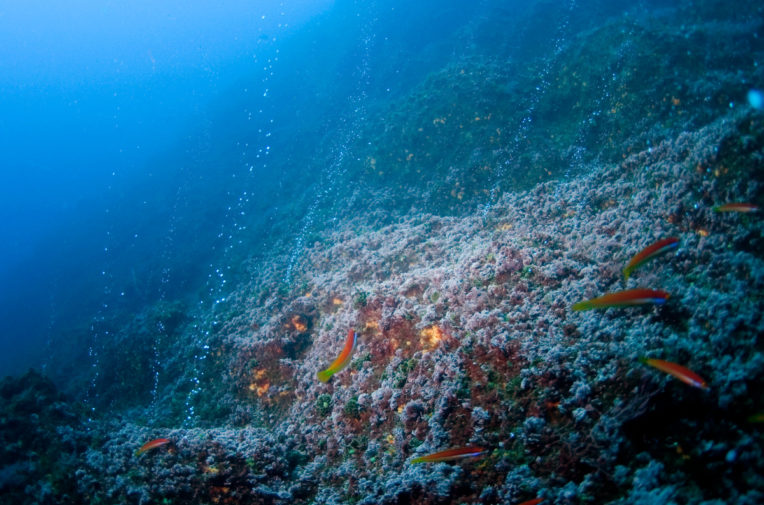

Hydrothermal vents at Dom João De Castro in the central north Atlantic Ocean (2006) Photo: Greenpeace, Gavin Newman.

UK government warned deep sea mining could cause ‘potential extinction of unique species’

The UK’s joint project with American military firm Lockheed Martin is the largest in the world but poses risks to deep sea ecosystems

UK government warned deep sea mining could cause ‘potential extinction of unique species’

The UK’s joint project with American military firm Lockheed Martin is the largest in the world but poses risks to deep sea ecosystems

Hydrothermal vents at Dom João De Castro in the central north Atlantic Ocean (2006) Photo: Greenpeace, Gavin Newman.

Deep sea mining could lead to “the potential extinction of unique species which form the first rung of the food chain,” according to a report commissioned by an arm of the British government.

‘The Subsea Mining Capability Statement’ – obtained by Unearthed using freedom of information rules – was produced by the National Subsea Research Initiative in 2017 and circulated amongst the UK government’s deep sea mining working group at key stakeholder meetings.

The British government has licenses for exploratory mining of polymetallic nodules in the Pacific Ocean as part of a joint venture with UK Seabed Resources, a subsidiary of US defence firm Lockheed Martin.

The statement’s environmental warnings echo those heard from the scientific community, many of whom fed into the UK parliament’s ‘sustainable seas’ inquiry which concluded deep sea mining “would have catastrophic impacts on the seafloor site and its inhabitants.”

The process of gathering the minerals that lie atthe bottom of the ocean – which includes cobalt, a key ingredient in the batteries that power smartphones, laptops and electric cars – by deploying massive remote controlled vehicles to hoover up mineral deposits from the seabed floor

It comes as many in the scientific community have been sounding the alarm over the risks posed by deep sea mining, though some cautioned that not enough is yet known to justify the claim about the extinction of key species in the capability statement. That, in turn, has led to calls for further research.

Kerry McCarthy, a Labour MP who sits on the Environmental Audit Committee, told Unearthed: “As the fragility of our planet and its ecosystems becomes starkly more apparent, it’s difficult to believe the Government is continuing to promote deep-sea mining in the full knowledge it could pose risks to unique species that are integral to the food chain.”

David Rennie, head of Oil and Gas at Scottish Enterprise, the government agency that commissioned the Subsea capability statement, told Unearthed: “This report was commissioned to highlight the market potential in a range of sectors such as aquaculture and marine renewables, that Scotland’s subsea capability could be appropriate for in future market activity. We regularly undertake research into markets to understand the potential these may have for Scotland’s businesses and economy.

“As yet we have not made any decisions, or progressed any activity, on how we might develop seabed mining. Other sectors such as marine renewables and aquaculture are likely to offer more immediate opportunities and any significant developments in seabed mining are likely to be some years off.”

A UK government spokesperson said: “The UK continues to press for the highest international environmental standards, including on deep sea mineral extraction. We have sponsored two exploration licences, which allows scientific marine research to fully understand the effects of deep sea mining and we will not issue a single exploitation licence without a full assessment of the environmental impact.”

Here is the industry report commissioned by the government agency Scottish Enterprise:

The distant ocean

Deep sea mining has yet to start commercially anywhere in the world, but environmental concerns are based – in part – on the scale of the projects under consideration, with the UK set to play a leading role in the industry.

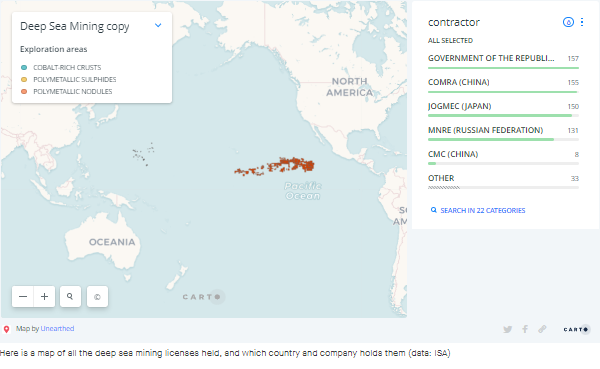

Mining exploration licenses have been distributed to 22 projects by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), the intergovernmental body responsible for regulating resource extraction in the high seas. Each of the licenses must be sponsored by a national government.

The territories licensed – spanning the polymetallic nodules south of Hawaii and the cobalt-rich crusts in the Asian Pacific region to the sulphide deposits around the Atlantic Ocean’s Lost City and even more nodules in the Indian Ocean – total an area twice the size of Ukraine.

An Unearthed analysis of ISA data shows the UK’s venture with Lockheed Martin is the single biggest project in the world, covering an expanse off Mexico larger than England itself.

The Chinese government, which holds licenses with 2 different companies, controls the most territory, with the UK government at number 2. The country is reportedly leading efforts to agree on a law allowing mining by 2020.

The United States does not hold licenses since it has not yet ratified the Law of the Sea Convention (1994) and is thus not a member of the ISA.

Environmental fears

Deep sea mining at this scale has prompted serious concerns from scientists who warn that far too little is known about the habitats it will disrupt. Many are calling for a years-long moratorium whilst research takes place.

Rachel Mills, Professor of Ocean Chemistry at the University of Southampton, told Unearthed: “We have been interested in mining deep sea floor since the 1970’s and scientists have long argued that small scale experiments should be carried out to understand the impacts of potential extraction techniques.

“What we know is that long after these experiments were conducted, the seafloor is still scarred, and devoid of the hard nodule substrate required to support the seafloor communities. What we don’t know is what impact this has on the deepest abyssal plains on the vast ocean floor.”

Though she said some scientists believe there is already requisite information to begin mining, Professor Mills called on government to “abide by the precautionary principle,” arguing that “we are a long way off from knowing how to conduct adequate and comprehensive environmental impact assessments.”

“If there’s one thing we’ve learned from mining on land it’s that you need to know about the environmental impact on different scales and over time, and we just don’t know enough yet.”

Jessica Battle, who works on ocean governance for environmental group WWF, made a similar call for an extended moratorium on deep sea mining until we better understand what impact it could have.

“Scientific understanding of the ecosystems in the deep sea is still in its infancy, so much could be destroyed before we even know what’s down there, or the benefits that these fragile ecosystems provide to the planet and humanity. We certainly do not think that the case has been made for seabed mining to progress. We urge all actors involved in consideration of this form of exploitation to hold back and allow the science and conservation of these ecosystems to catch up.”

These concerns are well-known to the officials who lead the ISA, including its secretary general Michael Lodge, who wrote in 2013 that some “ecosystems may never recover” from deep sea mining activity.