A devastated section of Amazon rainforest, shot in 2018. Fires have increased significantly this year, with deforestation rates also up. Photo: Daniel Beltrá/Greenpeace

#PrayforAmazonia: why Brazil’s forest fires turned Sao Paulo’s skies black

There have been 72,843 fires across Brazil this year, a rise of 84% on the same period in 2018, as President Jair Bolsonaro's first year in office is marked by environmental destruction

#PrayforAmazonia: why Brazil’s forest fires turned Sao Paulo’s skies black

There have been 72,843 fires across Brazil this year, a rise of 84% on the same period in 2018, as President Jair Bolsonaro's first year in office is marked by environmental destruction

A devastated section of Amazon rainforest, shot in 2018. Fires have increased significantly this year, with deforestation rates also up. Photo: Daniel Beltrá/Greenpeace

Forest fires in parts of the Amazon are burning so fiercely that São Paulo – more than a thousand miles away – was plunged into an apocalyptic darkness on Monday afternoon.

A thick, nicotine-yellow haze descended on the city in the early afternoon, and by 4pm local time the sky was almost totally black. Meteorologists said the eerie darkness was partially down to wildfires burning in the rainforest.

WIldfires have become so severe in the Amazon that the state of Amazonas has declared a state of emergency, with the city of Manaus covered in smog and smoke billowing across the region. The #PrayforAmazonia tag has been trending across Brazil on social media.

Professor Márcia Akemi Yamasoe, from the Federal University of São Paulo’s department of atmospheric sciences told Unearthed the haze over the city on Monday was a result of “a combination of factors: a cold front system coupled with smoke from fires in the Amazon region, including fires from Acre, Rondônia, Mato Grosso states and also from Bolivia, north of Argentina.”

Prof Yamasoe said: “the cold front system caused the plume to deviate towards São Paulo.” This was, she said, a “common meteorological feature” during Brazil’s winter, but that a significant increase in the number of fires in the Amazon caused the strange effect in São Paulo’s sky.

President Jair Bolsonaro’s time in office has coincided with a dramatic increase in deforestation alerts. Data gathered by Brazil’s space research agency INPE, showed an estimated 2,254 sq km of the Amazon, an area almost the size of Dorset, was lost – logged or burnt – in July of this year alone, representing a 278% jump on the same month in 2018.

Deforestation can make forests more vulnerable to fires, particularly in the wet and humid Amazon, which does not burn naturally. The region’s dry season, which usually starts in late July and lasts until the end of September, can make the forest more vulnerable, but many fires in the region are started by humans.

In the states of Amazonas and Rondônia, according to data collected by the European Forest Fire Information System, fires have been burning at a much greater rate than the average of the past 15 years.

Slash and burn

Data from INPE, Brazil’s space research agency, shows that so far this year there have been 72,843 fire hot spots across Brazil, an increase of 84% compared with the same period in 2018.

More than half of these have been in the Amazon, and almost a third have been in the Cerrado, the biodiverse savannah that has lost vast swathes to soy fields over the past decade.

Prof Yamasoe said the majority of these fires will have been set deliberately by people, to clear land to grow crops and graze animals.

“In the tropical rainforest, first the farmers have to cut the trees and wait up to two months to allow enough time to dry the vegetation.”

Farmers around the world use slash and burn techniques to clear forest and the same technique is used in the Amazon, even though the practise is banned in many Amazon states during the dry season. Fires have also reportedly been used as a tactic to drive Indigenous communities from their land in Brazil.

According to INPE, Mato Grosso – now Brazil’s soy powerhouse, its name literally translates as “thick forest” – had the most fires this year, 13,682, up 87% on the same period last year. In Pará, forest fires were up 199% on last year, with 9,487 fires burning, while a spike of 146% has seen 7,003 fires in Amazonas. Rondônia has had 5,533 recorded outbreaks of fire, compared to 1,906 last year – up 190%.

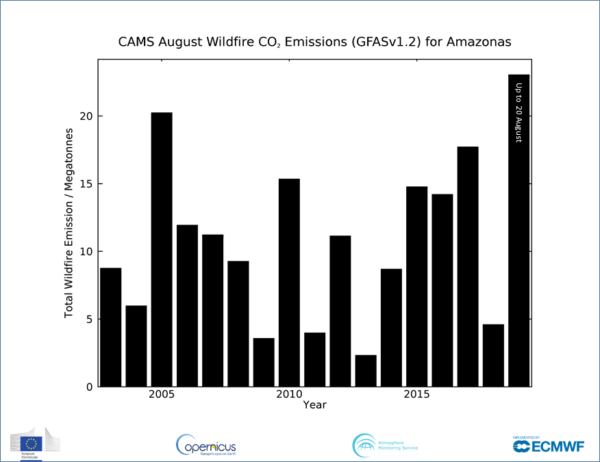

Meanwhile, data from the EU’s Copernicus earth observation system showed that CO2 emissions from wildfires across the Brazillian Amazon this August were at their highest level for the period since 2010. In the state of Amazonas, wildfire CO2 emissions are already higher than in any August since the Copernicus dataset began in 2003.

As fires spread and multiply, more trees are felled, creating a vicious cycle. When the rainforest’s protective canopy is lost, the forest floor is exposed to intense tropical sun, increasing the risk of more fires.

In turn, smoke hanging in the atmosphere can suppress rainfall, while trees help water condense and produce more rain so with fewer trees, the effect on the ecosystem and climate at large is long-lasting and can be severe.

The exact cause of each fire is difficult to establish.

However, they come at a time when the agencies responsible for monitoring Brazil’s forests are weakened and under huge political pressure. Ricardo Galvão, the former director of the INPE, was ousted from his job earlier this month after President Bolsonaro questioned the accuracy of last month’s devastating deforestation figures.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s main environmental agency, Ibama, tasked with investigating and fining environmental crimes including setting fires, has seen most of its state officials sacked and not replaced.All but four of its state enforcement bodies are currently leaderless.

Paulo Moutinho, senior scientist at the Amazon Environmental Research Unit (IPAM) which monitors deforestation and fires in the Amazon told Unearthed: “We’re in a situation that is getting worse every year. We have a government that is not environmentally friendly and is emboldening illegal loggers.”