Q&A: Brazil’s giant new Amazon dam-building project and why it matters

A controversial dam on one of the Amazon's last free-flowing tributaries poses a threat to biodiversity and has angered indigenous groups

As it prepares to host the Olympic Games Brazil is embarking on another – much less reported – giant infrastructure project.

The Tapajós dam development is taking place well away from the gaze of visitors to the Olympic Village, deep in its inland Amazon jungle – and its legacy could be far greater.

The project, which is one of numerous planned dams, threatens large-scale deforestation, loss of biodiversity and has created conflict with local indigenous groups.

Here’s a brief Q&A on the project:

What’s going on in the Amazon?

One of the last free-flowing rivers in the Amazon, the Tapajós, is the latest target for the Brazilian government’s dam-building programme.

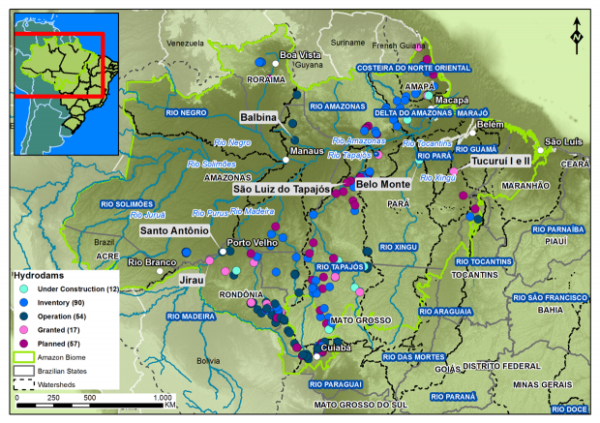

At least 40 large dams are being built or planned in the Amazon, which will require smaller dams upstream to guarantee water flow.

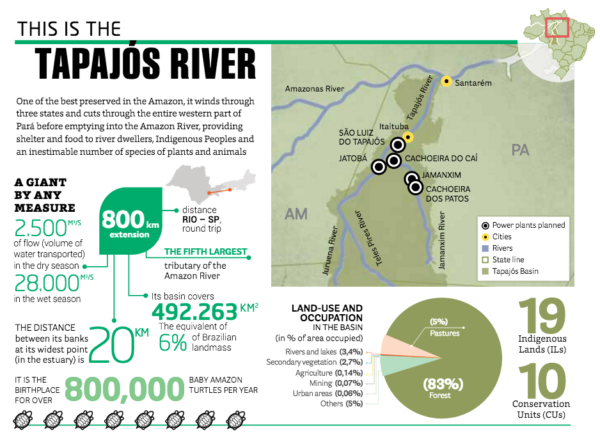

The Tapajós is the fifth-largest tributary of the Amazon River, running 800km through the state of Pará.

It supports over 14,500 Indigenous Peoples and members of river communities, and an inestimable amount of Amazon flora and fauna – some of which have never been recorded by science.

The São Luiz do Tapajós dam would be a 7.6km-long concrete wall cutting across the river, 53 metres high. Its installed capacity is 8,000MW.

Great! Hydropower is a source of clean and renewable energy, right?

Sure, hydroelectricity is conventionally known as renewable energy, because it relies on water flow to turn turbines to generate electricity – rather than burning fossil fuels which emit carbon dioxide.

However a 2014 study suggests that in the tropics – particularly rainforests – hydroelectric dams are not as climate-friendly as they seem, due to the amount of methane they release when flooded vegetation rots.

And methane is actually 34 times more powerful a global warming greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide over a 100-year period.

Dams can also turn out to be ineffective. Many parts of Brazil have recently been suffering from crippling droughts – which isn’t great for hydropower.

What will be the impact on the forest?

Technically building a dam doesn’t need to involve large-scale deforestation– but that really is a technicality.

Beyond the immediate deforestation caused by the dam, associated roads and flooded areas dams are also deforestation multipliers.

Roads – originally built as infrastructure for the dam’s construction phase – provide gateways to new areas of forest, inviting loggers, ranchers and agribusiness into the area.

The ongoing construction of the Belo Monte Dam – the third-largest dam in the world, on the Xingu River east of the Tapajós – has seen reports of huge amounts of forest burned and felled, and an increased trade in illegal timber, including purchases by the construction consortium.

So does that knock on to local ecosystems? And what’s the scale of that?

The deforestation and flooding involved in dam-building in the Amazon has irreversible impacts on biodiversity.

A recent study in Science warns that the unprecedented boom in construction of hydropower dams in the Amazon, Congo and Mekong “overestimate economic benefits and underestimate far-reaching effects on biodiversity and critically important fisheries”.

Previous dams built in the Amazon have had big impacts on wildlife. The Balbina Dam reservoir was designated a “biological nature reserve” containing 3,546 artificial islands created by flooding in the area.

The trouble is, most of these islands are not big enough to support continuing populations of animals like howler monkeys, who die in isolation on the islands due to poor swimming skills.

The Amazon is the world’s largest reserve of freshwater, with around 100,000km of rivers that are filled with nutrients – so the impacts go beyond immediate and secondary deforestation.

A new study on Amazon hydrology highlights how dams directly affect floodplain ecology, the critical habitat for many species’ lifecycles, including otters, turtles, caimans and pink dolphins.

The lack of baseline studies on many of these ecosystems – and the inability to predict how severe the impacts of damming will be – could mean many species would simply collapse.

Surely human populations in the region will benefit though?

Well. Dams also interrupt fish spawning patterns, which impacts upon river communities that depend on them for protein and income. So food security for Amazonians is under threat.

But Indigenous Peoples are hit the hardest. In the case of the São Luiz do Tapajós, the Munduruku tribe of about 12,000 people will see parts of their ancestral lands flooded – including sacred sites.

The Munduruku have lived on land along the Tapajós River for centuries, in an area called Sawré Muybu, which covers 178,173 hectares.

It is estimated that 7% of this land will be flooded. They have vowed to fight against the dam project.

Brazil’s constitution has clauses that protects Indigenous Peoples, and many areas in the Amazon are officially protected to allow native populations to live undisturbed.

However there’s been a delay in the final phase registering the Sawré Muybu land as protected, which some attribute to the plans for the dam.

But dam construction and more industry must create some jobs?

This is true – and Brazil’s struggling economy probably accounts for much of the appeal of this kind of project.

For some in Brazil the opening up of a large new part of the rainforest will ultimately bring development in the form of further roads, towns, industry and prosperity.

There are problems even here though.

The jobs that are created directly by the dams have natural time limits, leaving labourers without work once construction is finished.

Local towns often don’t have the infrastructure to cope with the influx of temporary workers.This “boomtown” effect can be devastating socially and environmentally.

The population of Altamira, the town closest to the Belo Monte Dam site, surged by almost 50% in two years – increasing the need for housing, food, and healthcare.

Basic waste disposal and sanitation weren’t installed, meaning raw sewage ran into the Xingu. Drugs, violence and prostitution are rife and the murder rate in Altamira increased by 80% in the same period.

A lot of the logging and ranching activity is often run by criminal gangs, who are at the forefront of illegal deforestation in the state of Pará.

For years the government has had trouble keeping deadly battles for land in check. Brazil has the highest murder rate of environmentalistsof anywhere in the world.

Modern slavery is also a growing concern in the region. Workers are promised well paid jobs and are bussed in from the poorest states in northern Brazil. They can then end up in debt bondage and risk being killed if they complain.

This all sounds pretty terrible. Why build these dams in the first place?

The Brazilian government has made no secret of the fact that it wants to industrialise the Amazon to provide power for Brazilians – however other theories also exist.

In 2015, the former CEO of one of Brazil’s largest construction companies, Camargo Corrêa, testified to public prosecutors that the company had paid US$9.6 million to the ruling Workers’ Party (PT) and their coalition partner PMDB in exchange for contracts to build the Belo Monte Dam.

It now looks unlikely that Belo Monte will generate enough power to even pay for itself.

Another theory is that massive electricity projects are seen as necessary to increase mining operations in the Amazon. Primary commodities – like iron, which is mined in Pará state – are a big earner for Brazil.

The Brazilian government does undertake environmental impact assessments, but these are increasingly seen as formalities for legitimising political decisions that have already been made.