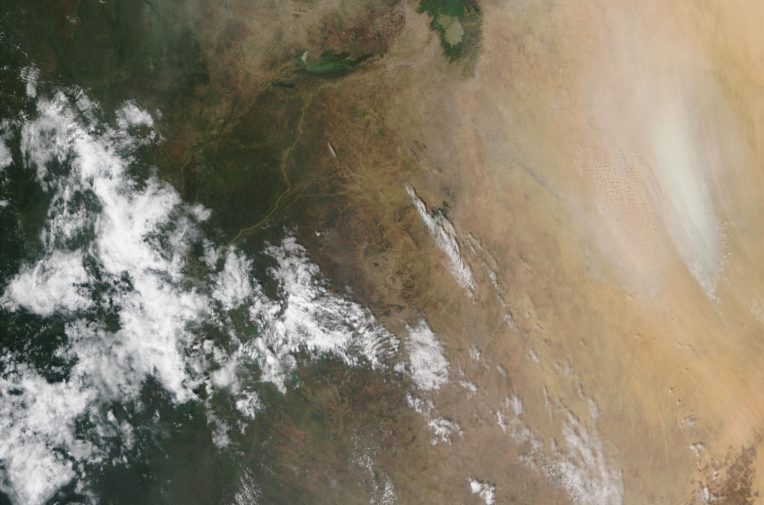

NASA satellites show a large dust storm blowing south towards Lake Chad, one of the only water sources in the area. Photo: Jeff Schmaltz/MODIS Rapid Response Team/NASA/GSFC/Getty

‘It’s a question of survival’: fighting climate change in one of the world’s poorest countries

David Naibei, 20, has set up a teaching programme in a country that is among the most vulnerable in the world to climate change

‘It’s a question of survival’: fighting climate change in one of the world’s poorest countries

David Naibei, 20, has set up a teaching programme in a country that is among the most vulnerable in the world to climate change

NASA satellites show a large dust storm blowing south towards Lake Chad, one of the only water sources in the area. Photo: Jeff Schmaltz/MODIS Rapid Response Team/NASA/GSFC/Getty

Fighting climate change in one of the hottest and poorest countries in the world was never going to be easy.

But that’s exactly the task 20 year-old David Naibei, an environmental activist from Chad has taken on. His north-central African country has been ranked as the most vulnerable in the world to climate change, due to high poverty, frequent conflicts and constant risks of droughts and floods.

“The temperature can get up to 47C,” he tells Unearthed. “People are dying because of lack of water and terrible heat. It’s hard to work, it’s hard to imagine a future for young people.”

Naibei, who has addressed the UN on climate change, educates more than 2,500 children a year with Espaces Verts du Sahel, a Chadian NGO where he has worked for five years.

The desert advances on the cities. Our beautiful Lake Chad is disappearing

He goes into schools and creates ecological clubs that can teach the children about how climate change impacts them on a daily basis and how they can live sustainably. Already he has worked with 54 schools and recently helped two schools in France launch their own clubs.

“The children are learning fast, but they’re worried because the weather is getting warmer. And they’re wondering why people are doing bad things to our planet instead of saving it. They don’t understand why we’re not using solar electricity, especially in a country as sunny as Chad.”

Chad’s president Idriss Déby has highlighted climate change as a pressing issue for his country. But despite Chad having a high potential for solar – the city of Faya-Largeau is one of the sunniest places on earth – the country relies almost exclusively on fossil fuels.

Lack of administrative structures and human resources have been cited as the reason Chad has yet to capitalise on the UNFCCC’s funding for renewable energy development.

Water and conflict

Naibei also teaches children the role the environment has to play in conflict prevention, something particularly relevant for his country.

A 2017 report by the UN on Lake Chad highlighted the “adverse effects of climate change and ecological change…on the stability of the region, including through water scarcity”.

An analysis by environmental consultancy adelphi found climate change contributed to creating conditions where terrorist groups can thrive, while at the 2015 Paris climate conference Déby went so far as to say the Lake is a “base” for Boko Haram.

“Environmental problems are real here. The desert advances on the cities. Our beautiful Lake Chad is disappearing.”

Lake Chad, which provides water to more than 68m people, has shrunk by as much as 90% in the past 50 years, due to drought and increasing withdrawals of water for irrigation.

The majority of Chad’s population relies on agriculture, and the lack of water means it is becoming harder for people to produce enough food.

“Farmers in my country are praying for rains to come. But they’re just getting drought. They don’t know how they can get water to grow food and raise animals.

“Right now there’s a conflict between those people practising agriculture and those practising livestock. Both need water to make their living, so they’re fighting. I strongly believe it will get worse. There will be a water war.”

The future

Naibei says although “everyone in Chad” believes in climate change, many do not understand what it is.

“They know the climate is changing because they are living it, every day. They know the weather is getting warmer, but they don’t understand why. I’ve seen people crying because they have no food or water, and they don’t realise it’s related to global warming.”

The reason Naibei focuses on educating children over adults is simple: “They’re going to be the future leaders.”

“They’re going to be the ones making decisions, so if they’re educated now, they’ll understand what global warming means. When they’re politicians, they’ll make better decisions for our planet.”

Naibei wants other countries to take a more proactive approach: “If all the countries in the world have environmental classes, even just at primary school level, in 10 years you will see a huge change.

“To many students we teach, success means big house and big cars. That’s what they’ve been taught from an early age. And when they grow up, when they find out that this big car is bad for the environment, do you really think, at this stage of their life, their going to give that dream of a big car up?

“But if they’d been told at primary school the car they should to aspire to is an electric one, then that’s what they would’ve bought when they became successful. It’s about changing attitudes and lifestyles.”

“It’s a question of survival. We have one planet, if we destroy it, we will just die, disappear. It’s as simple as that.”

Lucy Sherriff is a freelance journalist based in South America covering environment and gender issues through video, writing and radio