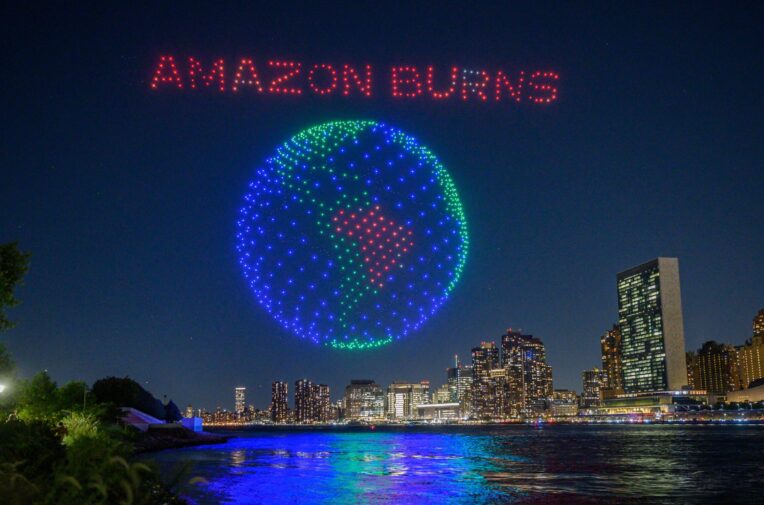

A drones display highlights the issue of Amazon deforestation during the UN General Assembly last month. Photo: Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images

Offsetting projects with high forest loss still on the market

New investigation sparks calls for greater transparency in forestry offsets and raises questions over project monitoring

Offsetting projects with high forest loss still on the market

New investigation sparks calls for greater transparency in forestry offsets and raises questions over project monitoring

A drones display highlights the issue of Amazon deforestation during the UN General Assembly last month. Photo: Ed Jones/AFP via Getty Images

The Tumring project, in central Cambodia, is supposed to protect 68,000 hectares of rainforest, an area more than ten times the size of Manhattan, in one of the country’s most important biodiversity hotspots.

Bordering the Prey Lang wildlife sanctuary — home to Asian elephants, gibbons, and dozens of other threatened species — Tumring is designed to act as a corridor for endangered wildlife including clouded leopards and sun bears. It has been hailed by the Cambodian government, which runs it, as hugely successful.

Since 2015, when the project was set up with support from the Korean forests agency, Cambodia’s government has offered companies the chance to offset their emissions by buying carbon credits that fund Tumring’s conservation efforts. The Korean and Cambodian governments have also said that credits from the project will go towards helping Korea meet its national emissions targets under the Paris climate deal.

Tumring’s offsets are overseen by Verra, the world’s largest offsetting certifier, and has sold 6,515 credits to the Texas oil company Marathon.

Now an investigation by Unearthed with Climate Home into how Verra-certified offsetting projects verify and track forest loss has found that Tumring is experiencing dramatic deforestation, which is largely undeclared in official monitoring reports.

The investigation found that Tumring appears to have lost more than a fifth of all trees in the project area, while forest loss was four times higher than recorded in official monitoring reports between 2015 and 2019.

This investigation has highlighted discrepancies between the forest loss reported by projects in Brazil and Cambodia and what can be independently verified using satellite analysis. This raises the possibility that companies could be buying carbon credits for emissions that are not being properly “cancelled out”, as the offsetting industry promises.

The global carbon market is expected to grow significantly in the coming years. A McKinsey analysis from 2021 predicts that the market for carbon credits could be worth over $50 billion in 2030. However, the offsetting market shrank by 4% in 2022, with analysts stating that concerns over a lack of quality control on projects meant buyers were reluctant to purchase credits.

Unearthed and Climate Home looked at offsetting projects in Cambodia and Brazil after a source raised concerns about apparent discrepancies between what the projects were declaring in their monitoring reports, and what could be seen through satellite images.

The team compared the projects’ filings with data developed by the University of Maryland and made available on the Global Forest Watch online platform. To check their findings they also used a second source of satellite data, Forest Observations (Forobs), which was developed by the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre to look at forest loss and degradation in tropical moist forests. This showed a similar trend to what was recorded in data available from Global Forest Watch, though forest loss numbers from the Forobs data were consistently higher.

Higher forest loss

A satellite analysis using the Global Forest Watch platform, identified 14,000 hectares (140 square km) of deforestation in the Tumring project area, between 2015 and 2019. The project’s own documents, for the same period, identified 3,450 hectares of forest loss.

The discrepancy between Tumring’s self-reported forest loss and the data available on the Global Forest Watch platform may lie in the way the project monitors deforestation.

The Tumring project’s official filings use national land cover data produced by Cambodia’s environment ministry. This data is not available publicly, making it difficult to check, and it has a low tree cover threshold. This means an area needs as little as 10% tree cover to be counted as forested. This means that an area could be 90% deforested and still be reported as intact in the project’s official documentation.

The Tumring project has sold 6,800 credits, the vast majority to Texas oil firm Marathon, with tens of thousands more available to companies to buy.

The Korean government advised on and helped fund the development of the Tumring project. Both the Korean and Cambodian governments have stated that a portion of the credits generated by the Tumring project will be shared between the governments and be used to meet Nationally Determined Contributions of the two countries, under the terms of the Paris Climate Agreement, with the remaining credits sold on the voluntary market.

The Korean government told Unearthed and Climate Home that only credits from 2021 onwards would be used to offset national emissions.

Wildlife Works, a company that develops REDD schemes around the world, worked as a technical consultant for project validation and verification but said it no longer had any connection to Tumring and that questions should be directed to the Cambodian government. The Cambodian government failed to respond to requests for comment.

Sylvera, an offsetting ratings agency that checks offsetting projects using satellite imagery and machine learning, has conducted its own analysis of Tumring. Its 2022 report The State of Carbon Credits noted that the majority of Sylvera’s D-rated projects, of which Tumring is one, “grossly under-reported the deforestation in the project area and have exceeded the baseline emissions.”

Samuel Gill, Sylvera co-founder and president, told Unearthed and Climate Home: “The technologies to largely resolve issues like underreporting or overcrediting already exist and are being deployed.” He added: “These improvements take time to filter through the system and in the next few years we should see considerable uplift in project quality as a result.”

Another Cambodian project the team looked at, Keo Seima, showed a far closer correlation between the project monitoring filings and satellite analysis, with the official data showing slightly higher forest loss than was picked up by Global Forest Watch data.

Calls for greater transparency

Monitoring reports are a vital way for buyers of credits to check what progress projects are making, but they can be difficult for the public to understand and evaluate, as there is no standardised way to monitor projects and some of the tools used to evaluate schemes are not publicly available.

The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market, an independent governance body for the industry, lists transparency as one of the 10 core principles of robust carbon credits, urging offsetting projects to make public information they use to assess the social and environmental impacts of their schemes, including spreadsheets recording forest loss and details of methodologies, so “non-specialised audiences” can better assess a project’s climate impact.

Gilles Dufrasne, from Carbon Market Watch, told Unearthed the Integrity Council is acting because “current practice on the market simply isn’t up to standard and this lack of transparency needs to be plugged. More credible, and transparent, use of forest monitoring data is part of this.”

Verra told Unearthed and Climate Home it “works directly with Validation and Verification Bodies, the project auditors who provide third-party oversight to all projects submitted to the Verra Registry, to ensure high quality standards and processes that bring credibility and oversight.” Verra added that it “is committed to refining and improving its methodologies based on the best available science and data.”

In the Amazon

The Rio Preto-Jacundá project was designed to protect over 94,000 hectares of the Brazilian Amazon in the state of Rondônia. The project has sold more than a million credits, with buyers including German utility company Entega, Bank of Santander’s Brazilian arm, and Brazilian financial services giant Banco Bradesco.

An analysis using the Global Forest Watch tool found that deforestation appears to be increasing within the project area. Official monitoring reports lodged between the project’s launch in 2012 and 2020, when the most recent report was filed, recorded 5,900 hectares of forest loss, with a sharp increase from 2016. Unearthed and Climate Home’s analysis using Global Forest Watch data found 8,200 hectares over the same period, again with a steep rise from 2016.

The scheme’s own ‘without project’ scenario, designed to show what would happen if the scheme didn’t exist, predicted 9,900 hectares of loss in the same period, raising questions about how effectively the scheme is conserving forest.

Sylvera, the independent ratings agency, has placed the Rio Preto project “on watch”, after noting increasing deforestation within the project area.

Biofílica Ambipar, which runs the Rio Preto scheme, said it “works continuously to monitor, identify and report any illegal activity to the Brazilian public environmental authorities”.

The company told Unearthed it monitors the offsetting project using PRODES, a system created by Brazil’s national space research institute. “PRODES is also the system used by the Brazilian government for official deforestation annual reports and includes double checking deforestation rates through human classification of images,” a Biofílica Ambipar spokesperson said. The spokesperson argued that the Global Forest Watch system is “not as accurate in classifying deforestation.”

PRODES is designed to detect large-scale change of primary forest, but it can miss smaller changes. The system uses satellite images that only detect clearcut logging of more than 6.25 hectares – an area equivalent to nearly nine football pitches – missing smaller-scale forest loss. The University of Maryland data, made available on the Global Forest Watch platform, captures loss as small as 0.1 hectares, while also picking up forest degradation, and loss from forest fires, as noted in this blog explaining why the two datasets recorded different levels of forest loss in the Brazilian Amazon in 2017.

Another Biofílica Ambipar project was cancelled last year after part of it was deforested by the landowner. The Maísa project had sold over 500,000 of credits, with buyers including steel giant ArcelorMittal, which purchased 26,600 credits in 2021 and 2022 and Uber, which has bought 4,000 credits, through a third party broker, since the project was terminated in September last year to offset emissions from its Latin American division. In total, over 38,000 credits from the Maísa project have been retired since its cancellation.

Uber said it “only invests in projects certified, traceable, and auditable by Verra, the United Nations, Gold Standard, and Climate Action Reserve [other verifying bodies for offsetting schemes] after a thorough investigation”.

Biofílica told Unearthed and Climate Home that the company had made it a policy “stop selling credits from the Maísa project” as soon as it became aware of the logging, which was legal. It added that “the project is currently in the process of being terminated and audited in line with Verra procedures.”

Asked what would happen to credits in the project that are still available on the market through third-party sellers, Biofílica’s spokesperson said: “It is important to highlight that the credits that are still being sold by traders and brokers refer to credits verified in previous years when there was still no legal deforestation scenario in the area; that is, they were audited and verified credits.”

When asked what happens to credits in projects that are cancelled, a Verra spokesperson explained that projects must place a percentage of their credits into a “buffer pool”. This can be “drawn on in the case of a loss event” such as logging or forest fires.

Biofílica’s spokesperson said that what happened with the Maísa project highlighted how carbon offsetting programmes based on avoiding deforestation, known as REDD projects, can struggle to compete with the economic opportunities offered by agricultural production in the Amazon. They said: “Maísa shows the reality of the Amazon region and illustrates the difficulties that all actors interested in conservation face in making carbon projects financially viable.”