Comment: A history of screw-ups – and its own plans – raise doubts about the ability of Shell to safely drill in the Arctic

The US Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) has conditionally approved Shell’s Exploration Plan (EP), putting into motion the largest — and dirtiest — oil exploration campaign ever carried out in the US Arctic. The plan involves big increases in water discharges, air pollution, ship activity, and harassment of protected marine mammals.

And that’s if nothing goes wrong.

Shell’s plan calls for two drilling rigs working close to one another in the Chukchi Sea. The two rigs are headed to the Port of Seattle, where Shell has faced fierce opposition by everyone from the Mayor to a flotilla of ‘kayaktivists.’

The rigs will be supported by a fleet of aircraft and support vessels, including tugs, oil spill response barges and icebreakers.

“History of screw-ups”

The first drilling rig is the Noble Discoverer, which in 2012 suffered through a long string of violations, screw-ups and near mishaps during Shell’s last attempt at Arctic drilling. The Discoverer nearly ran aground in an Alaskan harbor, and was later found to have violated numerous safety and environmental regulations, leading to eight felony convictions and a $12 million fine for Shell’s contractor, Noble.

Some of those violations concerned a non-functioning oily waste separator, designed to prevent discharge of pollution into the ocean. Surprisingly, a recent US Coast Guard inspection found the equipment still not functioning – though it was eventually fixed.

The second rig is the Polar Pioneer (shown at the top), which replaces Shell’s previous rig, the Kulluk (shown below), which was destroyed after running aground in a winter storm in late 2012.

This history of accidents raises serious questions about the ability of Shell — or any oil company — to safely drill in the Arctic.

A major spill would be catastrophic for an Arctic marine ecosystem that is already reeling from rapid climate change. A spill would lead to both an initial wave of animal deaths as well as effects that could linger for decades.

“Rosy assumptions” for spill scenario

Far from being a remote possibility, BOEM itself has estimated that there is a 75% chance of a large oil spill during the 77-year oil development window.

Unfortunately, Shell’s EP and associated oil spill response plan (OSRP) do little to assuage these concerns. Recent studies have shown that Arctic wind, wave, ice and visibility conditions would make it impossible to deploy oil spill response tactics for a significant fraction of the time, even in summer months.

Rather than addressing this objection head-on, Shell relies on several rosy assumptions in its plan. For example, the OSRP assumes that 95% of the oil from a major oil spill would be captured by “offshore recovery efforts” before it approaches the Alaskan coastline. Typical recovery rates, even in less challenging environments, are rarely higher than 20%. Shell also assumes that it will have six days to move shoreline resources into position, whereas BOEM estimates that oil could reach land as early as three days.

The scenario that should keep government regulators up at night is a well blowout late in the drilling season, where a relief well must be drilled to stop the spill before the winter ice freeze-up occurs.

Shell’s plan includes a discussion of such a scenario, but likewise neglects to consider what might happen if freeze-up happens sooner, or if the relief well takes longer, than estimated. In all of these cases Shell fails to analyze the robustness of their plans to changes in assumptions, making it difficult to truly assess the risks involved.

Pollution plans

But even apart from a worst-case scenario, if BOEM approves the exploration plan, the general increase in industrial activity will lead to greater water, air and acoustic pollution in the Chukchi.

Although Shell had previously agreed to a “zero discharge” policy when drilling in the Beaufort Sea in 2012, their current plan calls for the discharge of thousands of barrels of drilling muds, cuttings and other waste directly into the ocean. These wastes can contain heavy metals and toxins and can damage benthic communities which form important links in the Arctic marine food web. The Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission recently criticized Shell for this policy.

Shell clearly has the technical ability to implement a zero discharge policy and it could be required by BOEM as a condition of approving the exploration plan.

The exploration plan estimates that the total air pollution emitted by this fleet will be greater than in 2012, when Shell’s fleet was found to be in violation of its air permit. Among the pollutants emitted by these operations are nitrogen oxides, which has been linked to respiratory problems, and fine particulate matter, which increases the risk of premature death among people with existing health problems.

Black carbon, which is a component of particulate matter, also increases the rate of local warming by decreasing the amount of sunlight that is reflected by snow or ice.

In addition, a recent Nature study confirmed that Arctic oil reserves are unburnable if we are to have a chance at limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celcius.

Impact on Arctic species

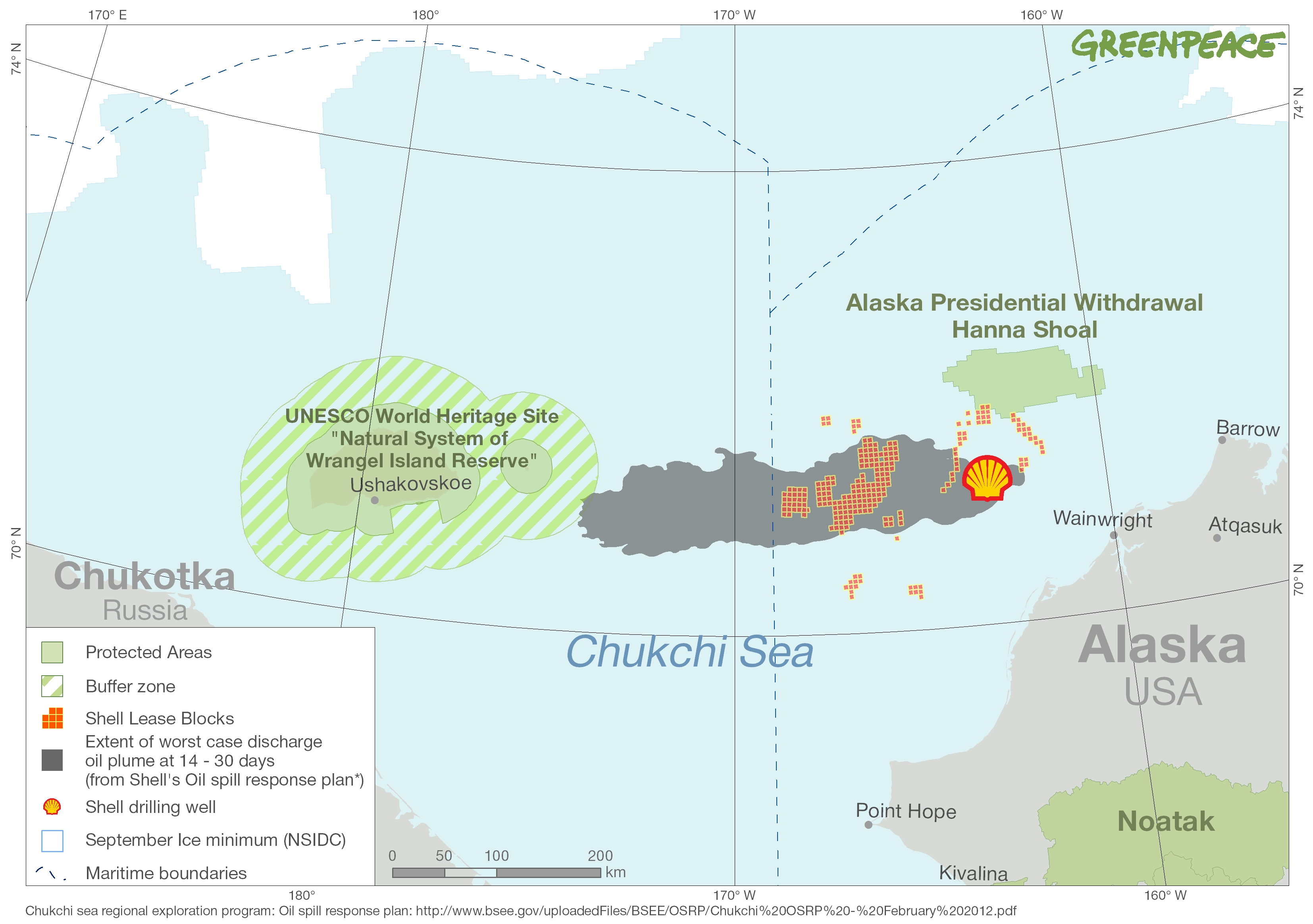

Shell’s drill sites lie directly adjacent to Hanna Shoal, a critical walrus habitat and biodiversity hotspot. Shell’s own oil spill modeling shows a potential oil spill trajectory heading toward Wrangel Island, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that is prime denning habitat for polar bears and home to a large population of Pacific walrus (see map below).

Drilling activities, icebreaking and seismic testing all create loud disturbances that have the potential to harass wildlife. Whales, walruses, polar bears and other species can be harmed directly by seismic testing or may alter their feeding or migration patterns to avoid disturbances. Shell estimates that its activities will harass thousands of beluga, bowhead and gray whales — a significant fraction of the local populations.

Given that many of these populations are already listed as endangered or threatened, Shell’s activities may have an outsized impact on them.

Should Shell discover oil in the Arctic, it’s clear that the planet can’t afford to drill and burn it.

Tim Donaghy is a senior researcher at Greenpeace USA

Also Read:

- Oil price drop increases risk of offshore oil drilling disasters, expert says

- Shell’s Arctic rig in trouble over safety and environmental issues – again