of salmon are global and partly a consequence of climate change.

An EU-wide Greenpeace investigation into the water impacts of intensive farming found traces of 29 different pesticides – some of them banned – and four antibiotics in these two rivers in the southwest of England, in the catchment area of multiple types of animal farms.

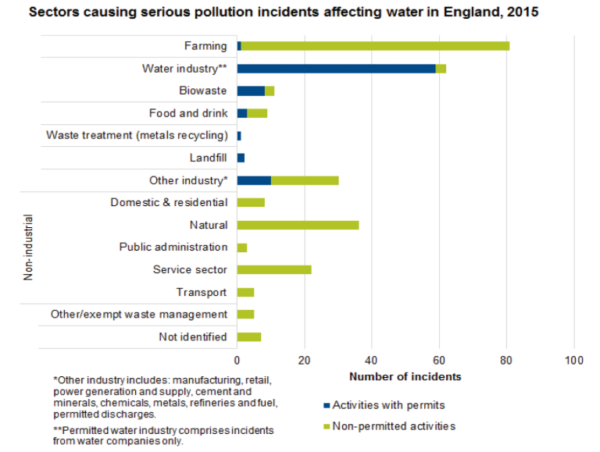

“Things are getting worse and compliance is getting worse, particularly in the agricultural sector,” according to Lloyd.

Farmers, he said, were responsible for the largest number of both serious and non-serious pollution incidents: “It’s the death of rivers by a thousand cuts. All these little trickles of pollution coming out of fields, slurry stores and farmyards add up to a giant flood of pollution which is killing our rivers slowly but surely.”

Political pressures and drastically-diminished resources have driven the EA “to take a light touch approach to regulating farmers that does not even resemble a credible threat of enforcement,” Lloyd said.

He continued: “The agency used to be able to visit farms once every 100 years, about 1% of farms in a year, which was bad enough, but the cuts have reduced their resources by half, so the average farmer can expect a visit every 200 years. Many farmers will never see the Environment Agency on their farm.”

It’s a recent development, according to Rickard. The agency were “far more active 10 years ago. They had a much bigger team of people, they were much better resourced. Although there was a reluctance to take prosecutions, you would get a visit, they would follow up and gather some evidence.”

The EA notes that 93% of the 14,000 businesses regulated by the EA showed good compliance in 2017 the number of persistently poorly managed sites was cut by 18% compared to the previous year.

Enforcements

The number of prosecutions pursued by the agency has also fallen in recent years, with 269 in 2013 dropping to fewer than 150 in 2017, and just 33 in the first half of this year.

This appears to represent a deliberate tactic, with the EA imposing far steeper fines on polluters – such as the £20m action against Thames Water in 2017 – and relying more on less-costly and less-risky civil actions called enforcement undertakings, the success of which the agency was touting just last week.

However, some conservationists fear the reduction in criminal prosecutions is sending the wrong signal to polluting industries.

“This massive decline in prosecutions for environmental crime is extremely concerning,” Matt Shardlow, chief executive of nature NGO Buglife, told Unearthed.

“I am afraid that it gives a green light to those defiling air and water cleanliness. It is essential that government acts quickly, firmly and vocally to dispel the appearance that they are turning a blind eye to people ruining our environment.”

This article was amended on 13 December. It previously said that 1,000 EA staff had been moved to DEFRA to deal with Brexit; however these staff were in fact transferred as part of a wider project to move corporate services staff from agencies to DEFRA.