How Shell’s Arctic drilling will ‘harass’ thousands of whales & seals – with potentially harmful impacts

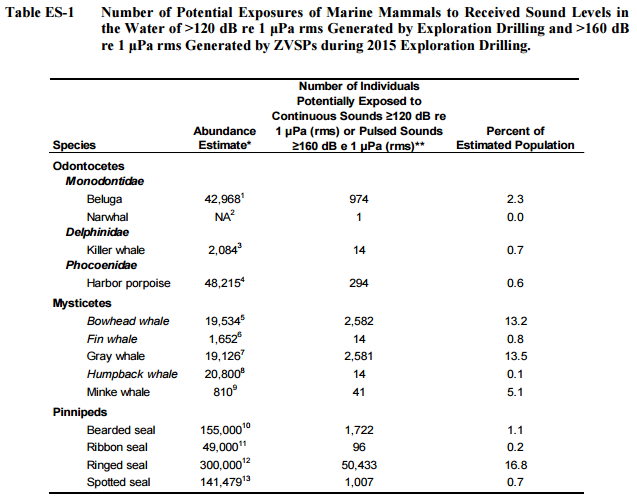

UPDATE 17/6/2015: Shell has obtained their permits to harass thousands of whales and seals from Obama’s government, according to environment newswire E&E – though the amount of marine wildlife approved for harassment are lower than in Shell’s original application. The numbers authorised for ‘take’ are: 1318 belugas, 1038 bowheads, 834 gray whales and over 25,000 seals.

Shell plans to “harass” thousands of whales and seals – including three different endangered whale species and one threatened seal species – as a by-product of its Arctic exploration, according to public documents.

The energy giant has applied for a permit to harass the marine mammals, meaning it will generate underwater noise pollution that will affect their behaviour.

The company says in the application that though its drilling and seismic testing will be heard by thousands of mammals the noise won’t have any “biologically significant” impacts.

However, Shell’s analysis is based on an out-of-date scientific understanding of the impact of noise on marine mammals, according to scientists and the agency to which it has applied for a permit.

More recent research suggests that more mammals may be affected, and the noise may have unpredictable – potentially harmful – impacts on the behaviour of the animals and the Indigenous communities which rely on them for food.

Christopher Krenz, a scientist and Arctic campaign manager with Oceana told the Guardian whales’ hearing could be damaged, which could have lethal consequences for whale calves.

Shell hasn’t responded to requests for comment from Unearthed.

Endangered species

Shell’s own analysis estimates it will “harass” around 13% of the bowhead and gray whale populations, and 17% of the ringed seal populations, representing thousands of animals.

Bowhead, humpback and fin whales are listed as endangered, while ringed seals are considered threatened.

The permit to harass the animals is being currently being considered by the US’ National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS).

The agency is in the middle of updating its acoustic thresholds to reflect newer science – though this may not be completed before the Shell application is approved.

The scale of the planned harassment has led research organisations and civil society groups to argue that if the NMFS approves the permit, it could be breaking the law.

“Negligible” impacts?

The groups – including Northern Alaska Environmental Center, Ocean Conservation Research and Environmental Investigation Agency – claim that Shell’s proposals for mammal harassment in the Chukchi Sea contravene the US Marine Mammal Protection Act, which states that impacts should only affect a small number of the creatures and should be negligible.

Environmental groups also claim the NMFS can’t approve individual projects like Shell’s, under the US National Environmental Protection Act, until it finishes its analysis of the overall impacts of drilling in the region.

Shell says in its permit application that marine mammals could temporarily be affected by underwater noise from its equipment, but they say the impacts would not be “biologically significant”. They say there might be temporary changes in behaviour but it’s “extremely unlikely” the proposed activities will result in stranding or death.

“We don’t know yet if, over long timescales, this elevation in background noise can lead to the species having trouble hearing their conspecifics’ calls or detecting biologically significant cues from their environment.”

Melania Guerra, marine researcher

Harm to Arctic whales, seals calculated using old science

In Shell’s permit application it considers an animal to be impacted or “taken” if it could be affected by continuous noise – from drilling and from icebreakers – of over or equal to 120 decibels or pulsed sounds – from vertical seismic testing or pile driving – of over or equal to 160 decibels.

But a raft of newer scientific research has shown that certain marine mammals are impacted by noises well below the threshold.

New recommendations published in 2007 in the journal Aquatic Mammals suggest marine mammals shouldn’t all be treated the same in terms of their hearing sensitivity, but should be grouped according to their sensitivity to sound frequencies, the frequencies the animals use, and behavioural effects.

The same review also explains that migrating bowhead whales were significantly affected by pulsed sounds of 120 dB.

Meanwhile, both bowhead and beluga whales have been observed responding to drillship noise at a lower threshold than 120dB, according to a 2011 US Geological Survey report.

Effects of pulsed sounds not yet known

Marine scientists have also recently discovered that pulsed or ‘impulsive’ sounds also have the potential to cause direct or indirect harm to marine mammals – as well as continuous noises.

“One example of indirect harm is what is called “masking”: the impulsive sounds reverberate in the shallow water like echoes in a room and elevate the ambient noise,” Melania Guerra, an ocean acoustics researcher at the University of Washington told Unearthed.

“We don’t know yet if, over long timescales, this elevation in background noise can lead to the species having trouble hearing their conspecifics’ calls or detecting biologically significant cues from their environment.”

Guerra, who is working specifically on measuring ambient noise in the Arctic and its potential impacts on the acoustic habitat of marine mammals, added “This could be a big deal for the species, but the effect would only become evident chronically, over timescales of many years or decades.”

Data & research gap risky for sea creatures and humans

There’s more we don’t know. Scientific research on the cumulative effects of underwater industrial noise pollution – rather than individual activities – are in their very early days. Researchers are only just developing tools to address this.

There is also a data gap on the baseline size of Arctic marine mammal populations. A recent literature review published in Conservation Biology found for most Arctic marine mammal subpopulations, we don’t have accurate abundance numbers, or know if they’re stable, declining or increasing.

“Given that many of them are harvested for subsistence by Native Arctic communities, incidental takes on a population that is unknowingly decreasing could mean not just a huge biodiversity loss, but could affect peoples’ cultural and social survival,” Guerra said.

Can impacts on whales be avoided?

In Shell’s application, it says there will be “negligible effects” on the populations of the animals from its noisy activities in the Chukchi Sea, and therefore it won’t be a problem for subsistence hunters that can’t be mitigated – even though a sizable proportion of some species stocks could be affected.

Shell’s drill site lies near the migration paths of the bowhead and beluga whales, skirts the edge of the grey whale habitat, and is right next to Hanna Shoal, a critical walrus habitat and biodiversity hotspot. Harbor porpoise, and ringed, spotted, and bearded seals are also common near the drill site.

(Illustration: Lauren Wade/TakePart)

The firm’s mitigation strategy includes monitoring the sea around their vessels, and responding by moving more slowly or not changing direction suddenly if they are near whales, or halting seismic testing, as well as instating minimum flight altitudes and consulting with subsistence advisors on Beluga whale migration.

“The difficulty lies in implementing mitigation measures for those recommendations in practice – in extreme environments, for instance, from a moving boat, under visibility conditions that could be foggy or ice covered,” Guerra told Unearthed.

Shell writes it will slow down its vessels in “inclement weather conditions” to avoid collisions.

Separately, Arctic marine mammals could also be affected by an oil spill – which there is a 75% chance of over the lifetime of oil exploration in the Chukchi Sea – and climate change may be already boosting their risk of disease.

Shell will also be submitting a permit application to harass land animals such as polar bears and walruses – but we don’t know when.

Read more:

- Interview: ‘There is no way they could ever clean it’ say Indigenous leaders on Arctic oil spill

- Factcheck: How to clean up an Arctic oil spill in four steps (and why it is unlikely

- Factcheck: Shell commissions Vice style video on how gas can stop climate change – if you are ok with up to 6 degrees warming