China’s CO2 emissions surged in 2018 despite clean energy gains

6 things you need to know about what's happening in China

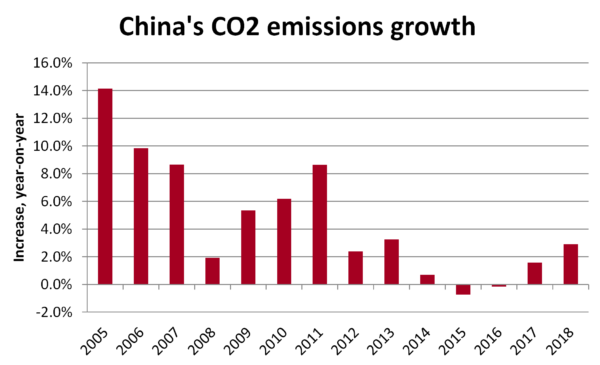

China’s CO2 emissions grew by approximately 3% last year, the largest rise since at least 2013, and all but ensuring global CO2 emissions also increased last year, according to an Unearthed analysis of newly released official data [in Chinese].

Here are 6 energy trends and takeaways from China’s latest statistical communique, including developments that promise to push emissions down in the coming years.

Swings in China’s emissions dominate global trends

China’s CO2 emissions fell from 2013 to 2016 due to a shift away from smokestack industries and construction as economic drivers, booming power generation from renewable energy and policies to tackle air pollution.

Reduction in CO2 emissions from China, the US and the UK were the primary reasons that global emissions growth stopped over this period.

However in 2016 the Chinese government kick-started another construction boom that has seen demand for steel and other construction materials surge, driving up coal use and emissions in China and pushing global emissions back to growth.

There is major uncertainty around China’s coal use numbers: production increased by 4.5% in 2018 and 3.3% in 2017, according to the government data release, and the figures also show a small increase in coal imports in both years.

Output of coal-fired power and metals, the largest users of coal, increased significantly. Yet the increase in total coal use was reported at only 1% in 2018 and 0.4% in 2017. It’s likely that coal use fell more than reported until 2016 and subsequently has increased more than reported in the past two years.

But one thing is for sure: what happens next in China is crucial for global climate efforts, as well as China’s war on smog at home.

Whether the emissions increase continues into 2019 depends on several things: whether the government responds to economic woes with another round of stimulus to highly polluting smokestack industries or decides to push for economic transformation, moderating energy demand growth; whether the speed of clean energy deployment can grow to meet overall demand growth; and whether the war on smog gets back on track after setbacks this winter.

Construction boom continues to drive emissions surge

The increase in coal demand was mainly driven by the power sector, which increased by 5%. Growth in electricity demand was driven by sectors linked to China’s construction industry – iron, steel and other metals; cement; glass and construction accounted for two-thirds of growth in industrial power demand.

Volume of construction also outpaced demand for new apartments and other real estate: 22% of apartments in China are reported to be empty. Sales of apartments were stuck at 2017 levels even as the amount of new construction started increased by 20%, making this trend financially unsustainable. However, since a large number of new construction projects were started late last year, energy use for the construction materials needed to finish the buildings will likely see energy demand continue to rise in the coming years.

The big question that remains open is how much stimulus the government wants, with new lending and infrastructure project approvals jumping to unprecedented levels in January, but the central bank telling banks to moderate lending and top decision-makers swearing by a “moderate” stimulus.

Clean air goals for 2020 could mean dramatic coal cuts

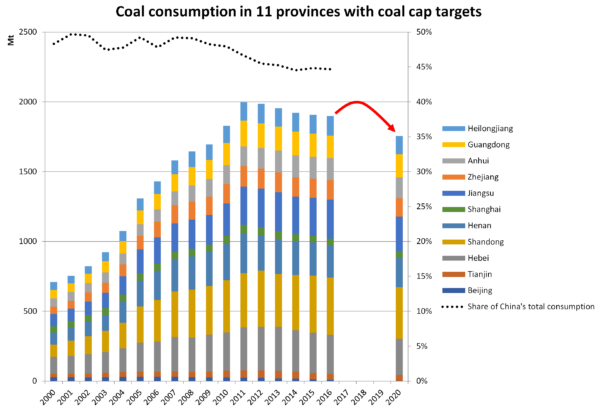

The Chinese government released a major new air quality plan – “Three-Year Action Plan for Winning the War for Blue Skies”- in 2018, with provinces releasing their own plans and targets. Based on our research, a total of 11 provinces have a “coal cap” – a target to reduce coal consumption to meet an absolute cap in 2020.

Latest province-level data on coal consumption is for 2016, when the targets would have required provinces to cut coal use by an estimated total of 140 million tonnes, or 4% of national total consumption. With coal use rebounding in the past two years, many of these provinces will need an even steeper cut in the next two years. This will be an important factor pushing demand down on the national level, too.

Coal-to-chemicals – the dirtiest industry you never heard of – is back in vogue

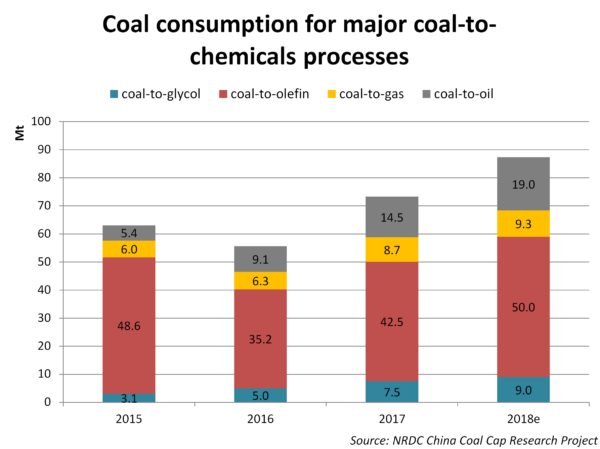

Another driver behind the coal consumption surge is coal-to-chemicals industry. Coal-to-chemical technology is a set of highly polluting processes that transform coal into oil, gas and other chemicals conventionally produced from oil, releasing even more CO2 and toxic pollutants in the process than the conventional petrochemicals industry. Yet China’s coal industry has pegged major hopes on the coal-to-chemicals industry as other sources of demand growth are expected to dry up.

Coal use in the emerging sector jumped an estimated 60% from 2016 to 2018, contributing an increase of around 0.4% in total national coal demand. Another 30% increase in coal use on the sector is expected from 2018 to 2020.

2018 saw a wave of new projects going into construction, with a single province, Sha’anxi, starting construction on 10 new coal-to-chemicals plants [in Chinese].

Clean energy surging in the shadow of coal

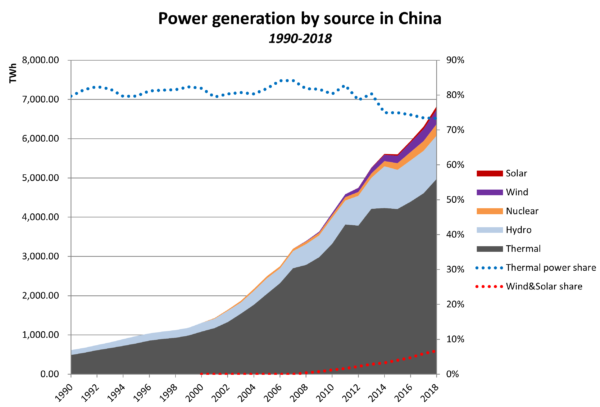

Power generation from non-fossil sources grew by 29%, with wind power generation increasing 20% and solar PV 50%. Wind and solar generated 8% of China’s power needs, up from 3% five years ago. Power generation from wind and solar in China in 2018 was equal to the total power generation of UK and the Netherlands.

The share of power generated from coal and gas fell to 70%.

However, due to the fastest growth in power demand since 2013, even this impressive clean energy growth only covered 30% of incremental power demand. To put it another way, clean energy growth would need a further tripling to match new power demand at 2018 growth rates.

New solar PV installations on the second half of the year beat expectations. There were fears that installation volumes would crash after a drastic cut to tariffs paid to solar power generators last summer, but they stayed strong, showing that solar is increasingly cost-competitive against coal in China. Early this year, China announced the first unsubsidized wind and solar projects, marking a potential inflection point for the industry.

8% may not sound like much, but with output growing at 30% per year, we ignore exponential growth at our peril.

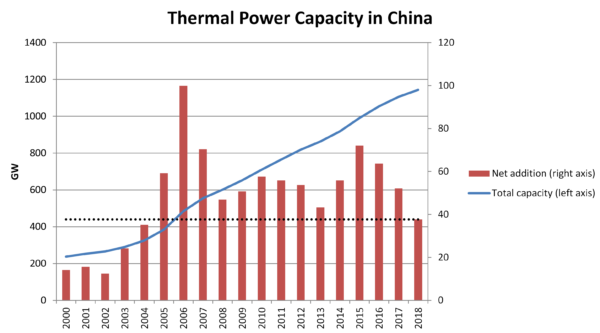

Smallest coal power capacity additions since 2004, but capacity continued to grow

Coal-fired power capacity continued to increase, with amount of new capacity added falling and amount of older plants retired increasing slightly. This is despite the alarming news that many coal-fired power projects that were ordered to halt construction in 2017 were carrying on.